Lecture

Representations of ancient and medieval philosophers about the soul and mind . Life psychology as the basis of pre-scientific psychological knowledge. Idealistic and materialistic views of ancient philosophers. The controversy about the primacy of the material and intangible. Mechanistic materialism of Democritus. Sensations as a result of "interaction of the atoms of the soul and the atoms of the surrounding things." The doctrine of the soul of Aristotle. The concept of "entelechy". Moral and ethical aspects of the doctrine of the soul of Socrates and Plato. Cartesian philosophy and dualism of R. Descartes.

Introspection method and the problem of self-observation . Two sources of knowledge in the teachings of John. Locke on reflection. Introspective psychology. The essence of introspective observation. The first experimental psychological laboratory Wundt. A modern understanding of the role and place of methods of self-observation and observation and psychology.

Behaviorism as a science of behavior . The main provisions of the teachings of J. Watson on the psychology of behavior. The idea of human behavior as a system of reactions in the views of behaviorists. Experimental studies in the framework of behaviorism. "Intermediate variables" in the theory of E. Tolmepa. Phenomena of instrumental, or operant, conditional reactions in the teachings of E. Thorndike and B. Skinner. The value of behaviorism for the development of modern psychology.

The formation of domestic psychology. The development of psychological thought in Russia in the XVIII century. Psychological views of M, V. Lomonosov. The development of domestic psychology in the XIX century. The work of I. M. Sechenov "Reflexes of the brain" and its importance for the development of Russian psychology. The role of the works of I. P. Pavlov for the development of psychological thought in Russia. Contribution A.F. Lazursky, II. Ii. Lapge, G.I. Chelianov in the development of Russian psychology at the turn of the 19th - 20th centuries. The formation of Soviet psychology. Psychological schools of S. L. Rubinstein, L. S. Vygotsky, A. R. Luria. The works of Soviet psychologists in the 1930s – 60s Modern psychological schools in Russia.

The relationship of psychology and modern sciences. Psychology and philosophy. Epistemology. The interpenetration of psychology and sociology. The relationship and contradiction of pedagogy and psychology. General idea of pedology. Resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) "On pedological distortions in the system of the People's Commissariat of Education" (1936) and its consequences for the development of psychological science in Russia. The relationship of psychology and history. Historical method. The role and place of psychology in the development of technical sciences. Connection of psychology with medical and biological sciences.

The main branches of psychology, fundamental and applied branches of psychology. General psychology, its subject and tasks. Formation and formation of the main branches of psychology. Works by S. L. Rubinstein, F. Galton, V. Stern, W. McDougall and E. Ross. Applied branches of psychology.

2.1. Representations of ancient and medieval philosophers about the soul and mind

Psychology, like any other science, has passed a certain path of development. The famous psychologist of the late XIX - early XX century. Mr. Ebbinghaus was able to speak about psychology very briefly and accurately - psychology has a huge background and very short history.

rotary story. History refers to the period in the study of the psyche, which was marked by a departure from philosophy, convergence with the natural sciences and the emergence of its own experimental methods. This happened in the second half of the XIX century, but the origins of psychology are lost in the depths of the centuries.

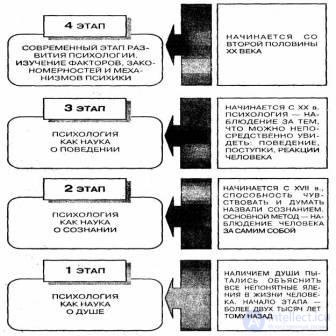

In this chapter we will not consider the history of psychology. There is a whole training course dedicated to such a complex and interesting problem. Our task is to show how a person’s perception of mental phenomena has changed in the process of historical development and how, at the same time, the subject of psychological research has changed. From this point of view in the history of psychology can be divided into four stages. At the first stage, psychology existed as a science of the soul, at the second - as a science of consciousness, at the third - as a science of behavior, and at the fourth - as a science of the psyche (Fig. 2.1). Consider in more detail each of them.

The peculiarity of psychology as a scientific discipline is that a person faces manifestations of the psyche since he began to realize himself as a man. However, mental phenomena for a long time remained an incomprehensible mystery to him. For example, the idea of the soul as a special substance, separate from the body, is deeply rooted in the people. Such an opinion was formed in people because of the fear of death, since even primitive man knew that people and animals were dying. At the same time, the human mind was not able to explain what happens to a person when he dies. At the same time, primitive people already knew that when a person sleeps, that is, he does not come into contact with the outside world, he sees dreams — incomprehensible images of a non-existent reality. Probably, the desire to explain the relationship of life and death, the interaction of the body and a certain unknown intangible world led to the emergence of the belief that man consists of two parts: the tangible, that is, the body, and the intangible, that is, the soul. From this point of view, life and death could be explained by the state of unity of soul and body. While a person is alive, his soul is in the body, and when it leaves the body, the person dies. When a person sleeps, the soul leaves the body for a while and is transferred to some other place. Thus, long before mental processes, properties, states became the subject of scientific analysis, people tried to explain their origin and content in a form that was accessible to themselves.

A lot of time has passed since then, but even now a person cannot fully explain many mental phenomena. For example, so far the mechanisms of interaction between the psyche and the organism are an unsolved mystery. Nevertheless, during the existence of mankind there was an accumulation of knowledge about mental phenomena. There was the emergence of psychology as an independent science, although initially psychological knowledge accumulated at the household or everyday level.

Everyday psychological information obtained from public and personal experience, form pre-scientific psychological knowledge, due to the need to understand another person in the process of working together, living together, to respond correctly to his actions and actions. This knowledge can contribute to orientation in the behavior of others. They may be correct, but in general they are devoid of systematicity, depth, evidence. It is likely that the desire of a person to understand himself led

40 • Part I. Introduction to General Psychology

Fig. 2.1. The main stages of the development of psychological science

to the formation of one of the first sciences - philosophy. It was within this science that the nature of the soul was considered. Therefore, it is not by chance that one of the central questions of any philosophical trend is related to the problem of the origin of a person and his spirituality. Namely - what comes first: the soul, the spirit, that is, the ideal, or the body, matter. The second, no less significant, question of philosophy is the question of whether it is possible to know the reality around us and the person himself.

Depending on how philosophers answered these basic questions, and all can be attributed to certain philosophical schools and directions. It is customary to single out two main directions in philosophy: idealistic and materealistic. Ideal philosophers believed that the ideal is primary, and matter is secondary. First there was spirit, and then matter. Materialistic philosophers, on the contrary, said that matter is primary, and the ideal is secondary. (It should be noted that such a division of philosophical trends is characteristic of our time. Initially, there was no division into materialistic and idealistic philosophy. The division was based on belonging to a particular school of philosophy, which answered the basic question of philosophy in different ways. For example, the Pythagorean school , Milesian school, the philosophical school of the Stoics, etc.)

The name of the science we study translates as "science of the soul." Therefore, the first psychological views were associated with religious beliefs of people. This viewpoint is largely reflected by the position of idealist philosophers. For example, in the ancient Egyptian treatise "Monument of Memphis Theology" (end of IV millennium BC), an attempt is made to describe the mechanisms of the psychic. According to this work, the organizer of everything that exists, the universal architect is the god Ptah. Whatever people may think or say, he knows their hearts and tongues. However, already in those ancient times there was the idea that mental phenomena are somehow connected with the human body. In the same ancient Egyptian work, the following interpretation of the meaning of the sense organs for man is given: the gods "created the eyes sight, the hearing of the ears, the breath of the nose, so that they would give a message to the heart." At the same time, the heart was assigned the role of a conductor of consciousness. Thus, along with the idealistic views on the nature of the human soul, there were others - materialistic, which from the ancient Greek philosophers acquired the most distinct expression.

The study and explanation of the soul is the first stage in the development of psychology. But to answer the question of what a soul is, it was not so easy. Representatives of idealistic philosophy view the psyche as something primary, existing independently, independently of matter. They see in mental activity a manifestation of an immaterial, disembodied and immortal soul, and all material things and processes are interpreted either as our sensations and representations, or as some mysterious manifestation of “absolute spirit”, “world will”, “ideas”. Such views are quite understandable, since idealism was born when people, practically without any idea of the structure and functions of the body, thought that mental phenomena are the activity of a special, supernatural being - the soul and spirit, which infuses into a person at birth and leaves him at the time of sleep and death.

Initially, the soul was represented as a special subtle body or creature living in different organs. With the development of religious views, the soul began to be understood as a kind of twin body, as an incorporeal and immortal spiritual essence associated with the "other world", where it dwells forever, leaving the person. On this basis, various idealistic systems of philosophy emerged, which asserted that ideas, spirit, consciousness are primary, the beginning of everything that exists, and nature, matter — secondary, derived from spirit, ideas, consciousness. The most prominent representatives of this direction are the philosophers of the school of Pythagoras from the island of Ego. Pythagorean school

42 Part I. Introduction to Psychology

Names

Aristotle (384-322 BC) is an ancient Greek philosopher, who is rightly considered the founder of psychological science. In his treatise “On the Soul,” he, integrating the achievements of ancient thought, created an integral psychological system. In his opinion, the soul cannot be separated from the body, because it is its form, the way of its organization. At the same time, Aristotle singled out three souls in his teaching: plant, animal, and rational, or human, of divine origin. He explained this division by the degree of development of mental functions. The lower functions ("feeding") are peculiar to plants, and the highest - to man.

Along with this, Aristotle divided the senses into five digits. In addition to the bodies that transmit the individual sensory qualities of things, he singled out a “common sensibility”, which allows one to perceive properties that are common to many objects (for example, magnitude ).

In his writings (“Ethics”, “Rhetoric”, “Metaphysics”, “The History of Animals”), he tried to explain many mental phenomena, including he tried to explain the mechanisms of human behavior by the desire to realize internal activity, coupled with a sense of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. In addition, Aristotle made a great contribution to the development of ideas about human memory and thinking.

preached the doctrine of the eternal circulation of souls, that the soul is attached to the body in the order of punishment. This school was not just a religious, but was a religious and mystical union. According to the views of the Pythagoreans, the universe has not a real, but an arithmetic-geometric structure. In everything that exists, from the movement of celestial bodies to grammar, harmony reigns, having a numerical expression. Harmony is also inherent in the soul - the harmony of the opposites of the body.

The materialistic understanding of the psyche differs from the idealistic views in that from this point of view the psyche is a secondary phenomenon derived from matter. However, the first representatives of materialism were very far in their interpretations of the soul from modern ideas about the psyche. Thus, Heraclitus (530-470 BC), following the philosophers of the Milesian school - Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes - speaks about the material nature of mental phenomena and the unity of soul and body. According to his teaching, all things are modifications of fire. Everything that exists, including physical and mental, is constantly changing. In the microcosm of the body, the general rhythm of fire transformations throughout the cosmos is repeated, and the fiery principle in the body is the soul - psyche. The soul, according to Heraclitus, is born by evaporation from moisture and, returning to a damp state, dies. However, between the state of "humidity" and "fieriness" there are many transitions. For example, about a drunken man, Heraclitus says, "that he does not notice where he is going, because his psyche is wet." On the contrary, the soul is drier, the wiser it is.

We also encounter the idea of fire as the basis of the existing world in the works of another well-known ancient Greek thinker Democritus (460–370 BC), who developed the atomistic model of the world. According to Democritus, the soul is

This material substance, which consists of atoms of fire, spherical, light and very mobile. Democritus tried to explain all the mental phenomena by physical and even mechanical reasons. So, in his opinion, human sensations arise because the atoms of the soul are set in motion by atoms of air or atoms directly “flowing out” from objects. From the foregoing it follows that the materialism of Democritus was of a naive, mechanistic nature.

We encounter much more complex concepts about the soul in the views of Aristotle (384-322 BC). His treatise “On the Soul” is the first specially psychological work, which for a long time remained the main guide in psychology, and Aristotle himself can rightly be considered the founder of psychology. He denied looking at the soul as a substance. At the same time, he did not consider it possible to treat the soul in isolation from matter (living bodies), as the idealist philosophers did. The soul, according to Aristotle, is an expediently functioning organic system. To determine the nature of the soul, he used a complex philosophical category - “entelechy,” “... the soul,” he wrote, “is necessary to have an essence in the sense of the form of a natural body that has life in its ability. The essence (as a form) is entelechy; therefore, the soul is the entelechy of such a body. " Acquainted with the dictum of Aristotle, unwittingly I want to ask about the meaning of the concept of "entelechy". To which Aristotle gives the following answer: "If the eye were a living being, then his soul would be the sight." So, the soul is the essence of the living body, just as sight is the essence of the eye as an organ of sight. Consequently, the main essence of the soul, according to Aristotle, is the realization of the biological existence of the organism.

Subsequently, the concept of "soul" more and more narrowed to reflect mainly ideal, "metaphysical" and ethical problems of human existence. The foundations of such an understanding of the soul were probably laid in ancient India. Thus, in the texts of the Vedas (II millennium BC), the problem of the soul was discussed primarily as ethical. It was argued that in order to achieve bliss, it is necessary to improve the personality through correct behavior. Later, we encounter ethical problems of spiritual development in the religious teachings of Jainism and Buddhism (6th century BC). However, the most clearly ethical aspects of the soul were first revealed by a disciple of Socrates (470–399 BC) - Plato (427–347 BC). In the works of Plato outlined the view of the soul as an independent substance. In his opinion, the soul exists along with the body and independently of it. The soul is the beginning invisible, sublime, divine, eternal. The body is the beginning of a visible, base, transient, perishable. Soul and body are in a complex relationship. By its divine origin, the soul is called to control the body. However, sometimes the body, torn apart by various desires and passions, takes over the soul. В этих взглядах Платона ярко выражен его идеализм. Из своего представления о душе Платон и Сократ делают этические выводы. Душа — самое высокое, что есть в человеке, поэтому он должен заботиться о ее здоровье значительно больше, чем о здоровье тела. При смерти душа расстается с телом, и в зависимости от того, какой образ жизни вел человек, его душу ждет различная судьба: либо она будет блуждать вблизи земли, отягощенная земными элементами, либо отлетит от земли в идеальный мир.

