Lecture

Our mental world is diverse and versatile. Due to the high level of development of our psyche, we can and can do a lot. In turn, mental development is possible because we retain the acquired experience and knowledge. Everything that we learn, each pasha's experience, impression or movement leaves a certain trace in our memory that can persist for quite a long time and, under appropriate conditions, manifest itself again and become the subject of consciousness. Therefore, by memory we understand the recording, preservation, subsequent recognition and reproduction of traces.

past experience. It is through memory that people are able to accumulate information without losing their previous knowledge and skills. It should be noted that memory occupies a special place among the mental cognitive processes. Many researchers have characterized memory as a “cross-cutting” process that ensures the continuity of mental processes and unites all cognitive processes into a single whole.

How do mnemic processes proceed? For example, when we see a thing that we have previously perceived, we will recognize it. The subject seems familiar to us, famous. The consciousness that the object or phenomenon being perceived at the moment was perceived in the past is called recognition.

However, we can not only recognize objects. We can evoke in our consciousness the image of an object, which at the moment we do not perceive, but perceive it before. This process - the process of recreating the image of the object, which we perceived earlier, but not perceived at the moment, is called reproduction. Not only objects perceived in the past are reproduced, but also our thoughts, experiences, desires, fantasies, etc.

A necessary prerequisite for recognition and reproduction is the imprinting, the memorization of what was perceived, as well as its subsequent preservation.

Thus, memory is a complex mental process consisting of several private processes connected with each other. Memory is necessary for a person - it allows him to accumulate, save and subsequently use his personal life experience; knowledge and skills are stored in it .

Memory - a form of mental reflection, consisting in consolidating, preserving and subsequently reproducing traces of past experience

Memory connects the past of the subject with its present and future and is the most important cognitive function underlying development and learning.

Memory is the basis of mental activity. Without it, it is impossible to understand the basics of the formation of behavior, thinking, consciousness, subconsciousness. It should be noted that memory occupies a special place among the mental cognitive processes. Many researchers have characterized memory as a “cross-cutting” process that ensures the continuity of mental processes and unites all cognitive processes into a single whole.

|

Memory allows a person to accumulate and subsequently use personal life experience; knowledge and skills are stored in it. |

The physiological basis of memory is the plasticity of the nervous system. The plasticity of the nervous system is expressed in the fact that each neuro-cerebral process leaves a trail behind itself , changing the nature of further processes and determining the possibility of their recurrence when the stimulus acting on the senses is absent.

Psychological science faces a number of complex tasks related to the study of memory processes:

studying how traces are imprinted, what are the physiological mechanisms of this process, what conditions contribute to this imprint, what are its boundaries, what techniques can allow to expand the volume of the imprinted material. In addition, there are other questions that need to be answered. For example, how long these traces can be stored, what are the mechanisms for storing traces for short and long periods of time, what are the changes that traces of memory that are in a latent (latent) state and how these changes affect the flow of human cognitive processes.

In the history of psychology, attempts to explain the connection of mental processes during memorization and reproduction have been made since ancient times. Even Aristotle tried to deduce the principles according to which our ideas can communicate with each other. These principles, later called the principles of association (the word "association" means "connection", "connection"), are widely used in psychology. These principles are:

1. Association for contiguity. Images of perception or any ideas cause those ideas that in the past were experienced simultaneously with them or immediately after them. For example, the image of our school friend may recall events from our lives that have a positive or negative emotional tint.

2. Association by affinity. Images of perception or certain representations evoke in our consciousness representations similar to them in some way. For example, when you see a portrait of a person,

about himself. Or another example: when we see a thing, it can remind us of a person or a phenomenon.

3. Association by contrast. Images of perception or certain representations evoke in our consciousness representations in any respect opposed to them, contrasting with them. For example, by presenting something black, we can thereby evoke some image of white color in the representation, and by presenting a giant, we can thereby evoke the image of a dwarf in the representation.

The existence of associations is connected with the fact that objects and phenomena are really impressed and reproduced not in isolation from each other, but in connection with each other (in the words of Sechenov, “in groups or in rows”). The reproduction of some entails the reproduction of others, which is conditioned by the real objective connections of objects and phenomena. Under their influence, temporary connections arise in the cerebral cortex, which serve as the physiological basis of memory and reproduction.

The doctrine of association has been widely adopted in psychology, especially in the so-called associative psychology, which extended the principle of association to all mental phenomena (D. Hume, U. Jam, G. Spencer). Representatives of this scientific field overestimated the importance of associations, which led to a somewhat distorted view of many mental phenomena, including memory. Thus, memorization was considered as the formation of associations, and reproduction as the use of already existing associations. A special condition for the formation of associations is the repeated repetition of the same processes in time.

Unfortunately, in most cases, theories of associative psychology are a variant of the mechanistic interpretation of psychic phenomena. In the understanding of associationists, mental processes are connected, united with each other themselves, regardless of our awareness of the essential internal connections of the objects and phenomena themselves, the reflection of which these mental processes are.

However, it is impossible to deny the existence of associative links. However, a truly scientific substantiation of the principle of associations and the disclosure of their laws was given by I. M. Sechenov and I. P. Pavlov. According to Pavlov, an association is nothing more than a temporary connection, resulting from the simultaneous or sequential action of two or more stimuli. It should be noted that at present most researchers consider associations only as one of the phenomena of memory, and not as the main, and even more so its only mechanism.

The study of memory was one of the first sections of psychological science, where the experimental method was applied. Back in the 80s. XIX century. The German psychologist G. Ebbingauz proposed a method by which, as he believed, it was possible to study the laws of "pure" memory, independent of the activity of thinking. This technique - memorizing meaningless syllables. As a result, he derived the main curves for memorizing (remembering) the material and revealed a number of features of the manifestation of the mechanisms of associations. So, for example, he found that relatively simple events that made a strong impression on a person

can be memorized immediately, firmly and permanently. At the same time, a person can experience more complex, but less interesting events dozens of times, but they do not last long in his memory. Mr. Ebbingauz also found that with close attention to an event, it is enough to have his one-time experience to reproduce it precisely in the future. Another conclusion was that when memorizing a long row, the material at the ends is better reproduced (“edge effect”). One of the most important achievements of G. Ebbingauz was the discovery of the law of forgetting. This law was derived by him on the basis of experiments with memorizing meaningless three-letter syllables. During the experiments, it was found that after the first unmistakable repetition of a series of such syllables, forgetting goes very quickly at first. Already during the first hour, up to 60% of all information received is forgotten, and after six days less than 20% of the total number of syllables originally learned remain in memory.

In parallel with the studies of G. Ebbinghaus, studies were also conducted by other scientists. In particular, the famous German psychiatrist E. Krepelin studied how memorization proceeds in the mentally ill. Another well-known German scientist - psychologist G. E. Muller - carried out a fundamental study of the basic laws of fixing and reproducing traces of memory in humans. It should be noted that at first the study of human memory processes was mainly limited to the study of special conscious mnemonic activity (the process of deliberate memorization and reproduction of the material) and much less attention was paid to analyzing the natural mechanisms of tracing, which are equally manifested as in humans, so in the animal. This was due to the widespread introspective method in psychology. However, with the development of an objective study of the behavior of animals, the field of memory study has been significantly expanded. So, in the late XIX - early XX century. there were studies of the American psychologist E. Thorndike, who for the first time made the subject of learning the development of animal skills.

In addition to the theory of associations, there were other theories addressing the problem of memory. So, the gestalt theory replaced the associative theory . The initial concept in this theory was not the association of objects or phenomena, but their original, integral organization - the gestalt. According to supporters of this theory, memory processes are determined by the formation of a gestalt.

Apparently, it should be clarified that “gestalt” in Russian means “whole”, “structure”, “system”. This term was proposed by representatives of the direction that arose in Germany in the first third of the 20th century. Within the framework of this direction, a program of studying the psyche was put forward from the point of view of integral structures (gestalts), therefore this direction in psychological science became known as Gestalt psychology. The main postulate of this area of psychology says that the systemic organization of the whole determines the properties and functions of the parts that form it. Therefore, exploring memory, supporters of this theory proceeded from the fact that, both in memorization and reproduction, the material with which we are dealing acts as an integral structure, rather than a random set of elements that did not exist on an associative basis, as structural psychology interprets ( Wundt, E. B. Titchener). The dynamics of remembering and

|

|

Names

Ebbingauz Herman (1850-1909) - German psychologist, is considered one of the founders of experimental psychology. He was fascinated by the Fechner psychophysical research. As a result, he was able to realize the idea of quantitative and experimental study of not only the simplest mental processes, such as sensations, but also of memory. The source material for these studies was the so-called meaningless syllables - artificial combinations of speech elements (two consonants and a vowel between them), which do not cause any semantic associations. Having compiled a list of 2300 meaningless syllables, Ebingaus experimentally, and on himself, studied the processes of memorization and forgetting, having developed methods that made it possible to establish the peculiarities and laws of memory. He derived the "forgetting curve", which shows that the largest percentage of material is forgotten in the period immediately following memorization. This curve acquired the value of a sample, according to the type of which further development curves of skill, problem solving, etc. were built. The experimental studies of memory were reflected in the book “On Memory” (1885).

Ebingaus also has a number of important works on experimental psychology, including the work on the phenomenology of visual perception. He paid a lot of attention to studying the mental abilities of children, for this he developed a test that now bears his name ..

reproduction from the position of Gestalt psychology was conceived as follows. Some state that is relevant at a given moment in time creates a certain attitude in a person to memorize or reproduce. The corresponding installation enlivens in the mind some integral structures, on the basis of which, in turn, the material is remembered or reproduced. This setting controls the course of memorization and playback, determines the selection of the necessary information.

It should be noted that in those studies where attempts were made to conduct experiments from the position of Gestalt psychology, many interesting facts were obtained. Thus, the studies of B.V. Zeigarnik showed that if the subjects were offered a series of tasks, some allowing them to complete, and others interrupt unfinished, then the subjects recalled incomplete tasks twice as often as completed by the time of the interruption. This phenomenon can be explained as follows. Upon receipt of the task, the subject has a need to complete it. This need, which K. Levin called quasi- need, is heightened in the process of completing the task. It turns out to be realized when the task is completed, and remains unsatisfied if the task is not completed. Consequently, motivation affects the selectivity of memory, while preserving traces of unfinished tasks.

However, it should be noted that, despite certain successes and achievements, Gestalt psychology was unable to give an informed answer to the most important questions of the study of memory, namely the question of its origin. Representatives of two other directions: behaviorism and psychoanalysis could not answer this question either.

Representatives of behaviorism in their views turned out to be very close to as-socionists. The only difference was that behaviourists emphasized the role of reinforcement in memorizing material. They proceeded from the statement that for successful memorization it is necessary to back up the process of memorization with some kind of stimulus.

In turn, the merit of representatives of psychoanalysis is that they have revealed the role of emotions, motives and needs in memorizing and forgetting. Thus, they found that the events that have a positive emotional tint are reproduced most easily in our memory, and vice versa, negative events are quickly forgotten.

At about the same time, G. e. At the beginning of the 20th century, a semantic theory of memory arises . Representatives of this theory argued that the work of the relevant processes is directly dependent on the presence or absence of semantic related, combining the memorized material into more or less extensive semantic structures. The most prominent representatives of this direction were A. Binet and K. Buhler, who proved that, when memorizing and reproducing, the semantic content of the material comes to the fore.

A special place in the study of memory is occupied by the problem of studying the higher arbitrary and conscious forms of memory, which allow a person to consciously apply the techniques of mnemonic activity and arbitrarily turn to any segments of his past. It should be noted that for the first time philosopher-idealists drew attention to the existence of such an interesting problem, who, trying to describe these phenomena, opposed them to natural forms of memory and considered them to be a manifestation of higher conscious memory. Unfortunately, these attempts of idealist philosophers did not become the subject of special scientific research. Psychologists either talked about the role that they play in remembering an association, or pointed out that the laws of mind memorization are significantly different from the elementary laws of memorization. The question of the origin, and even more so about the development of higher forms of memory in man, was almost not at all raised.

For the first time, the eminent domestic psychologist L. S. Vygotsky conducted a systematic study of higher forms of memory in children, which in the late 1920s. He began to study the development of higher forms of memory and, together with his students, showed that higher forms of memory are a complex form of mental activity, social in origin. In the framework of the theory of the origin of higher mental functions proposed by Vygotsky, the stages of phylogenetic and ontogenetic memory development, including voluntary and involuntary, as well as direct and indirect memory, were singled out.

It should be noted that the works of Vygotsky were a further development of the research of the French scientist P. Jean, who was one of the first to treat memory as a system of actions oriented towards memorizing, processing and storing material. It was the French psychological school that proved the social conditionality of all the processes of memory, its direct dependence on the practical activity of man.

Russian psychologists continued to study the most complex forms of arbitrary mnemonic activity in which memory processes were associated

with thinking processes. Thus, the studies of A. A. Smirnov and P. I. Zinchenko, conducted from the standpoint of the psychological theory of activity, made it possible to uncover the laws of memory as meaningful human activity, established the dependence of memorization on the task and singled out the basic techniques of memorizing complex material. For example, Smirnov found that actions are remembered better than thoughts, and among actions, in turn, those that are associated with overcoming obstacles are more firmly remembered.

Despite real advances in psychological studies of memory, the physiological mechanism for capturing traces and the nature of memory itself have not been fully studied. Philosophers and psychologists of the late XIX - early XX century. limited only by pointing out that memory is a "common property of matter." By the 40th years. XX century. in Russian psychology, the opinion has already been formed that memory is a function of the brain, and the physiological basis of memory is the plasticity of the nervous system. The plasticity of the nervous system is expressed in the fact that each neuro-cerebral process leaves a trail behind itself , changing the nature of further processes and determining the possibility of their recurrence when the stimulus acting on the senses is absent. The plasticity of the nervous system is manifested in relation to mental processes, which is reflected in the emergence of connections between processes. As a result, one mental process can cause another.

In the last 30 years, studies have been conducted that showed that the printing, preservation and reproduction of traces are associated with deep biochemical processes, in particular with RNA modification, and that traces of memory can be transferred by humoral, biochemical means. Intensive studies of the so-called “reverberation of excitations, which have been considered as a physiological memory substrate , have begun. A whole system of research emerged in which the process of gradually consolidating (consolidating) the tracks was carefully studied. In addition, research has emerged in which an attempt was made to isolate areas of the brain that are necessary to preserve traces, and neurological mechanisms that underlie memorization and forgetting.

Despite the fact that many issues remain unresolved in the study of memory, psychology now has extensive material on this issue. Today there are many approaches to the study of memory processes. In general, they can be considered multilevel, because there are theories of memory that study this most complex system of mental activity at the psychological, physiological, neural and biochemical levels. And the more complex the memory system being studied, the more naturally the more difficult the theory is, trying to find the mechanism underlying it.

In this chapter, we have already become acquainted with individual psychological theories of memory. Now let's try to understand the meaning of neural and biochemical theories of memory.

At present, there is an almost complete consensus that permanent storage of information is associated with chemical or structural changes in the brain. Virtually everyone agrees that memorization is done through electrical activity, i.e. chemical or structural

changes in the brain should affect electrical activity and vice versa. You may ask: what is the relationship between electricity and the brain? As you remember, in the previous chapters it was noted that the nerve impulse is inherently electric. If we assume that memory systems are the result of electrical activity, then, therefore, we are dealing with nerve circuits that implement memory traces. Imagine that an electrical impulse from an activated neuron passes from the cell body through the axon to the body of the next cell. The place where the axon touches the next cell is called the synapse. On a separate cellular body there can be thousands of synapses, and all of them are divided into two main types: excitatory and inhibitory.

At the level of the excitatory synapse, the transfer of excitation to the next neuron occurs, and at the level of the inhibitory one, it is blocked. In order for a neuron to discharge, a rather large number of pulses may be required — one pulse, as a rule, is not enough. Therefore, the neuron excitation mechanism and excitation transfer to another cell is itself rather complicated. Imagine that a nerve impulse arriving at an excitatory synapse ultimately triggered a cell response. Where will the impulse from the newly excited cell go? It is quite logical to assume that it is easiest for him to return to the neuron whose impulse was the activation of a new cell. Then the simplest chain providing memory is a closed loop. Excitement consistently goes around the whole circle and starts a new one. This process is called reverb.

Consequently, the incoming sensory signal (signal from the receptors) causes a sequence of electrical pulses that persists indefinitely after the signal ceases. However, you should be aware that in practice the nerve chain containing traces of memory is much more complicated. This is confirmed by the fact that we forget certain information. Apparently, the reverberant activity caused by the signal actually cannot continue indefinitely. What leads to the termination of the reverb?

First, a genuine reverb chain must be much more difficult. Groups of cells are organized in a more complex way than the connection between two nerve cells. The background activity of these neurons, as well as the effects of numerous external inputs with respect to this loop, ultimately violate the nature of the circulation of pulses. Secondly, another possible mechanism for stopping reverberation is the emergence of new signals that can actively slow down the preceding reverberant activity. Third, the possibility of some unreliability of the neural circuits themselves is not excluded: the impulse arriving at one link of the chain is not always able to cause activity in the next link, and in the end the flow of impulses dies away. Fourthly, the reverberation may cease due to any "chemical" fatigue in neurons and synapses.

On the other hand, we have information that persists throughout our lives. Therefore, there must be mechanisms to ensure the preservation of this information. According to one popular theory, repeated electrical activity in neural circuits causes chemical activity.

or structural changes in the neurons themselves, which leads to the emergence of new neural circuits. This chain change is called consolidation. Trail consolidation takes a long time. Thus, the basis of long-term memory is the constancy of the structure of neural circuits.

However, it should be noted that, despite years of research, we still do not have a complete picture of the physiological mechanisms of memory. The problem of the physiology of memory is an independent problem that physiologists who study the brain are trying to solve. We will focus on that part of the problem that psychologists are investigating.

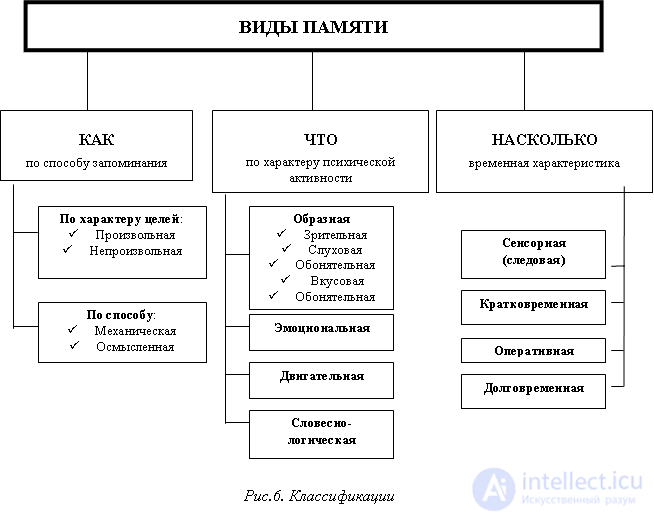

Существует несколько основных подходов в классификации памяти. В настоящее время в качестве наиболее общего основания для выделения различных видов памяти принято рассматривать зависимость характеристик памяти от особенностей деятельности по запоминанию и воспроизведению. При этом отдельные виды памяти вычленяются в соответствии с тремя основными критериями: 1) по характеру психической активности, преобладающей в деятельности, память делят на двигательную, эмоциональную, образную и словесно-логическую; 2) по характеру целей деятельности — на непроизвольную и произвольную; 3) по продолжительности закрепления и сохранения материала (в связи с его ролью и местом в деятельности) — на кратковременную, долговременную и оперативную (рис. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1. Классификация основных видов памяти

|

It is interesting

Как происходит кодирование и сохранение информации в памяти In modern psychology, there are three main classifications of memory. The first of these is associated with three stages of memory: encoding, storage and reproduction. In the second type of memory are allocated for short-term or long-term storage of information. According to the third classification, there are different types of memory depending on the content of stored information (for example, one memory system is for facts, the other is for skills). For each of these classifications, there are data showing that distinguishable entities — say, short-term and long-term memory — are mediated by different brain structures. Very interesting data were obtained in brain scans, in which neuroanatomical differences between coding and reproduction stages were studied. The experiments consisted of two parts. In the first part, devoted to coding, the subjects memorized a set of verbal elements, such as pairs, consisting of the name of the category and its private specimen (furniture — a sideboard). In the second part, devoted to reproduction, the subjects had to recognize or recall these elements according to the category name presented. In both parts of the experiment, brain activity was measured using a PET scan during the execution of the task by the subjects. The most remarkable result was that during coding, most of the activated brain areas were in the left hemisphere, and during playback, most of these areas were in the right hemisphere. Thus, the distinction between coding and reproduction has a clear biological basis. The course of the mnemonic process has different specifics depending on how long the material needs to be remembered, for a few seconds or for a longer period. It is said that in situations of the first kind, short-term memory works, and in situations of the second kind - long-term memory.

|

The classification of types of memory according to the nature of mental activity was first proposed by P. P. Blonsky. Although all four types of memory allocated by him (motor, emotional, figurative and verbal-logical) do not exist independently of each other, and moreover, are in close interaction, Blonsky was able to identify the differences between different types of memory.

There are several basic approaches in the classification of memory. Individual types of memory are singled out in accordance with three main criteria: 1) according to the nature of mental activity,, memory is divided into motor, emotional, figurative, and verbal-logical; 2) according to the method of activity - on involuntary and arbitrary; 3) by the method of memorization - on a mechanical and meaningful one; 4) for the duration of fixing and preserving the material) - for short-term, long-term and operational (Fig. 5).

1) Motor (or motor) memory is the memorization, preservation and reproduction of various movements. Motor memory is the basis for the formation of various practical and labor skills, as well as the skills of walking, writing, etc.

2) Emotional memory is a memory for feelings. This kind of memory is our ability to memorize and reproduce feelings. Memories of experienced feelings - suffering, the joys of love accompany a person throughout his life. Emotional attitude to information, emotional background significantly affects memorization.

3) Figurative memory is a memory for ideas, pictures of nature and life, as well as sounds, smells, tastes, etc. The essence of figurative memory is that what is perceived is then reproduced in the form of representations. Many researchers divide figurative memory into visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory.

4) Verbal-logical memory is expressed in the memorization and reproduction of our thoughts. This is a memory for concepts, formulas, signs, thoughts. We memorize and reproduce the thoughts that have arisen in the process of thinking, thinking, remember the content of a read book, a conversation with friends. A feature of this type of memory is that thoughts do not exist without language, therefore the memory of them is called not just logical, but verbal-logical

1) Involuntary memorization and reproduction is carried out without special volitional efforts, when goals, tasks of memorizing or reproducing material are not set, it is carried out as if by itself. Involuntarily remembers much of what a person faces in life.

2) Arbitrary memorization is accompanied by voluntary attention, it is focused, it is selective. Memorization includes the logical methods of organizing the material, comprehending the memorized material.

The effectiveness of arbitrary memory depends on the purpose of memorization and on the methods of memorization .

Methods of learning: a) logical retelling, which includes: logical understanding of the material, systematization, the selection of the main logical components of information, retelling in their own words; b) figurative receptions of memorization (translation of information into images, graphics, schemes, pictures) - a figurative memory works; c) memory memorial techniques (special techniques to facilitate memorization).

1) Mechanical memorization is memorization without awareness of the logical connection between the various parts of the material being perceived. An example of such memorization is memorization of statistical data, historical dates, etc.

2) Meaningful memorization is based on an understanding of the internal logical connections between individual parts of the material. Therefore, meaningful memorization is always associated with the processes of thinking.

|

It is proved that the efficiency of meaningful memorization is 20 times higher than the mechanical one. |

Mechanical memorization is uneconomical, requires many repetitions. A mechanically learned person cannot always remember to the place and time. Meaningful memorization requires much less time and effort from a person, but is more effective.

With mechanical memorization, only 40% of the material remains after one hour, only 20% after a few hours, and in the case of meaningful memorization, 40% of the material is stored in memory even after 30 days.

1) Sensory (trace), or direct memory ensures the preservation of the perceived image for fractions of a second.

2) Short-term memory is a type of memory characterized by a very brief saving of perceived information (about 20 seconds) after a single short perception and immediate reproduction. Short-term memory plays a big role in human life. Thanks to it, a significant amount of information is processed, the unnecessary information is immediately eliminated and remains potentially useful. As a result, there is no overload of long-term memory. The volume of short-term memory is individual. It characterizes the natural memory of man and is preserved, as a rule, throughout his life. The volume of short-term memory is characterized by the ability to mechanically, i.e., without using special techniques, to memorize the perceived information.

In general, short-term memory is of great importance for the organization of thinking, and in this it is very similar to operational memory.

3) Operative memory refers to mnemonic processes that serve actual actions and operations that are directly performed by a person. It represents the synthesis of long-term and short-term memory. When we perform any complex action, such as arithmetic, we perform it in parts. At the same time, we keep “in mind” some intermediate results as long as we deal with them. As you move toward the end result, the specific “waste” material may be forgotten.

4) Secondary , or long-term memory - long-term preservation of information (starting from 20 seconds and extending to hours, months, years) after repeated repetition and reproduction. Only what was once in short-term memory can penetrate into long-term and be permanently deposited; therefore, short-term memory acts as a kind of filter that passes only the necessary, already selected information into long-term memory. At the same time, the transition of information from short-term to long-term memory is associated with a number of features. Thus, the last five or six units of information obtained through the senses mainly fall into short-term memory. In the long-term memory, you can transfer much more information than the individual amount of short-term memory allows. This is achieved by repeating the material to be remembered.

Consider the characteristics of these four types of memory.

motor (or motor) memory is the memorization, preservation and reproduction of various movements. Motive memory is the basis for the formation of various practical and labor skills, as well as the skills of walking, writing, etc. Without movement memory, we would have to learn to perform appropriate actions every time. However, when reproducing movements, we do not always repeat them exactly to the same form as before. There is undoubtedly some variation in them, a deviation from the initial movements. But the general nature of the movements still remains. For example, such stability of movements, regardless of circumstances, is characteristic of letter movements (handwriting) or of some of our motor habits: how we give a hand, welcoming our acquaintance, how we use cutlery, etc.

The most accurate movements are reproduced in the conditions in which they were performed earlier. In completely new, unusual conditions, we often reproduce

|

It is interesting

obtained in experiments with rats and other animal species. In some experiments, one group of rats was damaged by the hippocampus and the surrounding cortex, and another group was damaged by a completely different area in the anterior cortex. Then both groups of rats had to perform a task with a delayed reaction: in each sample, one stimulus was first presented (say, square), and then, after some time, the second stimulus (for example, a triangle); the animal should only respond if the second stimulus was different from the first. How well the animal coped with this task depended on the nature of the brain damage it had suffered and the length of the delay interval between stimuli. With a long delay (15 s and more), animals with a damaged hippocampus did not cope well with the task, and with damage to the anterior part of the cortex, it was relatively normal. Since a long delay between stimuli requires long-term memory to store the first stimulus, these results are consistent with the idea of the decisive role of the hippocampus in long-term memory. With a small delay between two stimuli (only a few seconds), the opposite happens: now animals with damaged bark do not cope with the task, and animals hippocampal damage is relatively good. Since, with a small delay between stimuli, the first of them should be stored in short-term memory, these results show that areas of the frontal cortex participate in short-term memory. So, short-term and long-term memory are realized by different parts of the brain. For a long time, psychologists did not divide the long-term memory into its individual types. It was assumed, for example, that the same long-term memory is used to store information about who is now in charge of the state, and to store cycling skills. New data showed that this is incorrect. Today, memory researchers identify three types of memory. A memory in which a person consciously recalls the past of an event, and this memory is experienced as occurring in a specific place and time, is usually called explicit. The following type of long-term memory is associated with skills. Such a memory is called implicit. The third type of memory - short-term memory. By; R. Atkinson, R. Atkinson, E. E. Smith, et al. Introduction to psychology: A textbook for universities / Trans. from English under. ed. V.P. Zinchenko. - M .: Trivola, 1999

|

we harass movements with great imperfection. It is not difficult to repeat the movements if we are accustomed to performing them using a certain tool or with the help of some specific people, and in the new conditions we have been deprived of this opportunity. It is also very difficult to repeat the movements, if they were previously part of some complex action, but now they must be reproduced separately. All this is explained by the fact that the movements are reproduced not by us in isolation from what they were previously connected with, but only on the basis of the connections already formed.

Motive memory in a child occurs very early. Its first manifestations relate to the first month of life. Initially, it is expressed only in motor conditioned reflexes, developed in children already at this time. Later memorization and reproduction of movements begin to take on a conscious character, closely associating with the processes of thinking, will, and others. It should be noted that by the end of the first year of life, the motor memory reaches the level of development required for speech mastery.

It should be noted that the development of motor memory is not limited to the period of infancy or the first years of life. The development of memory occurs at a later time. Thus, the motor memory in preschool children reaches a level of development that allows them to perform finely coordinated

actions related to mastering written language. Therefore, at different stages of development, the manifestation of motor memory is qualitatively inhomogeneous.

Emotional memory is a memory for feelings. This kind of memory is our ability to memorize and reproduce feelings. Emotions always signal how our needs and interests are being met, how our relations with the outside world are being realized. Therefore, emotional memory is very important in the life and activities of each person. Experienced and stored feelings act as signals, either encouraging to action, or restraining from actions that have caused negative experiences in the past.

It should be noted that the reproduced, or secondary, feelings may differ significantly from the original. This can be expressed both in a change in the power of feelings, and in a change in their content and character.

The strength of the reproduced feeling may be weaker or stronger than the primary one. For example, grief is replaced by sadness, and delight or strong joy - calm satisfaction; in the other case, the offense suffered earlier, with the recollection of it, becomes aggravated, and the anger increases. '

Significant changes can occur in the content of our feelings. For example, what we used to experience as an annoying misunderstanding, may eventually be reproduced as an amusing event, or that event that was spoiled by minor annoyances, eventually begins to be remembered as very pleasant.

The first manifestations of memory in a child are observed by the end of the first six months of life. At this time, the child can rejoice or cry at the mere sight of what had previously given him pleasure or suffering. However, the initial manifestations of emotional memory are significantly different from later ones. This difference lies in the fact that if in the early stages of a child’s development, emotional memory is conditional-reflex, then at higher levels of development, emotional memory is conscious.

A figurative memory is a memory for representations, pictures of nature and life, as well as sounds, smells, tastes, etc. The essence of figurative memory is that what is perceived earlier is then reproduced in the form of representations. When characterizing a figurative memory, one should keep in mind all those features that are characteristic of representations, and above all their pallor, fragmentation and instability. These characteristics are also inherent in this type of memory, so the reproduction of what was perceived before often disagrees with its original. And over time, these differences can significantly deepen ***.

The deviation of ideas from the original image of perception can go in two ways: the mixing of images or the differentiation of images. В первом случае образ восприятия теряет свои специфические черты и на первый план выступает то общее, что есть у объекта с другими похожими предметами или явлениями. Во втором случае черты, характерные для данного образа, в воспоминании усиливаются, подчеркивая своеобразие предмета или явления.

Особо следует остановиться на вопросе о том, от чего зависит легкость воспроизведения образа. Отвечая на него, можно выделить два основных фактора. Во-первых, на характер воспроизведения влияют содержательные особенности образа, эмоциональная окраска образа и общее состояние человека в момент восприятия. Так, сильное эмоциональное потрясение может вызвать даже галлюцинаторное воспроизведение виденного. Во-вторых, легкость воспроизведения во многом зависит от состояния человека в момент воспроизведения. Припоминание виденного наблюдается в яркой образной форме чаще всего во время спокойного отдыха после сильного утомления, а также в дремотном состоянии, предшествующем сну.

Точность воспроизведения в значительной мере определяется степенью задействования речи при восприятии. То, что при восприятии было названо, описано словом, воспроизводится более точно.

Следует отметить, что многие исследователи разделяют образную память на зрительную, слуховую, осязательную, обонятельную, вкусовую. Подобное разделение связано с преобладанием того или иного типа воспроизводимых представлений.

Образная память начинает проявляться у детей примерно в то же время, что и представления, т. е. в полтора-два года. Если зрительная и слуховая память обычно хорошо развиты и играют ведущую роль в жизни людей, то осязательную, обонятельную и вкусовую память в известном смысле можно назвать профессиональными видами памяти. Как и соответствующие ощущения, эти виды памяти особенно интенсивно развиваются в связи со специфическими условиями деятельности, достигая поразительно высокого уровня в условиях компенсации или замещения недостающих видов памяти, например, у слепых, глухих и т. д.

Словесно -логическая память выражается в запоминании и воспроизведении наших мыслей. Мы запоминаем и воспроизводим мысли, возникшие у нас в процессе обдумывания, размышления, помним содержание прочитанной книги, разговора с друзьями.

Особенностью данного вида памяти является то, что мысли не существуют без языка, поэтому память на них и называется не просто логической, а словесно-логической. При этом словесно-логическая память проявляется в двух случаях: а) запоминается и воспроизводится только смысл данного материала, а точное сохранение подлинных выражений не требуется; б) запоминается не только смысл, но и буквальное словесное выражение мыслей (заучивание мыслей). Если в последнем случае материал вообще не подвергается смысловой обработке, то буквальное заучивание его оказывается уже не логическим, а механическим запоминанием.

Оба этих вида памяти могут не совпадать друг с другом. Например, есть люди, которые хорошо запоминают смысл прочитанного, но не всегда могут точно и прочно заучить материал наизусть, и люди, которые легко заучивают наизусть, но не могут воспроизвести текст «своими словами».

Развитие обоих видов словесно-логической памяти также происходит не параллельно друг другу. Заучивание наизусть у детей протекает иногда с большей легкостью, чем у взрослых. В то же время в запоминании смысла взрослые, наоборот, имеют значительные преимущества перед детьми. Это объясняется тем, что при запоминании смысла прежде всего запоминается то, что является наиболее существенным, наиболее значимым. В этом случае очевидно, что выделение существенного в материале зависит от понимания материала, поэтому взрослые легче, чем дети, запоминают смысл. И наоборот, дети легко могут запомнить детали, но гораздо хуже запоминают смысл.

In the verbal-logical memory, the second role is assigned to the second signaling system, since verbal-logical memory is a specifically human memory, unlike the motor, emotional and figurative, which are also characteristic of animals in the simplest forms. Based on the development of other types of memory, verbal-logical memory becomes the leading one in relation to them, and the development of all other types of memory largely depends on the level of its development.

We have already said that all types of memory are closely related to each other and do not exist independently of each other. For example, when we master any kind of motor activity, we rely not only on motor memory, but also on all other types of memory, because in the process of mastering activity we remember not only movements, but also explanations given to us, our experiences and impressions. Therefore, in each specific process, all types of memory are interrelated.

There is, however, such a division of memory into species, which is directly related to the peculiarities of the activity itself. Thus, depending on the goals of activity, memory is divided into involuntary and arbitrary. In the first case, it means memorization and reproduction, which is carried out automatically, without the will of the person, without control from the side of consciousness. In this case, there is no special goal to remember or recall something, that is, there is no special mnemonic task. In the second case, such a task is present, and the process itself requires willful effort.

Involuntary memorization is not necessarily weaker than arbitrary. On the contrary, it often happens that involuntarily memorized material is reproduced better than material that was specially memorized. For example, an involuntarily heard phrase or perceived visual information is often memorized more reliably than if we tried to memorize it on purpose. Involuntarily memorized material that is in the spotlight, and especially when it is associated with a certain mental work.

There is also a division of memory into short-term and long-term. Short-term memory is a type of memory characterized by a very brief preservation of the perceived value. From one point of view, short-term memory is somewhat similar to involuntary. As in the case of involuntary memory, in the case of short-term memory, special mnemic techniques are not used. But unlike involuntary, with short-term memory, we make certain volitional efforts to memorize.

The manifestation of short-term memory is the case when the subject is asked to read words or provide very little time for memorizing them (about one minute), and then they are asked to immediately reproduce what he has memorized. Naturally, people differ in the number of words remembered. This is because they have a different amount of short-term memory.

The volume of short-term memory is individual. It characterizes the natural memory of man and is preserved, as a rule, throughout his life. The volume of short-term memory is characterized by the ability to mechanically, i.e., without using special techniques, to memorize the perceived information.

Short-term memory plays a very large role in human life. Thanks to it, a significant amount of information is processed, the unnecessary information is immediately eliminated and remains potentially useful. As a result, there is no overload of long-term memory. In general, short-term memory is of great importance for the organization of thinking, and in this it is very similar to operational memory.

The concept of operative memory refers to mnemic processes that serve actual actions and operations that are directly carried out by a person. When we perform any complex action, such as arithmetic, we perform it in parts. At the same time, we keep “in mind” some intermediate results as long as we deal with them. As you move toward the end result, the specific “waste” material may be forgotten. We observe a similar phenomenon when performing any more or less complex action. Parts of the material with which the person operates may be different (for example, the child begins to read with the folding of letters). The volume of these parts, the so-called operational units of memory, significantly affects the success of a particular activity. Therefore, the formation of optimal operational units of memory is of great importance for memorizing material.

Without a good short-term memory, the normal functioning of long-term memory is impossible. Only what used to be in short-term memory can penetrate into the latter for a long time, therefore short-term memory acts as a kind of buffer that passes only the necessary, already selected information into long-term memory. At the same time, the transition of information from short-term to long-term memory is associated with a number of features. Thus, the last five or six units of information obtained through the senses mainly fall into short-term memory. The translation from short-term memory into long-term one is carried out thanks to a volitional effort. And in the long-term memory, you can transfer information much more than the individual amount of short-term memory allows. This is achieved by repeating the

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization, preservation, reproduction, recognition

Часть 2 10.3.1 Memory Specifications - 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization, preservation,

Часть 3 Sample Questions and Answers - 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization,

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology