Lecture

Let us begin with the most elementary level of the structure of the language, the phonetic level. In psycholinguistics there is a special section devoted to the study of the relationship in the linguistic consciousness of sound and meaning - phonosemantics .

Almost from the first stages of the emergence of linguistic studies there are two points of view on the problem of the connection between the sound of speech and word on the one hand, and meaning on the other. According to most scholars, the sound itself does not carry meaning, the set of phonemes in different languages does not always coincide, the sound composition of different languages is different. This means that the sound image of words is conditional (conventional). In fact, the concept of a table in Russian is a combination of sounds “s-t-l”, in German it is Tisch, in English it is a table, etc. Nothing in common except for one sound [t]. It would be strange to believe that a single sound can have any meaning that, say, words, morphemes in their composition (a morpheme, for example, in Russian and Ukrainian languages has the meaning of grammatical

ska kind: she, izba, went, etc.). So the above-mentioned point of view of linguists is good, it would seem, argued. But it turns out that in the view of a famous French symbolist poet, vowel sounds have meanings ... colors:

A - black, E - white, U - green, and - bright red,

O— sky color! Here so, that neither day, nor hour,

Your hidden properties - I take the color and the eye,

You on color and smell I try, vowels!

(Arthur Rambo "Vowels". Translated by L. Martynov)

I do not dreamed of all this hypersensitive poet?

The search, however, showed that for many musicians there is an undoubted permanent connection between musical sounds (and tonalities) and color. The Lithuanian artist and composer Mikaloyus Čiurlionis (1875-1911) wrote about this connection, and the Russian composer Alexander Skryabin (1872-1915), the most interesting: whose experiments continue in our country and abroad, is also known as the inventor of color music. But still, musical sounds are one thing; and the sounds of speech are different, although there are common components between them.

Consider the ratio of the sound of speech and meaning in simple examples. Without thinking, answer the questions:

- Which sound is more - and or o?

-What sound is coarser - and or r?

-What sound is lighter - Oh or s

The overwhelming majority of Russian speakers in the answers to the questions posed will be unanimous. Of course, O is “more” I, and R is “rougher”. Oh, naturally, "lighter" than Y. What is the trick?

It can be assumed that the sounds of speech in the mind are not indifferent to the meaning. From a similar hypothesis proceeded linguist A. P. Zhuravlev.

A large number of subjects (in total - many thousands) of students, schoolchildren, people representing various other social groups (gender, age, occupation) were offered all “sounding letters” of the Russian alphabet written on sheets of paper. And the following scale of properties was perpendicular to each zvukokukve: quiet, loud; light dark; strong, weak; dull, brilliant; rough, smooth, large, small, etc. At the intersection of the strings of "letter" and "property" in the cell, the subject should have

to put the “+” sign (if this property seemed to him suitable for the characterization of the sound letter) or “-” (if the property was in no way associated with the sound letter). Most of the subjects were convinced that there is no connection between sound letters and the proposed properties. But since the task had to be completed, the pros and cons were placed (“as God puts it to his soul,” so explained one of the subjects). The technique used by Zhuravlev goes back to the “semantic differential” method known in psychology, which was created by the American psycholinguist Charles Osgood.

As a result of numerous experiments, however, it turned out that the number of pros and cons was not distributed in a random order, as is the case, say, in the distribution of “heads and tails” falling when throwing coins in a large number of experiments (in these cases the number of different drops a ratio of 50 to 50, i.e. the probability of each side of a coin falling out is 0.5). Practically none of the subjects rated the sound letters "u" and "sh" as "light", "smooth", "s" - as "gentle", "and" - as "big", etc. Computer processing of the results of experiments was confirmed by unanimity. most of the subjects regarding the above properties. Consequently, the connection between the sound of speech fragments and real-tactile images is real. The desired concepts of speech sounds are also, therefore, real.

So A. P. Zhuravlev proved that the sounds of speech are meaningful, meaningful. The meaning that speech sounds convey is called a phonetic meaning.

But how does a phonetic meaning correlate with a lexical, conceptual meaning?

Let's turn to the alphabetical list of words of our language.

And (g) ukat, gasp

Mumble, thump, mumble

Giggle, buzz gnawing, crashing

Tinker

Itch

Buzz

Hiccup

Squeeze, grunt quack

Scream

Fucking

Squeak

Growl

Whistle, lisp

Stomp

Hoot

To fuck

Crunch, oink, poke

Poke

Tweet

Rustle hiss, rustle

It is easy to see that all these units of the Russian language are onomatopoeic, almost all of them are verbs, and that almost all of them mean phonations produced by man or animals. It is also clear that not all such units of our language are given and the nests of words formed on such roots are not shown at all.

Take the word "drum" (obviously onomatopoeic, though not of Russian origin) and see the derivatives: drumming, drummer, drums, drumming ... So, in every modern developed language there are up to 2 - 3 thousand such words, and this is a lot. The proportion of such words in some languages is very large to this day, for example, in the Nanai language of Russia, in the Ewe language in Sudan (Africa). One involuntarily recalls the so-called "onomatopoeic theory" of the origin of the human language, known since antiquity and the medieval era (we still will talk about it in one of the chapters). Opponents of this theory put forward claims-questions to it: how did the designations of "non-sounding" subjects arise? How did the names of abstract concepts like “class of mammals” or “relation” appear? How could the numerical designation of numbers and the number itself appear?

At first glance, the claims are serious, if we assume that human language arose immediately in the approximate form in which we are seeing it today. But such a view is unjustifiable and anti-evolutionary: the primitive language could not and cannot have signs to designate abstract concepts that could not be in the thinking of primitive man. Therefore, in today's so-called "primitive languages" there are few units to designate the abstract. Even in. the hieroglyphs of modern (by no means primitive, but one of the most ancient) Chinese hieroglyphs to designate the concept of “tree” is in its shape similar to the drawing of a tree, and to designate the concept of “forest” they use the image of three hieroglyphs “tree”. Agree that it is simpler and more specific than a certain inflection for the designation of the plural in Russian, French or English. Such a hieroglyphic principle, as in Chinese, should be considered the principle of "primary (primary) motivation" form of the sign . Similarly, the shape of the sign of a language like “pig” or “tremble” should also be considered primary motivated: “pig” - from phonation of life

but the combination of "others", as it were, copies (in other languages: tr, gr, etc.) audible and inaudible vibrations with the help of a vibrating movement of the tip of the tongue. These kind of “copies” of an association are called “ ideophones ” in linguistics. These include the designations of fast flashing, sparking, fast movement in general: “fuck - and no!” - we say, as if we hear the sound of a flitting bird; and we can talk not about her at all, but about a raced cyclist or a runner. Professor S. V. Voronin analyzed in detail in a series of his works in detail and comprehensively various types of sound symbolism on the material of various languages.

In children's speech and in poetic creativity, cases of the invention of onomatopoeia and ideophones are very common. This is also a significant fact - for some reason, the child or the poet has few existing forms of language!

“Mandolin mandinal, tundudel cello” - wrote V. Mayakovsky. Why not write "spoke, imitating the mandolin and cello"? Yes, because onomatopoeia itself is shorter and more expressive than a more lengthy and sluggish description in other words. For the same reason, Deniska from the “Deniskin Stories” by the writer V. Dragunsky invents many of his own onomatopoeia, which all readers perfectly understand from the context. Here is another fact in favor of the “theory of onomatopoeia”: the speech of a primitive man was mainly situational (hence it is clear what exactly is called in speech); to imitate (to be understood) is much easier than to invent a "conventional sign". It is not by chance that in the children's speech of recent times the word “tik-tak” is used to designate hours, which showed (and allowed to listen) to a child. Modern clock-scoreboards can no longer be called "tick-toe" ...

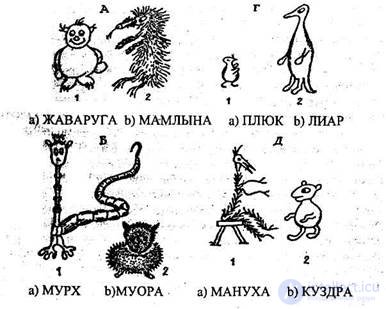

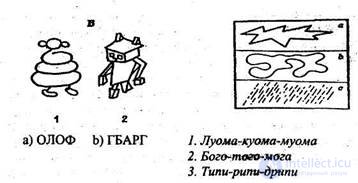

The sound image of the word can be focused not only on onomatopoeia. One of the authors of this book in the late 60s to confirm this thought held the experience that we offer our readers. On the pages of the newspaper "Week" were published drawings of non-existent animals, various geometric shapes, etc. Parallel to the drawings, non-existent words (quasi words) were cited, which were specially selected in accordance with the phonosemantic data on the nature of the drawings. Readers had to determine who is who? We offer readers of our book to spend similar

experiments with relatives and acquaintances (see figure on page 15. The key for the solution is at the end of the paragraph). Experiments have shown that the sounds of a word are capable of conveying the most diverse characteristic properties of objects, which are denoted by this word.

What is the psychological nature of this phenomenon?

Russian psychologist and world-famous neurolinguist Alexander Romanovich Luria once told an amazing thing to his students at a lecture. He asked to ponder over the phrases of Russian and other languages, where sensations and perceptions of properties and phenomena are designated together. For example, a warm word (the word is perceived by the ear or visually, and the temperature through the receptors of our skin), a cold look (the look is perceived visually, and the temperature is again by the skin), a salty joke, a bitter reproach, a sweet lie (here, taste and taste which, it would seem, can not be). One of the acquaintances of A.R. Luria complained to patients that on the way to the place of service he had to pass by the “intolerably sour fence”. The psychologist was shown this fence - it was poisonous-green, unpleasant to the eyes, but it didn’t cause any taste sensations to the scientist.

It seemed to Natasha Rostova from “War and Peace” of L. N. Tolstoy that her close people were somehow strangely associated in her perception with certain colors and even certain objects (after reading the novel, you can find out exactly how it was with Natasha). “Strange” - because only a few people have such associations. But the above phrases of the Russian language do not cause us any protest! It means that they are regular, they correspond to some of our unconscious associations. And then: screaming clothes, wet whisper, sharp (from the word cut) sound, soft contour (“soft” - is a tactile sensation, and “contour” is visual), for some reason hard frost, light touch (“touch” - tactile sensation, and “light” - the quality of gravitational sensation), hard look, subtle smile ... If you get acquainted with the musical terminology, it turns out that the chord can be “spicy”, “tasty”, the note can be taken “spicy” , you can play "hot" or "chilly", etc., etc.

A. R. Luria suggested that the psychophysiological mechanism of this kind of connection of sensations fixed in language consists in the fact that nerve impulses coming from our receptors (sense organs) in the subcortical zone induce (excite) each other, since the neuroconductive pathways close to each other. The resulting so-feeling was called the term "synesthesia" (this is the exact translation of the word "so-feeling"), which entered modern psychology and psycholinguistics for use in all languages in the scientific world.

The mechanism of action of synaesthesia in speech activity is well illustrated by the experiments of E. I. Krasnikova. A text (an alleged newspaper article), differing only in two words, was proposed to two groups of subjects for reading. We give both options completely.

Dereliction of duty

one

One of the Western Sunday newspapers - Nibjet Fage apologized to readers for the fact that in the next issue there is no permanent heading. "Where to go to eat", advertising restaurants, cafes, bars. The editors explained that the reporter supplying the materials for this column fell ill, having been poisoned in the Choffet restaurant on duty.

2

One of the Western Sunday newspapers, Hamman Mod, apologized to readers for the fact that there was no regular “Where to go to eat” rubric advertising restaurants, cafes and bars in the next issue. The editors explained that the reporter supplying materials for this column fell ill, having been poisoned at Haddock restaurant while on duty.

The experiment participants were asked a strange, at first glance, question: “What do you think the dish poisoned the reporter - hot or cold?” Most interestingly, the answers were strikingly uniform: most of the first group respondents answered, “It seems to me that the reporter was poisoned hot dish "; in the second group, they responded equally unanimously "It seems to me that the reporter was poisoned with a cold dish."

The clue to the test subject was the words "Nibdzhet feych", "Choffet" and "Khamen Mod", "Hzddok." If we sum up the phonetic meanings of the sounds that make up these words (according to A. P. Zhuravlev), it turns out that the first two are composed mainly of “hot sounds”, and the second two are from “cold” sounds. The synesthetic effect caused the participants to choose the experience of the “hot” or “cold” option.

Before drawing a conclusion, we will describe another similar experiment. Again two groups of participants were offered two almost identical texts:

one

... On this lake in the summer fishing is good both with float fishing rods and spinning, of course, if there is a boat that the local Zippeg hostel can provide you.

2

... On this lake in the summer fishing is good and float fishing rods, and spinning, of course, if there is a boat that you can provide the local campsite "Evellope".

The question this time was this: “Which shores of this lake are cut or rounded?” And again, the subjects of different groups, without saying a word, answered in the same way. Those who read the first version, argued that, in their opinion, the banks of the lake are rugged; those who were offered the second option are rounded. Analysis of the phonosemantic structure of the words “Zippeg” and “The Aelope” (which, as in the first case, were naturally selected in advance) shows that the first consists of “angular” sounds, and the second - from the sounds of “rounded”.

The results of the described experiments confirmed the data obtained by A. P. Zhuravlev. They showed, firstly, that not only sounds taken in isolation, but also words have a phonetic meaning , and secondly, that the phonosemantic content of the text is capable at an unconscious level to influence the course of semantic perception of a message .

Trying to determine the nature of the relationship between the phonetic and lexical meanings of the word, A. P. Zhuravlev again turned to the help of electronic computer technology. He used a formula by which not only a person, but also a computer, can determine the total phonosemantic filling of a word. Computer analysis significantly accelerated the research process. He allowed in a few minutes to identify the phonetic content of groups of words and even significant in volume texts.

The first words that were subjected to computer analysis, were the designation of sound phenomena. Here are the characteristics of the sound of these tokens.

Accord - beautiful, bright, loud

Bass - manly, strong, loud

Explosion - big, rough, strong, scary, loud

Thunder - rough, strong, angry

Rumble - coarse, strong, grungy

Ringing-loud

Babble - good, small, gentle, weak, silent

Nabat - strong, loud

Shout - loud

Squeak - small, weak, silent

Roar - big, rough, active, strong, scary, loud

Tish - quiet

Crackle - rough, angular

Snoring - bad, rough, grungy

Rustle - rough, quiet

Echo - loud

As we see, here the correspondence of the lexical and phonetic values is manifested quite clearly. And what about the other, "normal" words of the Russian language?Computer analysis has shown that a significant part (using such a careful formulation) of vocabulary in its sound content corresponds to the conceptual content. Let us give at random examples from the book of A. P. Zhuravlev.

Watermelon - big, smooth

Diamond - beautiful, smooth, bright

Birch - bright, bright

Fight - courageous, active, strong

Wave - active, smooth, rounded.

Good - good, strong, majestic

Gold - light, majestic

Blasphemy - dark, scary, base

Love is good, gentle,

Mimosa - gentle, feminine

Bride - gentle, bright, beautiful

Sadness - dim, sad, silent.

Spider - dark, scary, dull, silent

Mind - active, strong, majestic, mighty

The river is strong, fast, agile.

Freedom - active, strong, majestic, bright

Tulip - delicate, beautiful

Dodge-low

Hooligan - bad, rude, base

Monster - scary, bright

Yula-rounded

Jaguar - active, strong, beautiful

The given examples show that the sound form of words often carries with it a kind of “support” of the conceptual content of the word, helping the listener to better understand the dictionary meaning.

By the way, is

onosemantic support is usually in the use of expressive-stylistic vocabulary. This statement can be illustrated by analyzing the phonetic meaning of different designations of the same subject.

| Scale | beautiful - - - - repulsive | ||||

| The words | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.5 |

| Evaluation | face | face | muzzle | snout | mug |

(synonymous series), for example, the words "face." We give an assessment (using a five-point system) to the sounds that are included in these words, one parameter at a time - “beautiful - repulsive”.

По мере изменения экспрессивно-стилистического значения слова изменяется и его фонетическое значение, от «красивого» в возвышенном слове лик до отталкивающего в слове - харя .

Итак, мы убедились в том, что фонетические средства языка в речевой деятельности выступают достаточно эффективным и действенным средством передачи информации, средством воздействия на процесс восприятия речевого сообщения.

Законы фоносемантики наиболее наглядно проявляются в художественных - главным образом, стихотворных - текстах. Обычно это разного рода звуковые образы, созданные посредством звукоподражания. Достаточно вспомнить начало стихотворения К. Бальмонта «Камыши».

Полночной порою в болотной глуши

Чуть слышно, бесшумно шуршат камыши...

Нагнетание шипящих согласных создает ощущение шуршания.

Более сложные фоносемантические поэтические опыты мы можем найти у Велимира Хлебникова. Хлебников - наиболее «психолингвистический» поэт. В своих художественных экспериментах, в эстетических декларациях он во многом предугадал направление поисков теории речевой деятельности и даже предвосхитил ее открытия. Поэт мечтал создать универсальный «заумный язык» - язык, основанный только на общих для всех людей фонетических значений.

Язык, считал Хлебников, подобен игре, в которой «из тряпочек звука сшиты куклы для всех вещей мира. Люди, говорящие на одном языке, - участники этой игры. Для людей, говорящих на другом языке, такие звуковые куклы - просто собрание звуковых тряпочек. Итак, слово - звуковая кукла, словарь - собрание игрушек. Но язык естественно развивался из немногих основных единиц азбуки; согласные и гласные звуки были струнами этой игры в звуковые куклы. А если брать сочетания этих звуков в вольном порядке, например: бобэоби или дыр бул щ<ы>л , или Манч! Манч! чи брео зо! - то такие слова не принадлежат ни к

какому языку, но в то же время что-то говорят, что-то неуловимое, но все-таки существующее».

Свои замыслы поэт пытался воплотить в своих творениях. Вот, к примеру, ставшее классическим «заумное» стихотворение.

Бобэоби пелись губы,

Вээоми пелись взоры,

Пиээо пелись брови,

Лиэээй пелся облик,

Гзи-гзи-гзэо пелась цепь.

Так на холсте каких-то соответствий

Вне протяжения жило Лицо.

В начале нашего рассказа о фоносемантике мы привели стихотворение Артура Рембо, построенного на синестезических связях звука и цвета. Теперь, после знакомства с результатами психолингвистических исследования проблемы «звук и смысл» читателя уже не может удивить ход поэтической мысли французского символиста. Более того, мы можем сравнить его цветозвуковые образы с научными данными. Опыты А. П. Журавлева показали, что гласные имеют в сознании людей следующий соответствия:

А - густо-красный

Я - ярко-красный

О - светло-желтый или белый

Е - зеленый

Э - зеленоватый

И - синий

Й-синеватый.

У - темно-синий, сине-зеленый, лиловый

Ю - голубоватый, сиреневый

Ы - мрачный тёмно-коричневый или чёрный

Как видим, цветоощущение Рембо не соответствует среднестатистическим нормам. Как показали исследования Л. П. Прокофьевой, индивидуальная синестезия присуща и некоторым русским литераторам, например, В. Набокову. Однако, чтобы восстановить справедливость, мы закончим разговор о фоносемантике цитатой из более «правильного» стихотворения поэта-филолога В. Г. Руделева, которое так и называется «Звуки».

Язык -

это слов драгоценные россыпи.

Только они

что-то и значат:

«Что вы читаете, принц? -

Слова, слова, слова...»

But

как прекрасны

составляющие слов-

красное А -

упругое,

как резиновый мячик,

зеленое У-

вытянутое, как пальма,

синее И-

нежное,

как воздушный шар,

желтое О —

как молодой подсолнух.

О серебряные соноры

Р и Л!

О синее Н,

cut from foil.

O brown G, K, X:

first -

from smooth skin,

the second is

from suede,

the third - affectionate velvet.

We fled to Volkhonka

listen to how they sound

sounds cut by the separator.

Separately!

But the key to the task with pictures:

BUT

B

AT

R

D

E

a2

a2

a1

a1

a2

a2

b1

b1

b2

b1

b1

b1

c3

Comments

To leave a comment

Psycholinguistics

Terms: Psycholinguistics