Давайте попробуем ответить на вопрос: насколько прав или не прав Платон? Существует ли тот мир, о котором он писал и говорил? Отвечая на этот вопрос профессор Ю. Б. Гиппенрейтер в своей книге «Введение в общую психологию» пишет, что в какой-то степени Платон прав. Этот мир действительно существует! Это мир духовной человеческой культуры, зафиксированный в ее материальных носителях, прежде всего в языке, в научных и литературных текстах. Это мир абстрактных понятий, в которых отражены общие свойства и сущности вещей. И на конец, самое главное, это мир человеческих ценностей и идеалов, это мир человеческой морали. Таким образом, идеалистические воззрения Сократа и Платона раскрыли другую сторону человеческой психики — морально-этическую. Поэтому с полной уверенностью можно говорить о том, что идеалистические учение Сократа и Платона не менее важны для современной психологической науки, чем взгляды материалистов. Особенно отчетливо это наблюдается в последние десятилетия, когда духовные аспекты жизни человека стали интенсивно обсуждаться в психологии в связи с такими понятиями, как зрелость личности, здоровье личности, рост личности и др. Вряд ли современная психология была бы той наукой, какая она есть сейчас, если бы не было идеалистических учений античных фило-софов о душе с их этическими следствиями.

Следующий крупный этап развития психологии связан с именем французского философа Рене Декарта (1569-1650). Латинский вариант его имени— Ренатус Картезиус. Декарт считается родоначальником рационалистической философии. Согласно его представлениям, знания должны строиться на непосредственно очевидных данных, на непосредственной интуиции. Из нее они должны выводиться методом логического рассуждения. Данная позиция известна в научном мире как «картезианская философия», или «картезианская интуиция».

Исходя из своей точки зрения, Декарт считал, что человек с детства впитывает в себя очень многие заблуждения, принимая на веру различные утверждения и идеи. Поэтому для того, чтобы найти истину, по его мнению, сначала надо все подвергнуть сомнению, в том числе и достоверность информации, получаемой органами чувств. В таком отрицании можно дойти до того, что и Земли не существует. Что же тогда остается? Остается наше сомнение — верный признак того, что мы мыслим. Отсюда и известное выражение, принадлежащее Декарту «Мыслю — значит, существую». Далее, отвечая на вопрос «Что же такое мысль?», он говорит, что мышление — это «все то, что происходит в нас», все то, что мы «воспринимаем непосредственно само собою». В этих суждениях заключается основной постулат психологии второй половины XIX в. — постулат о том, что первое, что обнаруживает человек в самом себе, — это его сознание.

Однако в своих трудах Декарт доказывал, что не только работа внутренних органов, но и поведение организма — его взаимодействие с другими внешними телами — не нуждается в душе. По его мнению, взаимодействие организма с внешней средой осуществляется посредством нервной машины, состоящей из мозга как центра и нервных «трубок». Внешние предметы действуют на периферические окончания расположенных внутри «нервных» трубок, нервных «нитей», последние, натягиваясь, открывают клапаны отверстий, ведущих из мозга в нервы, по каналам которых «животные духи» устремляются в соответствующие мышцы, которые в результате «надуваются». Таким образом, по мнению Декарта, причина поведенческой активности человека лежит вне его и определяется внешними факторами, а сознание не принимает участия в регуляции поведения. Поэтому в своем учении он резко противопоставляет душу и тело, утверждая, что существуют две независимые друг от друга субстанции — материя и дух.

В истории психологии это учение получило название «дуализм» (от лат. dualis — «двойственный»). С точки зрения дуалистов, психическое не является функцией мозга, его продуктом, а существует как бы само но себе, вне мозга, никак не завися от него. На почве дуалистических учений в психологии XIX в. получила широкое распространение идеалистическая теория так называемого психофизического параллелизма, утверждающая, что психическое и физическое существуют параллельно: независимо друг от друга, но совместно. Основными представителями этого направления в психологии являются В. Вундт, Г. Эббингауз, Г. Спенсер, Т. Рибо, А. Вине и У. Джеме.

Примерно с этого времени возникает и новое представление о предмете психологии. Способность думать, чувствовать, желать стали называть сознанием. Таким образом, психика была приравнена к сознанию. На смену психологии души пришла психология сознания. Однако сознание еще долго рассматривали отдельно от всех других естественных процессов. Философы по-разному трактовали сознательную жизнь, считая ее проявлением божественного разума или результатом субъективных ощущений. Но всех философов-идеалистов объединяло общее убеждение в том, что психическая жизнь — это проявление особого субъективного мира, познаваемого только в самонаблюдении и недоступного ни для объективного научного анализа, ни для причинного объяснения. Такое понимание получило очень широкое распространение, а подход стал известен под названием интроспективной трактовки сознания.

На протяжении длительного времени метод интроспекции был не просто главным, а единственным методом психологии. Он основан на двух утверждениях, развиваемых представителями интроспективной психологии: во-первых, процессы сознания «закрыты» для внешнего наблюдения, но, во-вторых, процессы сознания способны открываться (репрезентироваться) субъекту. Из этих утверждений следует, что процессы сознания конкретного человека могут быть изучены только им самим и никем более.

Идеологом метода интроспекции был философ Дж. Локк (1632-1704), который развил тезис Декарта о непосредственном постижении мыслей. Дж. Локк утверждал, что существует два источника всех знаний: объекты внешнего мира и деятельность нашего собственного ума. На объекты внешнего мира человек направляет свои внешние чувства и в результате получает впечатления о внешних вещах, а в основе деятельности ума лежит особое внутреннее чувство — рефлексия. Локк определял ее как «наблюдение, которому ум подвергает свою деятельность».

В то же время под деятельностью ума Локк понимал мышление, сомнение, веру, рассуждения, познание, желание.

Дж. Локк заявлял, что рефлексия предполагает особое направление внимания на деятельность собственной души, а также достаточную зрелость субъекта. У детей рефлексии почти нет, они заняты в основном познанием внешнего мира. Однако рефлексия может не развиться и у взрослого, если он не проявит склонности к размышлению над собой и не направит на свои внутренние процессы специального внимания. Исходя из данного положения, можно говорить о том, что Локк считает возможным раздвоение психики. Психические процессы, по его мнению, протекают на двух уровнях. К процессам первого уровня он относил восприятие, мысли, желания и т. д., а к процессам второго уровня — наблюдение, или «созерцание», этих мыслей и образов восприятия.

Другим не менее важным выводом из утверждения Дж. Локка является то, что, поскольку процессы сознания открываются только самому субъекту, ученый может проводить психологические исследования только над самим собой. При этом способность к интроспекции не приходит сама по себе. Для того чтобы овладеть этим методом, надо долго упражняться.

По сути, Дж. Локк, находясь на материалистических позициях, придерживается двух принципов английского материализма ХУ1-ХУП вв., который возник и развивался под влиянием достижений в механике и физике, и в первую очередь открытий Ньютона. Первый из провозглашенных английскими материалистами того времени принципов был принцип сенсуализма, чувственного опыта, как единственного источника познания. Второй — это принцип автоматизма, согласно которому задача научного познания психических, как и всех природных явлений, заключается в том, чтобы разложить все сложные явления на элементы и объяснить их, опираясь на связи между этими элементами.

Данная точка зрения получила название сенсуалистического материализма. Несмотря на некоторую ограниченность суждений, для своего времени эта позиция была весьма прогрессивна, а лежащие в ее основе принципы оказали огромное влияние на развитие психологической науки.

Параллельно с учением Дж. Локка в науке стало развиваться еще одно, близкое к нему течение — ассоциативное направление. Истоком этого учения являлся все тот же сенсуалистический материализм. Только если Дж. Локк больше внимания уделял первому принципу, то представители ассоциативного направления строили свои умозаключения на основе второго принципа. Возникновение и становление ассоциативной психологии было связано с именами Д. Юма и Д. Гартли.

The English doctor D. Gartley (1705-1757), opposing himself to the materialists, nevertheless laid the foundations of a materialistic in its spirit associative theory. The cause of psychic phenomena he saw in the vibration that occurs in the brain and nerves. In his opinion, the nervous system is a system subject to physical laws. Accordingly, the products of its activities were included in a strictly causal series, no different from the same in the external, physical world. This causal series encompasses the behavior of the whole organism — and the perception of vibrations in the external environment (the ether), and the vibrations of the nerves and medulla, and the vibrations of the muscles. The vibration theory he developed got its

further development in the works of D. Hume and served as the basis for the development of associative psychology.

David Hume (1711-1776) introduces an association as a fundamental principle . By association, he understands a certain attraction of representations, which establishes external mechanical connections between them. In his opinion, all complex formations of consciousness, including the consciousness of one’s “I,” as well as objects of the external world, are only “bundles of representations” united by external relations - associations. It should be noted that Hume was skeptical of Locke’s reflection. In his book, A Study on Human Knowledge, he writes that when we look at ourselves, we don’t get any impressions about substance, causality, or other concepts that seem to be derived, as Locke wrote, from reflection. The only thing we notice is the perceptual complexes that replace each other. Therefore, the only way to get information about the mental is experience. Moreover, by experience he understood impressions (sensations, emotions, etc.) and “ideas” - copies of impressions. Thus, the works of Hume to a certain extent predetermined the emergence of experimental methods of psychology.

It should be noted that by the middle of the XIX century. associative psychology was the mainstream. And it was in this direction at the end of the XIX century. The method of introspection has become very widely used. Passion for introspection was general. Moreover, grandiose experiments were conducted to test the method of introspection. This was facilitated by the conviction that introspection as a method of psychology has a number of advantages. It was believed that the causal relationship of mental phenomena is directly reflected in consciousness. Therefore, if you want to find out why you raised your hand, then the reason for this must be sought in your mind. In addition, it was believed that introspection, unlike our senses, which distort the information obtained in the study of external objects, provides psychological facts, so to speak, in a pure form.

However, over time, the widespread use of the method of introspection did not lead to the development of psychology, but, on the contrary, to a certain crisis. From the standpoint of introspective psychology, the mental is identified with consciousness. As a result of such an understanding, the consciousness became locked in itself, and consequently, a separation of the psychic from objective being and the subject itself was observed. Moreover, since it was argued that the psychologist can study himself, the psychological knowledge identified in the process of such a study did not find its practical application. Therefore, in practice, public interest in psychology has fallen. Psychology was interested only in professional psychologists.

At the same time, it should be noted that the period of domination of introspective psychology did not pass without a trace for the development of psychological science in general. At this time, a number of theories emerged that had a significant impact on the subsequent development of psychological thought. Among them:

• The theory of elements of consciousness, the founders of which were V. Wundt and E. Titchener;

• psychology of acts of consciousness, the development of which is associated with the name of F. Brentano;

• the theory of the stream of consciousness, created by W. James;

• theory of phenomenal fields;

• Descriptive psychology of V. Dilthey.

Common to all these theories is that in place of a real person, actively interacting with the outside world, put the consciousness in which the real human being dissolves.

It is impossible not to note the role of introspective psychology in the formation and development of experimental methods of psychological research. It is within the framework of introspective psychology in 1879. Wundt in Leipzig established the first experimental psychological laboratory. In addition, introspective psychology predetermined the emergence of other promising directions in the development of psychology. Thus, the impotence of the “psychology of consciousness” in front of many practical tasks arising from the development of industrial production, which required the development of tools to control human behavior, led to the fact that in the second decade of the 20th century. a new direction of psychology has emerged, the representatives of which declared a new subject of psychological science - it was not the psyche, not consciousness, but behavior, understood as an aggregate of observed, predominantly motor reactions from the outside. This direction was called "behaviorism" (from the English behavior - "behavior") and was the third stage in the development of ideas about the subject of psychology. But before proceeding to the consideration of psychology as a behavioral science, let us return to introspection and note the differences in attitude towards it from the position of psychology of consciousness and modern psychology. First of all, it is necessary to define the terms used.

Introspection literally means “self-observation”. In modern psychology, there is a method of using data from self-observation. There are a number of differences between these concepts. Firstly, by what is observed, and, secondly, by how the data obtained are used for scientific purposes. The position of representatives of introspective psychology is that observation is directed to the activity of one's mind and reflection is the only way to obtain scientific knowledge. This approach is due to the peculiar point of view of introspectionists on consciousness. They believed that consciousness has a dual nature and can be directed both to external objects and to the processes of consciousness itself.

The position of modern psychology on the use of data of self-observation is that self-observation is considered as a "monospection", as a method of comprehending the facts of consciousness, and the facts of consciousness, in turn, act as "raw material" for further understanding of mental phenomena. The term "monospection" means that consciousness is a single process. However, introspection as a self-observation of its internal state exists, but at the same time it is inseparable from “extraspection” - observation of external objects and behavior of people. Thus, self-observation is one of the methods of modern psychological science, which allows to obtain information that is the basis for the subsequent psychological analysis.

The founder of behaviorism, J. Watson, saw the task of psychology in the study of the behavior of a living being, adapting to its environment. And in the first place in the conduct of research in this area is the solution of practical problems arising from social and economic development. Therefore, in just one decade, behaviorism spread throughout the world and became one of the most influential areas of psychological science.

The emergence and spread of behaviorism was marked by the fact that completely new facts were introduced into psychology - behavioral facts that differ from the facts of consciousness in introspective psychology.

In psychology, behavior is understood as the external manifestations of human mental activity. And in this respect, behavior is opposed to consciousness as a combination of internal, subjectively experienced processes, and thus the facts of behavior in behaviorism and the facts of consciousness in introspective psychology are divorced according to the method of their identification. Some are detected by external observation, and others by self-observation.

In fairness it should be noted that in addition to practical orientation, due to rapid economic growth, the rapid development of behaviorism determined other reasons, the first of which can be called common sense. Watson believed that the actions and behavior of this person were the most important things in a man for the people around him. And he was right, because ultimately our experiences, the characteristics of our consciousness and thinking, that is, our mental individuality, are reflected in our actions and behavior as an external manifestation. But what cannot be agreed with Watson is that he, arguing the need to engage in the study of behavior, denied the need to study consciousness. Thus, Watson divided the mental and its external manifestation - behavior.

The second reason lies in the fact that, according to Watson, psychology must become a natural science discipline and introduce an objective scientific method. The desire to make psychology an objective and natural science discipline led to the rapid development of the experiment, based on principles different from the introspective methodology, which brought practical results in the form of economic interest in the development of psychological science.

As you already understood, the basic idea of behaviorism was based on the statement of the significance of behavior and the complete denial of the existence of consciousness and the need to study it. Watson wrote: “A behaviorist ... finds no proof of the existence of a stream of consciousness, so convincingly described by James, he considers only the existence of an ever-expanding flow of behavior”. From the point of view of Watson, behavior is a system of reactions. Reaction is another new concept that was introduced into psychology in connection with the development of behaviorism. Since Watson sought to make psychology natural science, it was necessary to explain the causes of human behavior from a natural science position. For Watson, the behavior or behavior of a person is explained

the presence of any effects on humans. He believed that there was not a single action beyond which there would be no reason in the form of an external agent or stimulus. This is how the famous "S - R" formula (stimulus – reaction) appeared. For behaviorists, the S-R ratio has become a unit of behavior. Therefore, from the point of view of behaviorism, the main tasks of psychology are as follows: identifying and describing types of reactions; study of the processes of their education; study of laws and> combinations, i.e. the formation of complex reactions. Behaviorists put forward the following two tasks as general and final tasks of psychology: to arrive at predicting the behavior (reaction) of a person according to the situation (stimulus) and, on the contrary, to determine or describe the stimulus that caused it by the nature of the reaction.

The solution of the tasks was carried out by behaviorists in two directions: theoretical and experimental. Creating the theoretical basis of behaviorism, Watson tried to describe the types of reactions and, above all, identified innate and acquired reactions. Among the congenital reactions, he attributes those behavioral acts that can be observed in newborn babies, namely sneezing, hiccuping, sucking, smiling, crying, movement of the torso, limbs, head, etc.

It should be noted that if Watson did not have serious difficulties with the description of congenital reactions, since it is enough to observe the behavior of newborns, then with the description of the laws by which congenital reactions are acquired, things were worse. To solve this problem, he needed to push off from any of the already existing theories, and he turned to the works of IP Pavlov and V. M. Bekhterev. Their works contained a description of the mechanisms for the emergence of conditioned, or, as they said at the time, “combined” reflexes. After reviewing the work of Russian scientists, Watson takes the concept of conditioned reflexes as the natural science base of his psychological theory. He says that all new reactions are acquired by conditioning.

In order to understand the mechanism of conditioning, consider the following example. Mother strokes the child, and a smile appears on his face. After a while, the appearance of the mother in front of the child makes him smile, even if the mother does not stroke him. Why? This phenomenon, according to Watson, is due to the following: stroking is an unconditional stimulus, and a smile on a child’s face is an unconditional innate reaction. But before each such contact, the face of the mother appeared, which was a neutral conditioned stimulus. The combination of unconditional and neutral stimuli for a certain time led to the fact that over time the effect of the unconditioned stimulus turned out to be unnecessary. In order for the child to smile, one neutral stimulus, in this case the face of the mother, was enough for him.

In this example, we are faced with a simple unconditional reaction of the child. But how does a complex reaction form? By forming a complex of unconditional reactions, Watson answers this question. For example, one unconditional stimulus causes a definite unconditional reaction, another - the second unconditional reaction, and another one - the third unconditional reaction. And when all three unconditioned stimuli are replaced by one conditional stimulus, then later upon exposure to the conditioned stimulus, a complex set of reactions will be triggered.

|

|

Watson John Broadus (1878-1958) - American psychologist, the founder of behaviorism. Speaking against the views on psychological science as a science about directly experienced subjective phenomena, he proposed new approaches to the study of mental phenomena. He presented his point of view in a program article that was written in 1913. In contrast to introspective psychology, he proposed to rely solely on objective methods, the requirements for which were developed in the natural sciences, and as a subject of psychology he considered human behavior from birth to death. Accordingly, the main task of psychological research, according to Watson, is the prediction of behavior and control over it.

The views of Watson found their development in stimulus-reactive psychology. Within the framework of this trend, which did not take shape, however, into a single concept, some of the theories became widely known. Among them: the theory of operant reinforcement by B. F. Skinner, the principles of social learning by A. Bandura, and others.

Thus, all human actions, according to Watson, are complex values, or complexes, of reactions. It should be emphasized that at first glance Watson’s conclusions seem correct and not in doubt. A certain external influence in a person causes a definite response unconditional (innate) reaction or a complex of unconditional (innate) reactions, but this is only at first glance. In life, we are faced with phenomena that can not be explained from this point of view. For example, how to explain riding a bear on a bicycle in a circus? None of the unconditional or conditional stimuli can not cause a similar reaction or a complex of reactions, since riding a bicycle can not be classified as unconditional (innate) reactions. Unconditional reactions to light can be blinking, to the sound - startle, to the food stimulus - salivation. But no combination of such unconditional reactions will lead to the fact that the bear will ride a bicycle.

No less significant for behaviorists was the conduct of experiments, with the help of which they sought to prove the correctness of their theoretical conclusions. In this regard, Watson’s experiments to study the causes of fear have become widely known. He tried to find out what stimuli caused a fear reaction in a child. For example, Watson observed the reaction of the child during his contact with the mouse and the rabbit. The mouse did not cause a fear reaction, and the child was curious about the rabbit, he tried to play with him, take him in his arms. In the end, it was found that if you hit the iron bar very close to the child but with an iron bar, he would sob sharply and then burst into tears. So, it is established that a sharp blow with a hammer causes a fear reaction in a child. Then the experiment continues. Now the experimenter strikes the iron bar at the moment when the child takes the rabbit in his arms. After some time, the child comes to a state of anxiety only with one

the appearance of a rabbit. According to Watson, the conditioned reaction of fear appeared. заключение Дж. Уотсом показывает, как можно излечить ребенка от этого страх Он сажает за стол голодного ребенка, который уже очень боится кролика, и дает ему есть. Как только ребенок прикасается к еде, ему показывают кролика, но только издалека, через открытую дверь из другой комнаты, — ребенок продолжает есть. В следующий раз показывают кролика, также во время еды, немного ближе. Через несколько дней ребенок уже ест с кроликом на коленях.

Однако довольно скоро обнаружилась чрезвычайная ограниченность схемы « S — R » для объяснения поведения людей. Один из представителей позднего бихевиоризма Э. Толмен ввел в эту схему существенную поправку. Он предложил поместить между S и R среднее звено, или «промежуточные переменные» — V, в результате схема приобрела вид: « S - V - R ». Под «промежуточными переменными Э. Толмен понимал внутренние процессы, которые опосредуют действие стимула. К ним относились такие образования, как «цели», «намерения», «гипотезы», «познавательные карты» (образы ситуаций). И хотя промежуточные переменны» были функциональными эквивалентами сознания, выводились они как «конструкты», о которых следует судить исключительно по особенностям поведения и тем самым существование сознания по-прежнему игнорировалось.

Другим значимым шагом в развитии бихевиоризма было изучение особого типа условных реакций, которые получили название инструментальных, или оперантных. Явление инструментального, или операптного, обусловливания состоит в том, что если подкреплять какое-либо действие индивида, то оно фиксируется и воспроизводится с большей легкостью. Например, если какое-либо определенное действие постоянно подкреплять, т. е. поощрять или вознаграждать кусочком сахара, колбасы, мяса и т. п., то очень скоро животное будет выполнять это действие при одном лишь виде поощрительного стимула.

Согласно теории бихевиоризма, классическое (т. е. павловское) и оперантное обусловливания являются универсальным механизмом научения, общим и для животного и для человека. При этом процесс научения представлялся как вполне автоматический, не требующий проявления активности человека. Достаточно использовать одно лишь подкрепление для того, чтобы «закрепить» в нервной системе успешные реакции независимо от воли или желаний самого человека. Отсюда бихевиористы делали выводы о том, что с помощью стимулов и подкрепления можно буквально «лепить» любое поведение человека, «манипулировать» им, что

поведение человека жестко «детерминировано» и зависит от внешних обстоятельств и собственного прошлого опыта.

Как мы видим, и в данном случае игнорируется существование сознания, т. е. игнорируется существование внутреннего психического мира человека, что само по себе, с нашей точки

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 2. Psychology in the structure of modern sciences

Часть 2 2.4. The formation of domestic psychology - 2. Psychology in

Часть 3 test questions - 2. Psychology in the structure of modern

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology