Lecture

In a holistic behavioral response, needs, motivations and emotions appear in inseparable unity, however, they can be divided both in terms of content and experimentally, since they reflect the activity of, although closely interacting, specialized departments of the CNS, on the one hand, and perform different functions in providing behavior , with another.

Needs - a form of communication of the organism with the outside world and the source of its activity. It is the needs, being the inner essential forces of the organism, that induce it to various forms of activity (activity) necessary for the preservation and development of the individual and kind. The needs of living beings are extremely diverse. There are different approaches to their classification, however, most researchers identify three types of needs: biological, social and ideal .

Biological needs. In its primary biological forms, the need acts as a need experienced by the body in something in the external environment and necessary for its vital activity. Biological needs are due to the need to maintain the constancy of the internal environment of the body. The activity they encourage is always aimed at achieving the optimal level of functioning of the main life processes. This activity resumes when the parameters of the internal environment deviate from the optimal level and stops when it is reached.

Biological needs (for food, water, security, etc.) are peculiar to both humans and animals. However, most of the needs of animals is instinctive. Instincts can be considered as functional systems in which not only the properties of external objects (or living beings) capable of satisfying these needs are genetically “predetermined”, but also the main sequence of behavioral acts leading to the achievement of a useful result.

Human biological needs are different from similar needs of animals. The main difference lies, above all, in the level of socialization of human biological needs, which can significantly change under the influence of sociocultural factors. For example, the socialization of food needs has generated a highly valued art of cooking and aestheticizing the process of food consumption. It is also known that in some cases people are able to suppress biological needs (food, sex, etc.) in themselves, guided by the goals of the highest order.

Needs that ensure the normal functioning of the body are well known - these are needs for food, water, optimal environmental conditions (oxygen content in air, atmospheric pressure, ambient temperature, etc.). A special place in this series is the need for security. Dissatisfaction with this need creates feelings such as anxiety and fear.

Social and ideal needs. The physiology of higher nervous activity approaches the definition of the nature and composition of social and ideal needs, based on the idea of the existence of an innate unconditioned-reflex basis of behavior that is universal in nature and manifests itself in the behavior of both higher animals and man.

The need for novelty lies at the heart of the individual's orienting-research activity and provides him with the possibility of active knowledge of the surrounding world. Two groups of factors are related to the actualization of this need: the lack of activation, which leads to the search for new incentives (complex and changeable), and the lack of information, which forces us to look for ways to reduce uncertainty.

When describing the need sphere of a person, sometimes the information need is highlighted as a special kind of need, which is not a “sensory hunger” as such, but a need for diverse stimulations. Dissatisfaction with the information needs can lead to violations of not only the mental balance of a person, but also the vital activity of his body.

For example, in experiments on complete sensory isolation of a healthy person, they are immersed in a special bath, which makes it possible to almost completely isolate him from sensory stimuli of various modalities (acoustic, visual, tactile, etc.). After some time (for each person it is different), people begin to experience mental discomfort (loss of sensation of their body, hallucinations, nightmares), which can lead to a nervous breakdown.

Simple monotonous stimulation of the receptors (for example, monotonous sound) improves the state only for a short time. However, if the same incentives to present not rhythmically, but in a random order, the person’s well-being improves. With the invariance of the parameters of the stimulus, a moment of uncertainty is introduced, and with it the possibility of a forecast carrying a certain meaning or information. This contributes to the normalization of the mental state of a person. Thus, the information need, although related to ideal needs, acquires a vital or vital significance from a person.

One of the natural prerequisites for learning, the subtle physiological mechanisms of which are not yet known, is the need for competence. It manifests itself in the desire to repeat the same action until the complete success of its execution, and is found in the behavior of higher animals and often small children. The adaptive sense of this need is obvious: its satisfaction creates the basis for mastering instrumental skills, i.e. basis for learning in the widest sense of the word.

The need to overcome (the "reflex of freedom", by definition of IP Pavlov) arises when there is a real obstacle and is determined by the desire of a living being to overcome this obstacle. The freedom reflex is most pronounced in wild animals, the stimulus for its actualization is a restriction (obstacle), and unconditional reinforcement is the overcoming of this obstacle. The adaptive significance of this need is primarily associated with the animal's urge to expand habitat, and ultimately to improve the conditions for the survival of the species.

From the point of view of evolutionary physiology, the listed social and ideal needs must also have their representation in the motivational and need sphere of a person. In the course of individual development, basic needs are socialized, are included in the personal context and acquire a qualitatively new content, becoming the motives of activity.

The physiological conditions for the emergence of needs are an insufficiently developed problem, and some certainty currently exists only in relation to such vital needs as the need for food and water. From the point of view of psychology, hunger and thirst are homeostatic drives - drives aimed at getting the body sufficient to ensure the survival of water and food. These drives are innate and do not require special learning, but during life they can be modified by various environmental influences.

The nature of hunger. Energy balance in humans is maintained, provided that the energy input corresponds to its expenditure on muscular work, chemical processes (growth and restoration of tissues) and heat loss. Lack of food causes a feeling of hunger, which initiates behavior aimed at finding food. Under what physiological conditions does hunger arise? Initially it was assumed that the feeling of hunger arises as a result of contractions of an empty stomach, which can be perceived by mechano-receptors located in the walls of the stomach.

According to modern concepts, the glucose dissolved in the blood plays a decisive role in this. Normally, regardless of the quality of food consumed, the concentration of glucose in the blood is maintained in the range of 0.8 to 1.0 g / l. In the diencephalon, liver, vascular walls of the circulatory system are chemoreceptors that respond to the concentration of glucose in the blood, the so-called glucor receptors. In response to a decrease in blood glucose, they contribute to the emergence of hunger. It is assumed that the feeling of hunger may also occur as a result of a lack in the body of metabolic products of proteins and fats.

In addition, a certain role in the occurrence of hunger can play the current conditions of life. It is known that with a decrease in ambient temperature in warm-blooded animals, food consumption increases, and in an amount inversely proportional to the temperature available. Thus, internal thermoreceptors can serve as a source of stimulation, which contributes to the sensation of hunger.

Along with the physiological, there are psychological factors that regulate the emergence of hunger. Diet, including the rhythm of food consumption, the duration of intervals between meals, its qualitative composition and quantity certainly affect the emergence of a feeling of hunger.

The pursuit of certain foods is called appetite. It can occur with the sensation of hunger and beyond (for example, at the sight or description of a particularly delicious dish). A specific appetite may reflect a real shortage of any component in the composition of the food, for example, craving for salty foods may occur as a result of the loss of a significant amount of salt by the body. However, this connection is not always traced. The preference of some types of food and aversion to others are determined by the individual experience of human education and cultural traditions.

The process of absorption of food usually stops long before as a result of its digestion the energy deficit disappears, which caused a feeling of hunger and prompted the beginning of the absorption of food. The sum of the processes that force the completion of this act is called saturation. The feeling of satiety is always accompanied by the release of tension (as it is associated with the activation of the parasympathetic system) and positive emotions, therefore, it is more than just the disappearance of hunger.

The nature of thirst. An adult’s body contains approximately 75% water. If you lose more water than 0.5% of your body weight (about 350 ml of a person who has a body weight of 70 kg), you will feel thirsty. Thirst is a general sensation based on the combined action of many types of receptors located both on the periphery and in the brain. The main nervous structures responsible for the regulation of water-salt balance are located in the intermediate brain, mainly in the hypothalamus. In its anterior sections, so-called osmoreceptors are located, which are activated when the intracellular salt concentration increases, i.e. when cells lose water. Osmoreceptors are called thirst receptors, caused by a lack of water in the cells. In addition to them, other factors, such as mouth and pharyngeal receptors (creating a feeling of dryness), stretching receptors in the walls of large veins and others, can also take part in the formation of thirst. It is important to emphasize that there is no adaptation to the sensation of thirst; therefore, the only means of eliminating it is water consumption.

Biochemical correlates of sensation needs. According to some data, the need for additional stimulation can be determined by some biochemical features of a person. For example, in the well-known studies of the American psychologist M. Zackerman, the tendency of a person to search for new experiences, the desire for physical and social risk, was studied. This propensity is defined as the "search for sensations." With the help of a special questionnaire, it is possible to assess the human need for novelty, strong and thrill. It is established that the individual level of need for sensations has its own biochemical prerequisites. The degree of need for sensation is negatively related to the level of the following biochemical parameters: monoamine oxidase (MAO), endorphins and sex hormones .

The function of monoamine oxidase is to control and limit the level of some mediators (in particular, norepinephrine, dopamine). These mediators ensure the functioning of the neurons of the catecholamine-energy system related to the regulation of the emotional states of the individual. If the content of MAO in neurons is reduced (compared with the norm), biochemical control over the action of these mediators is weakened. Endorphins, biologically active substances produced in the brain, reduce pain sensitivity and have a calming effect on the human psyche. Sex hormones (androgens and estrogens) are associated with processes of automating and feminization.

In other words, individuals who are less produced in the body of MAO, endorphins and sex hormones, are more likely to be inclined to form behavior, expressed in the search for a strong additional stimulation. Zuckerman suggested that the search for sensations is associated with the need to ensure the optimal level of activation in the catecholaminoergic system. Therefore, individuals with a low level of catecholamine production will apparently look for strong sensations in order to raise the activity of this system to an optimal level.

This example suggests that over time, biochemical features can be found that create conditions for the formation of some, not only vital, but also ideal human needs. However, it should not be overlooked that the correlation as a method of analysis does not provide a basis for assessing cause-effect relationships. In principle, one cannot exclude the fact that the listed biochemical features themselves arise as a result of behavior aimed at the search for sensations, which is formed as a result of the action of some other factors that are currently unknown (maybe social).

The term "motivation" literally means "that which causes movement," i.e. In a broad sense, motivation can be considered as a factor (mechanism) determining behavior.

Motivation. The need, growing into motivation, activates the central nervous system and other body systems. At the same time, it acts as an energy factor ("blind power", according to IP Pavlov), which induces the body to a certain behavior.

Do not identify motivation and needs. Needs do not always translate into motivational arousal, while at the same time, without proper motivational arousal, it is impossible to satisfy the corresponding needs. In many life situations, the existing need for one reason or another is not accompanied by a motivational urge to action. Figuratively speaking, the need says “what the body needs,” and motivation mobilizes the body’s forces to achieve the “right”.

Motivational arousal can be considered as a special, integrated state of the brain, in which, on the basis of the influence of subcortical structures, the cerebral cortex is involved in the activity of the cerebral cortex. As a result, the living entity begins to purposefully search for ways and objects to satisfy the corresponding need.

The essence of these processes was clearly expressed by A.N. Leontyev in the words: motivation is an objectified need, or "self-directed behavior."

The particular question is what is the mechanism for the development of the need for motivation. In relation to some biological needs (hunger, thirst), this mechanism, as shown above, is associated with the principle of homeostasis. According to this principle, the internal environment of the body should always remain constant, which is determined by the presence of a number of constant parameters (hard constants), the deviation from which leads to severe disruption of vital activity. Examples of such constants are: blood glucose level, oxygen content, osmotic pressure, etc.

As a result of the continuous metabolism, these constants can shift.Their deviation from the required level leads to the inclusion of self-regulation mechanisms that ensure the return of constants to the initial level. To some extent, these deviations can be compensated by internal resources. However, internal capabilities are limited. In this case, the body activates processes aimed at obtaining the necessary substances from the outside. It is this moment, which characterizes, for example, the change of an important constant in the blood, can be regarded as the emergence of need. As domestic resources are depleted, there is a gradual increase in demand. Upon reaching a certain threshold value, the need leads to the development of motivational arousal, which should lead to the satisfaction of the need from external sources.

В отношении других потребностей картина не столь очевидна.

Тем не менее есть основания полагать, что и здесь действует принцип "порогового значения". Потребность перестает в мотивацию лишь по достижении некоторого уровня, при превышении этого условного порога человек, как правило, не может игнорировать нарастающую потребность и подчиненную ей мотивацию.

Виды мотивации. В любой мотивации необходимо различать две составляющие: энергетическую и направляющую . Первая отражает меру напряжения потребности, вторая — специфику или семантическое содержание потребности. Таким образом, мотивации различаются по силе и по содержанию. В первом случае они варьируют в диапазоне от слабой до сильной. Во втором — прямо связаны с потребностью, на удовлетворение которой направлены.

Соответственно так же, как и потребности, мотивации принято разделять на низшие (первичные, простые, биологические) и высшие (вторичные, сложные, социальные). Примерами биологических мотиваций могут служить голод, жажда, страх, агрессия, половое влечение, забота о потомстве.

Biological and social motivations determine the vast majority of forms of purposeful activity of living beings.

Dominant motivational arousal. Because of the diversity, different needs often coexist at the same time, prompting the individual to different, sometimes mutually exclusive styles of behavior. For example, the need for security (fear) and the need to protect your child (maternal instinct) can compete. That is why a kind of “struggle” of motivations and building up their hierarchy often happens.

В формировании мотиваций и их иерархической смене ведущую роль играет принцип доминанты, сформулированный А.А. Ухтомским (1925). По этому принципу, в каждый момент времени доминирует та мотивация, в основе которой лежит наиболее важная биологическая потребность. Сила потребности, т.е. величина отклонения физиологических констант или концентрации соответствующих гормональных факторов, получает свое отражение в величине мотивационного возбуждения структур лимбической системы и определяет его доминантный характер.

Консервативный характер доминанты проявляется в ее инертности, устойчивости и длительности. В этом заключается ее большой биологический смысл для организма, который стремится к удовлетворению этой биологической потребности в случайной и постоянно меняющейся внешней среде. В физиологическом смысле такое состояние доминанты характеризуется определенным уровнем возбудимости центральных структур, обеспечивающей их высокую отзывчивость и "впечатлительность" к разнообразным воздействиям.

Доминирующее мотивационное возбуждение, побуждающее к определенному целенаправленному поведению, сохраняется до тех пор, пока не будет удовлетворена вызвавшая его потребность. При этом все посторонние раздражители только усиливают мотивацию, а одновременно с этим все другие виды деятельности подавляются. Однако в экстремальных ситуациях доминирующая мотивация обладает способностью трансформировать свою направленность, а следовательно, и реорганизовывать целостный поведенческий акт, благодаря чему организм оказывается способным достигать новых, неадекватных исходной потребности результатов целенаправленной деятельности. Например, доминанта, созданная страхом, в исключительных случаях может превратиться в свою противоположность — доминанту ярости.

Нейронные механизмы мотивации. Возбуждение мотивационных подкорковых центров осуществляется по механизму триггера: возникая, оно как бы накапливается до критического уровня, когда нервные клетки начинают посылать определенные разряды и сохраняют такую активность до удовлетворения потребности.

Мотивационное возбуждение усиливает работу нейронов, степень разброса их активности, что проявляется в нерегулярном характере импульсной активности нейронов разных уровней мозга. Удовлетворение потребности, напротив, уменьшает степень разброса в активности нейронов, переводя нерегулярную активность нейронов различных уровней мозга — в регулярную.

Доминирующая мотивация отражается в характерном распределении межстимульных интервалов у нейронов различных отделов мозга. При этом распределение межстимульных интервалов для различных биологических мотиваций (например, жажда, голод и т.п.) носит специфический характер. Однако практически в любой области мозга можно найти значительное число нейронов со специфическим для каждой мотивации распределением межстимульных интервалов. Последнее, по мнению К.В. Судакова, позволяет говорить о голографическом принципе отражения доминирующей мотивации в деятельности отдельных структур и элементов мозга.

Физиологические теории мотиваций. Первые представления о физиологической природе мотиваций были основаны на интерпретации сигналов, поступающих от периферических органов. При этом считалось, что мотивации возникают в результате стремления организма избежать неприятных ощущений, сопровождающих различные побуждения. Например, животное утоляет жажду, чтобы избавиться от сухости в полости рта и глотки, поедает пищу, чтобы избавиться от мышечных сокращений пустого желудка и т.д.

Физиологические теории мотиваций. Первые представления о физиологической природе мотиваций были основаны на интерпретации сигналов, поступающих от периферических органов. При этом считалось, что мотивации возникают в результате стремления организма избежать неприятных ощущений, сопровождающих различные побуждения. Например, животное утоляет жажду, чтобы избавиться от сухости в полости рта и глотки, поедает пищу, чтобы избавиться от мышечных сокращений пустого желудка и т.д.

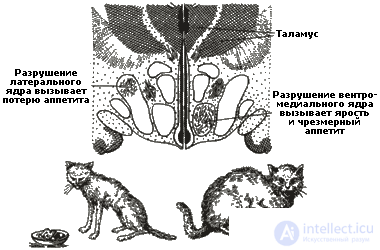

Были выдвинуты теории, в которых основное внимание уделялось гуморальным факторам мотиваций. Так, голод связывался с возникновением так называемой "голодной крови", т.е. крови с существенным отклонением от обычной разницы в концентрации глюкозы. Предполагалось, что недостаток глюкозы в крови приводит к "голодным" сокращениям желудка. Мотивация жажды также оценивалась как следствие изменения осмотического давления плазмы крови или снижения внеклеточной воды в тканях. Половое влечение ставилось в прямую зависимость от уровня половых гормонов в крови.  Действительно, в глубоких структурах мозга, как уже отмечалось, существуют хеморецепторы, специализированные на восприятии колебаний в содержании определенных химических веществ в крови. Основным центром, содержащим такие рецепторы, является гипоталамус. На этой основе была выдвинута гипоталамическая теория мотиваций, в соответствии с которой гипоталамус выполняет роль центра мотивационных состояний. Экспериментальным путем, например, было установлено, что в латеральном гипоталамусе располагается центр голода, побуждающий организм к поискам и приему пищи, а в медиальном гипоталамусе — центр насыщения, ограничивающий прием пищи. Двухстороннее разрушение латеральных ядер у подопытных животных приводит к отказу от пищи, а их стимуляция через вживленные электроды — к усиленному потреблению пищи. Разрушение некоторых участков медиального таламуса влечет за собой ожирение и повышенное потребление пищи.

Действительно, в глубоких структурах мозга, как уже отмечалось, существуют хеморецепторы, специализированные на восприятии колебаний в содержании определенных химических веществ в крови. Основным центром, содержащим такие рецепторы, является гипоталамус. На этой основе была выдвинута гипоталамическая теория мотиваций, в соответствии с которой гипоталамус выполняет роль центра мотивационных состояний. Экспериментальным путем, например, было установлено, что в латеральном гипоталамусе располагается центр голода, побуждающий организм к поискам и приему пищи, а в медиальном гипоталамусе — центр насыщения, ограничивающий прием пищи. Двухстороннее разрушение латеральных ядер у подопытных животных приводит к отказу от пищи, а их стимуляция через вживленные электроды — к усиленному потреблению пищи. Разрушение некоторых участков медиального таламуса влечет за собой ожирение и повышенное потребление пищи.

Однако гипоталамические структуры не могут рассматриваться в качестве единственных центров, регулирующих мотивационное возбуждение. Первая инстанция, куда адресуется возбуждение любого мотивационного центра гипоталамуса, — лимбическая система мозга. При усилении гипоталамического возбуждения оно начинает широко распространяться, охватывая кору больших полушарий и ретикулярную формацию. Последняя оказывает на кору головного мозга генерализованное активирующее влияние. Фронтальная кора выполняет функции построения программ поведения, направленных на удовлетворение потребностей. Именно эти влияния и составляют энергетическую основу формирования целенаправленного поведения для удовлетворения насущных потребностей.

Теория функциональных систем и мотивация. Наиболее полное психофизиологические описание поведения дает теория функциональных систем П.К. Анохина (см. тему 1 п. 1.4). Согласно теории ФС, немотивированного поведения не существует.

Мотивация активизирует работу ФС, в первую очередь афферентный синтез и акцептор результатов действия. Соответственно активируются афферентные системы (снижаются сенсорные пороги, усиливаются ориентировочные реакции) и активизируется память (актуализируются необходимые для поисковой активности образы-энграммы памяти).

Мотивация создает особое состояние ФС — "предпусковую интеграцию", которая обеспечивает готовность организма к выполнению соответствующей деятельности. Для этого состояния характерен целый ряд изменений.

Во-первых, активируется двигательная система (хотя разные формы мотивации реализуются в разных вариантах поведенческих реакций, при любых видах мотивационного напряжения возрастает уровень двигательной активности).

Во-вторых, повышается тонус симпатической нервной системы, усиливаются вегетативные реакции (возрастает ЧСС, артериальное давление, сосудистые реакции, меняется проводимость кожи). В результате возрастает собственно поисковая активность, имеющая целенаправленный характер.

Кроме того, возникают субъективные эмоциональные переживания (эти переживания имеют преимущественно негативный оттенок, во всяком случае до тех пор, пока не будет удовлетворена соответствующая потребность). Все перечисленное создает условия для оптимального выполнения предстоящего поведенческого акта.

Мотивация сохраняется на протяжении всего поведенческого акта, определяя не только начальную стадию поведения (афферентный синтез), но и все последующие: предвидение будущих результатов, принятие решения, его коррекцию на основе акцептора результатов действия и изменившейся обстановочной афферентации. Именно доминирующая мотивация "вытягивает" в аппарате акцептора результатов действия весь накопленный и врожденный поведенческий опыт, создавая тем самым определенную программу поведения. С этой точки зрения акцептор результата действия представляет доминирующую потребность организма, преобразованную мотивацией в форму опережающего возбуждения мозга.

Thus, motivation is an essential component of the functional system of behavior. It represents a special state of the organism, which, persisting throughout the entire period - from the beginning of the behavioral act to obtaining useful results - determines the purposeful behavioral activity of the organism and the nature of its response to external stimuli.

The theory of drive reduction proposed by C. Hull (Hull, 1943), as early as the middle of the twentieth century, argued that the dynamics of behavior in the presence of a motivational state (drive) is directly caused by the desire for a minimum level of activation, which provides the body with stress relief and a sense of peace. According to this theory, the body seeks to reduce excess stress caused by a motivational drive.

The theory of drive reduction proposed by C. Hull (Hull, 1943), as early as the middle of the twentieth century, argued that the dynamics of behavior in the presence of a motivational state (drive) is directly caused by the desire for a minimum level of activation, which provides the body with stress relief and a sense of peace. According to this theory, the body seeks to reduce excess stress caused by a motivational drive.

However, as further studies have shown, the desire to reduce the drive is not the only factor determining behavior. Reduction drive can not explain all types of behavior aimed at finding a new additional stimulation. Apparently, in all life situations, the body tends not to rest, but to some optimal level of activation, which allows it to function in the most efficient way. In those cases when the voltage is too strong, this will be the behavior aimed at removing the excess voltage, in others, when the activation level is very low, the behavior will be directed to the search for additional stimulation providing the required level of activation. The subjective feeling of a person at the optimal level of activation seems to correspond most of all to the state of “operational rest” (see topic 3, p. 3.1).

Individual differences in the level of activation. The above agrees well with the views of G. Eysenck (Eysensk, 1985), according to which individual differences in such personality traits as extraversion - introversion depend on the functioning of the ascending reticular activating system (see also topic 3, p. 3.1). This structure controls the level of activation of the cerebral cortex.

Individual differences in the level of activation. The above agrees well with the views of G. Eysenck (Eysensk, 1985), according to which individual differences in such personality traits as extraversion - introversion depend on the functioning of the ascending reticular activating system (see also topic 3, p. 3.1). This structure controls the level of activation of the cerebral cortex.

Eysenck claims that in silence (for example, when working in a library) extroverts, in which the normal structure of the cortex is not too highly activated, can experience unpleasant sensations, since their level of cortical activation turns out to be significantly lower than the point at which agitation a feeling of mental comfort is experienced. . Therefore, they have a need to do something (talk to others, listen to music on headphones, take breaks). Since introverts, by contrast, are highly activated, any further increase in the level of activation is unpleasant for them. In other words, extroverts need constant environmental "noise" to bring the level of arousal of the cortex to a state that brings satisfaction. At the same time, introverts do not feel such a need, and they will really consider such stimulation as super-exciting and therefore unpleasant. Empirical data show that introverts are more active than extroverts found in 22 out of 38 studies, thus Aysenck’s theory is more likely to be confirmed.

Thus, the theory of Eysenck testifies in favor of the fact that behavior acts as a tool that modulates the level of activation, increasing or decreasing the latter, depending on the needs of the person.

By definition, emotions are a special class of mental processes and states associated with needs and motives, reflecting in the form of direct subjective experiences (satisfaction, joy, fear, etc.) the importance of phenomena and situations acting on an individual . Accompanying almost any manifestation of human activity, emotions are one of the main mechanisms of internal regulation of mental activity and behavior, aimed at meeting the needs.

According to the criterion of the duration of emotional phenomena, they distinguish, first, the emotional background (or emotional state), and second, the emotional response. These two classes of emotional phenomena are subject to different laws. The emotional state to a greater degree reflects the general global attitude of a person to the surrounding situation, to himself and is associated with his personal characteristics, emotional response is a short-term emotional response to a particular impact that has a situational nature. The most essential characteristics of emotions are their sign and intensity. Positive and negative emotions are always characterized by a certain intensity.

The emergence and course of emotions is closely connected with the activity of the modulating systems of the brain, and the limbic system plays a decisive role.

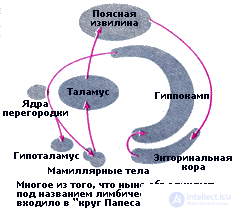

The limbic system is a complex of phylogenetically ancient deep-seated brain structures that are functionally interconnected and are involved in the regulation of the vegetative-visceral functions and behavioral responses of the body . The term "limbic system" was introduced in 1952 by Mac Lyn. However, even earlier, in 1937, Papets suggested the existence of an "anatomical" emotional ring. It included: hippocampus - arch - mamillary bodies - anterior nucleus of the thalamus - cingulate gyrus - hippocampus. Papec believed that any afferentation entering the thalamus is divided into three streams: movements, thoughts, and feelings. The stream of "feelings" circulates around the anatomical "emotional ring", thus creating the physiological basis of emotional experiences.

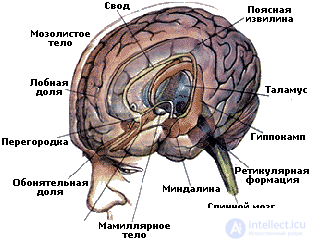

The limbic system is a complex of phylogenetically ancient deep-seated brain structures that are functionally interconnected and are involved in the regulation of the vegetative-visceral functions and behavioral responses of the body . The term "limbic system" was introduced in 1952 by Mac Lyn. However, even earlier, in 1937, Papets suggested the existence of an "anatomical" emotional ring. It included: hippocampus - arch - mamillary bodies - anterior nucleus of the thalamus - cingulate gyrus - hippocampus. Papec believed that any afferentation entering the thalamus is divided into three streams: movements, thoughts, and feelings. The stream of "feelings" circulates around the anatomical "emotional ring", thus creating the physiological basis of emotional experiences.  Papets circle formed the basis of the limbic system. In its main parts, it is similar in all mammals. In addition to the Papec ring, it is common to refer to the limbic system: some nuclei of the hypothalamus, amygdala, or amygdala (cell cluster, as large as a nut), olfactory bulb, tract and tubercle, nonspecific nuclei of the thalamus, and the midbrain reticular formation. Together, these morphological structures form a single hypothalamic-limbico-reticular system. The central part of the limbic system is the hippocampus. In addition, there is a view that the anterior frontal region is a neocortical continuation of the limbic system.

Papets circle formed the basis of the limbic system. In its main parts, it is similar in all mammals. In addition to the Papec ring, it is common to refer to the limbic system: some nuclei of the hypothalamus, amygdala, or amygdala (cell cluster, as large as a nut), olfactory bulb, tract and tubercle, nonspecific nuclei of the thalamus, and the midbrain reticular formation. Together, these morphological structures form a single hypothalamic-limbico-reticular system. The central part of the limbic system is the hippocampus. In addition, there is a view that the anterior frontal region is a neocortical continuation of the limbic system.  Nerve signals coming from all the sense organs, heading along the nerve paths of the brain stem to the cortex, pass through one or more limbic structures — the amygdala, hippocampus, or part of the hypothalamus. Signals emanating from the cortex also pass through these structures. Different departments of the limbic system are differently responsible for the formation of emotions. Their occurrence depends to a large extent on the activity of the amygdaloid complex and the cingulate gyrus. However, the limbic system takes part in the launch mainly of those emotional reactions that have already been tested in the course of life experience.

Nerve signals coming from all the sense organs, heading along the nerve paths of the brain stem to the cortex, pass through one or more limbic structures — the amygdala, hippocampus, or part of the hypothalamus. Signals emanating from the cortex also pass through these structures. Different departments of the limbic system are differently responsible for the formation of emotions. Their occurrence depends to a large extent on the activity of the amygdaloid complex and the cingulate gyrus. However, the limbic system takes part in the launch mainly of those emotional reactions that have already been tested in the course of life experience.

There is convincing evidence that a number of fundamental human emotions have an evolutionary basis. These emotions are hereditarily fixed in the limbic system.

Reticular formation. An important role in providing emotions is played by the reticular formation of the brainstem. As you know, fibers from neurons of the reticular formation go to different areas of the cerebral cortex. Most of these neurons are considered "non-specific", i.e. unlike neurons of the primary sensory zones, visual or auditory, reacting only to one type of stimuli, neurons of the reticular formation can respond to many kinds of stimuli. These neurons transmit signals from all sense organs (eyes, skin, muscles, internal organs, etc.) to the structures of the limbic system and the cerebral cortex.

Some areas of the reticular formation have more specific functions. For example, a special section of the reticular formation, called the blue spot (this is a dense collection of neurons, the processes of which form widely branching networks with one output, using norepinephrine as a mediator), is related to the awakening of emotions. From the blue spot to the thalamus, the hypothalamus, and many areas of the cortex, there are nerve paths through which the aroused emotional reaction can spread widely throughout all brain structures. According to some reports, a lack of norepinephrine in the brain leads to depression. The positive effect of electroconvulsive therapy, in most cases eliminating depression in a patient, is associated with increased synthesis and increase in the concentration of norepinephrine in the brain. The results of the study of the brain of patients who have committed suicide in a state of depression have shown that it is depleted of norepinephrine and serotonin. It is possible that norepinephrine plays a role in the occurrence of reactions that are subjectively perceived as pleasure. In any case, the lack of norepinephrine is manifested in the appearance of depressive states associated with anguish, and a lack of adrenaline is associated with anxiety depressions.

Another section of the reticular formation, called the substantia nigra, is an accumulation of neurons that also form widely branching networks with one output, but emit another mediator - dopamine, which contributes to the appearance of pleasant sensations. It is possible that he is involved in the emergence of a special mental state - euphoria.

The frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex from all parts of the cerebral cortex are most responsible for the emergence and awareness of emotional experiences. Straight neural paths from the thalamus, the limbic system, and the reticular formation go to the frontal lobes.

Injuries to people in the area of the frontal lobes of the brain show that they most often experience mood changes from euphoria to depression, as well as a peculiar loss of orientation, manifested in the inability to make plans. Sometimes mental changes are reminiscent of depression: the patient shows apathy, loss of initiative, emotional retardation, and indifference to sex. Sometimes changes are similar to psychopathic behavior: susceptibility to social signals is lost, incontinence in behavior and speech appears.

Hemispheric asymmetry and emotion. There are many facts that indicate that the left and right hemispheres of the brain make different contributions to ensuring the emotional sphere of a person. More emotiogenic is the right hemisphere. Thus, in healthy people, an advantage was found in the left half of the visual field (ie, the right hemisphere) in evaluating facial expressions, as well as in the left ear (also in the right hemisphere) - in evaluating the emotional tone of the voice and other sound manifestations of human feelings (laughter, crying) , in the perception of musical fragments. In addition, more intense expressions of emotions (facial expressions) on the left side of the face were also revealed. There is also an opinion that the left half of the face reflects more negative, the right half - positive emotions. According to some data, these differences manifest themselves in infants, in particular, in the asymmetry of mimicry in the taste perception of sweet and bitter.

It is known from the clinic that emotional disorders in the lesion of the right hemisphere are more pronounced, with a marked deterioration in the ability to evaluate and identify emotional expression in facial expressions. With left-sided lesions, patients often experience anxiety, anxiety, and fear, increasing the intensity of negative emotional experiences. Patients with lesions of the right hemisphere are more characteristic of states of complacency, gaiety, and also indifference to others. They find it difficult to assess the mood and identify the emotional components of the speech of other people. Clinical observations of patients with pathological obsessive laughter or crying show that pathological laughter is often associated with right-sided lesions, and pathological crying with left-sided ones.

The function of perceiving emotions in facial expression in patients with damaged right hemisphere suffers more than in people with damaged left hemisphere. At the same time, the sign of emotions does not matter, but the cognitive assessment of the significance of emotional words is adequate in such patients. In other words, they suffer only the perception of emotions. Right- and left-sided lesions affect temporal aspects of emotional phenomena in different ways: sudden affective changes are more often associated with lesions of the right hemisphere, and long-term emotional experiences are often associated with lesions of the left hemisphere.

According to some ideas, the left hemisphere is responsible for the perception and expression of positive emotions, and the right one - negative. Depressive experiences arising from the lesion of the left hemisphere are considered as a result of disinhibition of the right, and euphoria, often accompanying the lesion of the right hemisphere, as a result of disinhibition of the left.

There are other approaches to the description of the specificity of interhemispheric interaction in providing emotions. For example, it is suggested that the tendency of the right hemisphere to synthesize and unite a multitude of signals into a global image plays a crucial role in the development and stimulation of emotional experience. At the same time, the advantage of the left hemisphere in the analysis of individual time-ordered and well-defined parts is used to modify and weaken the emotional reactions. Thus, the cognitive and emotional functions of both hemispheres are closely related both in the cognitive sphere and in the regulation of emotions.

According to other ideas, each of the hemispheres has its own emotional "vision" of the world. At the same time, the right hemisphere, which is considered as a source of unconscious motivation, unlike the left, perceives the world around it in an unpleasant, threatening light, but it is the left hemisphere that dominates the organization of a holistic emotional experience on a conscious level. Thus, the cortical regulation of emotions is normal in the interaction of the hemispheres (see Khrest. 4.2).

The problems of the origin and functional significance of emotions in the behavior of humans and animals are the subject of constant research and discussion. Currently, there are several physiological theories of emotions.

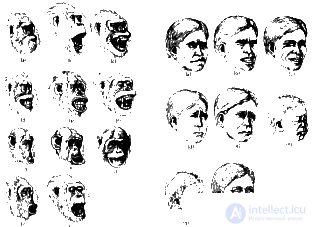

Darwin's biological theory. One of the first who singled out the regulatory role of emotions in the behavior of mammals was the eminent natural scientist Charles Darwin. His analysis of the emotional expressive movements of animals gave grounds to consider these movements as a peculiar manifestation of instinctive actions that play the role of biologically significant signals for representatives of not only his own, but also other types of animals. These emotional signals (fear, threat, joy) and the mimic and pantomimic movements that accompany them have adaptive meaning. Many of them manifest from the moment of birth and are defined as innate emotional reactions.

Darwin's biological theory. One of the first who singled out the regulatory role of emotions in the behavior of mammals was the eminent natural scientist Charles Darwin. His analysis of the emotional expressive movements of animals gave grounds to consider these movements as a peculiar manifestation of instinctive actions that play the role of biologically significant signals for representatives of not only his own, but also other types of animals. These emotional signals (fear, threat, joy) and the mimic and pantomimic movements that accompany them have adaptive meaning. Many of them manifest from the moment of birth and are defined as innate emotional reactions.

Each of us is familiar with facial expressions and pantomimics accompanying emotional experiences. From the facial expression of a person and the tension of his body, one can quite accurately determine what he experiences: fear, anger, joy, or other feelings.

So, Darwin first drew attention to a special role in the manifestation of emotions, which is played by the muscular system of the body and, first of all, those of its departments that participate in the organization of body-specific movements and facial expressions. In addition, he pointed out the importance of feedback in the regulation of emotions, emphasizing that the intensification of emotions is associated with their free external expression. On the contrary, the suppression of all external signs of emotions weakens the power of emotional experience.

However, apart from the external manifestations of emotions, with emotional arousal, there are changes in the frequency of the heart rate, respiration, muscle tension, etc. All this suggests that emotional experiences are closely related to autonomic shifts in the body. What is the nature of this connection and what physiological mechanisms underlie emotional experience?

The theory of James-Lange is one of the first theories that attempted to link emotions and autonomic shifts in the human body that accompany emotional experiences. It assumes that after perceiving the event that caused the emotion, the person experiences this emotion as a sensation of physiological changes in his own body, i.e. physical sensations are emotion itself. As James stated: "we are sad because we are crying, we are angry, because we strike, we are afraid, because we are trembling." (see fig.)

The theory of James-Lange is one of the first theories that attempted to link emotions and autonomic shifts in the human body that accompany emotional experiences. It assumes that after perceiving the event that caused the emotion, the person experiences this emotion as a sensation of physiological changes in his own body, i.e. physical sensations are emotion itself. As James stated: "we are sad because we are crying, we are angry, because we strike, we are afraid, because we are trembling." (see fig.)

The theory has been repeatedly criticized. В первую очередь отмечалось, что ошибочно само исходное положение, в соответствии с которым каждой эмоции соответствует свой собственный набор физиологических изменений. Экспериментально было показано, что одни и те же физиологические сдвиги могут сопровождать разные эмоциональные переживания. Другими словами, физиологические сдвиги имеют слишком неспецифический характер и потому сами по себе не могут определять качественное своеобразие и специфику эмоциональных переживаний. Кроме того, вегетативные изменения в организме человека обладают определенной инертностью, т.е. могут протекать медленнее и не успевать следовать за той гаммой чувств, которые человек способен иногда переживать почти одномоментно (например, страх и гнев или страх и радость).

Таламическая теория Кеннона-Барда. Эта теория в качестве центрального звена, ответственного за переживание эмоций, выделила одно из образований глубоких структур мозга - таламус (зрительный бугор). Согласно этой теории, при восприятии событий, вызывающих эмоции, нервные импульсы сначала поступают в таламус, где потоки импульсации делятся: часть из них поступает в кору больших полушарий, где возникает субъективное переживание эмоции (страха, радости и др.). Другая часть поступает в гипоталамус, который, как уже неоднократно говорилось, отвечает за вегетативные изменения в организме. Таким образом, эта теория выделила как самостоятельное звено субъективное переживание эмоции и соотнесла его с деятельностью коры больших полушарий. (см. рис.)

Таламическая теория Кеннона-Барда. Эта теория в качестве центрального звена, ответственного за переживание эмоций, выделила одно из образований глубоких структур мозга - таламус (зрительный бугор). Согласно этой теории, при восприятии событий, вызывающих эмоции, нервные импульсы сначала поступают в таламус, где потоки импульсации делятся: часть из них поступает в кору больших полушарий, где возникает субъективное переживание эмоции (страха, радости и др.). Другая часть поступает в гипоталамус, который, как уже неоднократно говорилось, отвечает за вегетативные изменения в организме. Таким образом, эта теория выделила как самостоятельное звено субъективное переживание эмоции и соотнесла его с деятельностью коры больших полушарий. (см. рис.)

Активационная теория Линдсли. Центральную роль в обеспечении эмоций в этой теории играет активирующая ретикулярная формация ствола мозга. Активация, возникающая в результате возбуждение нейроновретикулярной формации, выполняет главную эмоциогенную функцию. Согласно этой теории, эмоциогенный стимул возбуждает нейроны ствола мозга, которые посылают импульсы к таламусу, гипоталамусу и коре. Таким образом, выраженная эмоциональная реакция возникает при диффузной активации коры с одновременным включением гипоталамических центров промежуточного мозга. Основное условие появления эмоциональных реакций — наличие активирующих влияний из ретикулярной формации при ослаблении коркового контроля за лимбической системой. Предполагаемый активирующий механизм преобразует эти импульсы в поведение, сопровождающееся эмоциональным возбуждением. Эта теория, разумеется, не объясняет всех механизмов физиологического

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 4. PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY OF EMOTIONAL NEEDS AREA

Часть 2 Glossary - 4. PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY OF EMOTIONAL NEEDS AREA

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychophysiology

Terms: Psychophysiology