Lecture

Это продолжение увлекательной статьи про память.

...

material to be remembered. The result is an increase in the total amount of memorized material.

How memorization of material occurs and the basic processes of memory function, we will discuss in the next section.

Memorization. Memory, like any other cognitive mental process, has certain characteristics. The main characteristics of the memory are: volume, speed of capturing, accuracy of reproduction, duration of preservation, readiness to use the stored information.

Memory size is the most important integral characteristic of memory, which characterizes the possibilities of storing and saving information. Speaking

|

|

Names

Anatoly Alexandrovich Smirnov (1894-1980) is a well-known domestic psychologist, an expert in the field of memory psychology, as well as general, age and pedagogical psychology and history of psychology. In the period 1945-1972. He headed the Institute of Psychology of the USSR Academy of Pedagogical Sciences. In the process of research, he discovered the relationship between involuntary and voluntary memorization, revealed the relationship between memory and thinking. Experimentally proved that the nature of involuntary memorization is associated with the structure of the subject. The results of an experimental study of memory were reflected by him in a number of works: “The Psychology of Memorization” (1948), “Problems of the Psychology of Memory” (1966).

about the amount of memory, as an indicator using the number of memorized units of information.

Such a parameter, as the speed of reproduction, characterizes a person's ability to use the information he has in practical activity. As a rule, meeting the need to solve any problem or problem, a person turns to information stored in memory. At the same time, some people quite easily use their “information reserves”, while others, on the contrary, have serious difficulties in trying to reproduce the information necessary to solve even a familiar task.

Another characteristic of memory is fidelity. This characteristic reflects the ability of a person to accurately store, and most importantly, accurately reproduce the information captured in the memory. In the process of storing in memory a part of information is lost, and a part is distorted, and when reproducing this information a person may make mistakes. Therefore, the fidelity is a very significant characteristic of memory.

The most important characteristic of memory is duration, it reflects the ability of a person to retain the necessary information for a certain time. Very often in practice, we are faced with the fact that a person remembers the necessary information, but cannot save it for the necessary time. For example, a person is preparing for the exam. He remembers one educational topic, and when he starts learning the next one, he suddenly discovers that he does not remember what he had taught before. Sometimes it is different. The person remembered all the necessary information, but when it was required to reproduce it, he could not do it. However, some time later, he was surprised to note that he remembers everything he managed to learn. In this case, we are faced with another characteristic of memory - the readiness to reproduce the information captured in the memory.

As we have already noted, memory is a complex mental process that combines a number of mental processes. The listed characteristics of memory in one degree or another are inherent in all processes that are united by the concept of "memory". Acquaintance with the basic mechanisms and processes of memory, we begin with memorization.

Memorization is the process of capturing and saving the perceived information. According to the degree of activity of this process, it is customary to single out two types of memorization: unintentional (or involuntary) and intentional (or arbitrary).

Inadvertent memorization is memorization without a predetermined goal, without using any tricks and manifesting volitional efforts. This is a simple imprint of what impacted us and retained some trace of excitement in the cerebral cortex. For example, after a walk in the woods or after a visit to the theater, we can recall a lot of what we saw, although we did not specifically set ourselves the task of memorizing.

In principle, each process that occurs in the cerebral cortex due to external stimulus leaves traces, although their degree of strength varies. It is best remembered that which is vital for a person: everything that is connected with his interests and needs, with the goals and objectives of his activity. Therefore, even involuntary memorization, in a certain sense, is selective in nature and is determined by our attitude to the environment.

In contrast to involuntary memorization, arbitrary (or deliberate) memorization is characterized by the fact that a person sets a certain goal for himself - to memorize certain information - and uses special memorization techniques. Voluntary memorization is a special and complex mental activity subordinate to the task of remembering. In addition, voluntary memorization involves a variety of actions performed in order to better achieve the goal. Such actions, or methods of memorizing material, include memorization, the essence of which lies in the repeated repetition of educational material until its complete and unmistakable memorization. For example, verses, definitions, laws, 4'-formulas, historical dates, etc. are learned. It should be noted that, all other things being equal, arbitrary memorization is noticeably more productive than unintentional memorization.

The main feature of intentional memorization is the manifestation of volitional efforts in the form of setting the task of memorization. Repeated repetition allows you to reliably and firmly remember the material, many times greater than the amount of individual short-term memory. Much of what is perceived in life a large number of times is not remembered by us, if the task is not to remember. But if you set yourself this task and perform all the actions necessary for its realization, memorization proceeds with relatively great success and turns out to be quite strong. Illustrating the importance of setting the task for memorization, A. A. Smirnov cites as an example a case that occurred with the Yugoslav psychologist P. Radossavlevich. He conducted an experiment with a person who had a poor understanding of the language in which the experiment was conducted. The essence of this experiment was to memorize meaningless syllables. Usually, to remember them, it took several repetitions. At the same time, the subject read them 20, 30, 40 and, finally, 46 times, but did not give the experimenter a signal that he remembered them. When the psychologist asked to repeat the recited series by heart, the surprised subject, who did not understand because of insufficient knowledge

|

|

Names

Petr Ivanovich Zinchenko (1903-1969) - famous Russian psychologist, professor at Kharkov University. The greatest fame brought him to work on the study of memory. The first studies of P. I. Zinchenko were carried out in the 1930s. under the leadership of A. N. Leontiev. In subsequent studies focused on the study of involuntary memory. The main results of his memory research were reflected in his book “Involuntary Memorization”, 1961.

Under his leadership, the development of the problem of learning efficiency and memory productivity was carried out.

language of the purpose of the experiment, exclaimed: "How? So should I memorize him? ”Then he read a number of syllables indicated to him six more times and repeated it without error.

Therefore, in order to memorize as best you can, you must set a goal - not only to perceive and understand the material, but to really remember it.

It should be noted that when memorizing is of great importance, not only the formulation of a common task (remember what is perceived), but also the formulation of particular, special tasks. In some cases, for example, the task is to memorize only the essence of the material we perceive, only the main thoughts and the most essential facts, in others it is to memorize verbatim, in the third it is to accurately memorize the sequence of facts, etc.

Thus, the formulation of special tasks plays an essential role in memorization. Under its influence, the process of memorization can change. However, according to S. L. Rubinstein, memorization very much depends on the nature of the activity during which it is performed. Moreover, Rubinstein believed that it was impossible to make unambiguous conclusions about the greater effectiveness of voluntary or involuntary memorization. The advantages of voluntary memorization clearly appear only at first glance. Studies of the well-known Russian psychologist P. I. Zinchenko convincingly proved that the setting for memorization, making it the direct goal of the subject’s action, is not in itself decisive for the effectiveness of the memorization process. In certain cases, involuntary memorization may be more effective than arbitrary. In Zinchenko's experiments, the unintentional memorization of pictures in the course of an activity whose purpose was to classify them (without the task of memorizing) was definitely higher than in the case when the subject was tasked with specifically remembering the pictures.

A study by A. A. Smirnova on the same problem confirmed that involuntary memorization can be more productive than intentional: that the subjects memorized involuntarily, along the way, in the process of activity,

the purpose of which was not memorization, it was remembered more firmly than what they tried to memorize on purpose. The essence of the experiment was that the subjects were presented with two phrases, each of which corresponded to a spelling rule (for example, “My brother learns the Chinese language” and “we must learn to write in short phrases”). In the course of the experiment, it was necessary to establish which rule this phrase belongs to, and come up with another pair of phrases on the same topic. It was not required to memorize phrases, but after a few days, the subjects were asked to recall both those and other phrases. It turned out that the phrases that they had invented themselves in the process of active work were remembered about three times better than those that the experimenter gave them.

Consequently, memorization, included in any activity, proves to be the most effective, since it turns out depending on the activity during which it is performed.

It is remembered, as realized, first of all that which constitutes the goal of our action. However, what is not relevant to the goal of the action is remembered worse than in the case of arbitrary memorization directed specifically at this material. At the same time, it is still necessary to take into account that the vast majority of our systematic knowledge arises as a result of a special activity, the purpose of which is to memorize the relevant material in order to keep it in memory. Such activities aimed at memorizing and reproducing retained material are called mnemonic activities.

Mnemonic activity is a specifically human phenomenon, for only in humans does memorization become a special task, and memorizing material, preserving it in memory and recall is a special form of conscious activity. При этом человек должен четко отделить тот материал, который ему было предложено запомнить, от всех побочных впечатлений. Поэтому мнемическая деятельность всегда носит избирательный характер.

Следует отметить, что исследование мнемической деятельности человека является одной из центральных проблем современной психологии. Основными задачами изучения мнемической деятельности являются определение доступного человеку объема памяти и максимально возможной скорости запоминания материала, а также времени, в течение которого материал может удерживаться в памяти. Эти задачи не являются простыми, тем более что процессы запоминания в конкретных случаях имеют целый ряд различий.

Другой характеристикой процесса запоминания является степень осмысления запоминаемого материала. Поэтому принято выделять осмысленное и механическое запоминание.

Механическое запоминание — это запоминание без осознания логической связи между различными частями воспринимаемого материала. Примером такого запоминания является заучивание статистических данных, исторических дат и т. д. Основой механического запоминания являются ассоциации по смежности. Одна часть материала связывается с другой только потому, что следует за ней во времени. Для того чтобы установилась такая связь, необходимо многократное повторение материала.

В отличие от этого осмысленное запоминание основано на понимании внутренних логических связей между отдельными частями материала. Два положения,

из которых одно является выводом из другого, запоминаются не потому, что следуют во времени друг за другом, а потому, что связаны логически. Поэтому осмысленное запоминание всегда связано с процессами мышления и опирается главным образом на обобщенные связи между частями материала на уровне второй сигнальной системы.

Доказано, что осмысленное запоминание во много раз продуктивнее механического. Механическое запоминание неэкономно, требует многих повторений. Механически заученное человек не всегда может припомнить к месту и ко времени. Осмысленное же запоминание требует от человека значительно меньше усилий и времени, но является более действенным. Однако практически оба вида запоминания — механическое и осмысленное — тесно переплетаются друг с другом. Заучивая наизусть, мы главным образом основываемся на смысловых связях, но точная последовательность слов запоминается при помощи ассоциаций по смежности. С другой стороны, заучивая даже бессвязный материал, мы, так или иначе, пытаемся построить смысловые связи. Так, один из способов увеличения объема и прочности запоминания не связанных между собою слов состоит в создании условной логической связи между ними. В определенных случаях эта связь может быть бессмысленной по содержанию, но весьма яркой с точки зрения представлений. Например, вам надо запомнить ряд слов: арбуз, стол, слон, расческа, пуговица и т. д. Для этого построим условно-логическую цепочку следующего вида: «Арбуз лежит на столе. За столом сидит слон. В кармане его жилета лежит расческа, а сам жилет застегнут на одну пуговицу». And so on. С помощью такого приема в течение одной минуты можно запомнить до 30 слов и более (в зависимости от тренировки) при однократном повторении.

Если же сравнивать эти способы запоминания материала — осмысленное и механическое, — то можно прийти к выводу о том, что осмысленное запоминание намного продуктивней. При механическом запоминании в памяти через один час остается только 40 % материала, а еще через несколько часов — всего 20 %, а в случае осмысленного запоминания 40 % материала сохраняется в памяти даже через 30 дней.

Весьма отчетливо проявляется преимущество осмысленного запоминания над механическим при анализе затрат, необходимых для увеличения объема запоминаемого материала. При механическом заучивании с увеличением объема материала требуется непропорционально большое увеличение числа повторений. Например, если для запоминания шести бессмысленных слов требуется только одно повторение, то при заучивании 12 слов необходимо 14-16 повторений, а для 36 слов — 55 повторений. Следовательно, при увеличении материала в шесть раз необходимо увеличить количество повторений в 55 раз. В то же время при увеличении объема осмысленного материала (стихотворения), чтобы его запомнить, требуется увеличить количество повторений с двух до 15 раз, т. е. количество повторений возрастает в 7,5 раза, что убедительно свидетельствует о большей продуктивности осмысленного запоминания. Поэтому давайте более подробно рассмотрим условия, способствующие осмысленному и прочному запоминанию материала.

Осмысление материала достигается разными приемами, и прежде всего выделением в изучаемом материале главных мыслей и группированием их в виде плана. При использовании данного приема мы, запоминая текст, расчленяем его на более

or less distinct sections, or groups of thoughts. Each group includes that which has one common semantic core, a single theme. Closely related to this technique is the second way, which facilitates memorization: the allocation of semantic strongholds. The essence of this method is that we replace each meaningful part with a word or concept reflecting the main idea of the memorized material. Then, both in the first and in the second case, we unite the learned, consciously making a plan. Each item in the plan is a generalized heading for a specific part of the text. The transition from one part to the following parts is a logical sequence of basic thoughts of the text. When the text is reproduced, the material concentrates around the headings of the plan, and is tightened to them, which facilitates its recollection. The need to make a plan teaches a person to thoughtful reading, comparing individual parts of the text, clarifying the order and internal interrelation of issues.

It has been established that students who compose a plan when memorizing texts reveal more solid knowledge than those who memorized text without such a plan.

A useful technique for comprehending the material is a comparison, that is, finding similarities and differences between objects, phenomena, events, etc. One of the variants of this method is to compare the material under study with that obtained earlier. Thus, when studying with children a new material, the teacher often compares it with the one already studied, thereby including new material in the knowledge system. Similarly, material is compared with other information that has just been obtained. For example, it is easier to remember the dates of birth and death of M. Yu. Lermontov, if we compare them with each other: 1814. and 1841.

The clarification of the material and the rules with examples, the solution of problems in accordance with the rules, the conduct of observations, laboratory work, etc., also helps to comprehend the material. There are other methods of understanding.

The most important method of meaningful memorization of the material and the achievement of high strength of its preservation is the method of repetition. Repetition is the most important condition for mastering knowledge, skills and abilities. But to be productive, repetitions must meet certain requirements. Studies have revealed some patterns in the use of the method of repetition. First, learning is uneven:

following a rise in reproduction, there may be some decline. In this case, it is temporary, as new repetitions give a significant increase in recall.

Secondly, memorization comes in jumps. Sometimes a few repetitions in a row do not give a significant increase in recall, but then, with subsequent repetitions, there is a sharp increase in the amount of memorized material. This is explained by the fact that the traces left every time the object is perceived are not enough at first to recall, but then, after several repetitions, their effect is immediately apparent, and moreover in a large number of words.

Thirdly, if the material as a whole is not difficult to memorize, then the first repetitions give a greater result than the subsequent ones. Every new

repetition gives a very slight increase in the amount of memorized material. This results from the fact that the main, easier part is remembered quickly, and the remaining, more difficult part requires a large number of repetitions.

Fourthly, if the material is difficult, then memorization goes, on the contrary, at first slowly, and then quickly. This is due to the fact that the actions of the first repetitions due to the difficulty of the material are insufficient and the increase in the volume of the memorized material increases only with repeated repetitions.

Fifthly, repetition is needed not only when we learn the material, but also when it is necessary to fix in memory what we have already learned. With the repetition of a learned material, its strength and duration of preservation increase many times.

In addition to the above patterns of use of the repetition method, there are conditions conducive to improving the efficiency of remembering. It is very important that the repetition is active and diverse. To do this, the memorizer is given different tasks: to invent examples, answer questions, draw a diagram, draw up a table, make a visual aid, etc. With active repetition, connections are revitalized at the level of the second signal system, since the variety of repetition forms contributes to the formation of new connections material with practice. As a result, memorization is made more complete. Passive repetition does not give such an effect. In one experiment, students memorized texts by repeating fivefold. Analysis of the effectiveness of each reading showed that as soon as repetition acquires a passive character, learning becomes unproductive.

It is also very important to distribute the repetition in time correctly. In psychology, there are two ways to repeat: concentrated and distributed. In the first method, the material is learned in one step, repetition follows one after the other without interruption. For example, if it takes 12 repetitions to memorize a poem, a student reads it 12 times in a row until he learns it. With distributed repetition, each reading is separated from the other by some interval.

Conducted research shows that distributed repetition is more rational than concentrated repetition. It saves time and energy, contributing to a more solid assimilation of knowledge. In one study, two groups of students memorized a poem in different ways: the first group - concentrated, the second - distributed. Full memorization with the concentrated method required 24 repetitions, and with the distributed method only 10, that is, 2.4 times less. In this case, the distributed repetition provides a great strength of knowledge. Therefore, experienced teachers repeat with the students educational material for a whole year, but in order not to decrease the activity of children, they diversify the methods of repetition, include material in new and new connections.

Very similar to the distributed learning method is the playback method during memorization. Its essence consists in attempts to reproduce material that has not yet been fully learned. For example, you can learn the material in two ways:

a) restrict himself to reading and read as long as it is possible, until he is sure that he has learned; 6) read the material once or twice, then try to reproduce it, then read it again several times and try again

reproduce, etc. Experiments show that the second option is much more productive and more expedient. Learning is faster, and saving becomes more durable.

The productivity of memorization also depends on how memorization is carried out: in whole or in parts. In psychology, there are three ways of memorizing large-volume material: holistic, partial, and combined. The first method (holistic) is that the material (text, poem, etc.) is read from beginning to end several times, until complete assimilation. In the second method (partial), the material is divided into parts and each part is memorized separately. First, one part is read several times, then the second, then the third, and so on. The combined method is a combination of the whole and the partial. The material is first read entirely one or several times, depending on its size and nature, then difficult places are singled out and memorized separately, after which the whole text is read again. If the material, such as a poetic text, is large in size, it is divided into stanzas, logically complete parts, and memorization takes place in this way: first, the text is read one or two times from beginning to end, its general meaning becomes clear, then each part is memorized after which the material is again read in its entirety.

Research M. Shardakov showed that of these methods is the most appropriate is combined. It provides uniform memorization of all parts of the material, requires deep reflection, the ability to highlight the most important. Such activity is carried out with a greater concentration of attention, hence its greater productivity. In Shardakov's experiments, students who memorized the poem in a combined way required only 9 repetitions, while learning as a whole - 14 repetitions, and when learning by parts - 16 repetitions.

It should be noted that the success of memorization largely depends on the level of self-control. Manifestations of self-control are attempts to reproduce the material when learning it. Such attempts help to establish what we have memorized, what mistakes were made during playback, and what you should pay attention to in subsequent reading. In addition, the productivity of memorization depends on the nature of the material. Visual-shaped material is remembered better than verbal, and logically related text is reproduced more fully than scattered sentences.

There are certain differences in memorizing descriptive and explanatory texts. So, pupils of junior and middle classes memorize artistic passages and natural-science descriptions better, worse - socio-historical texts. At the same time, these differences are almost absent in high school.

Thus, for successful memorization, it is necessary to take into account the peculiarities of the mechanisms of the memorization process and to use various mnemic techniques. In conclusion, we schematically show the material presented. (fig. 10.2).

Saving, playback, recognition. All the information that has been perceived, we not only remember, but also save a certain time. Saving as a process of memory has its own laws. For example,

that persistence can be dynamic and static. Dynamic preservation is manifested in RAM, and static - in long-term. With dynamic preservation, the material changes little, with static, on the contrary, it necessarily undergoes reconstruction and certain processing.

Reconstruction of material stored by long-term memory is primarily influenced by new information, continuously coming from our senses. Reconstruction manifests itself in various forms, for example, in the disappearance of some less significant details and their replacement by other details, in a change in the sequence of the material, in the degree of its generalization.

Removing material from memory is carried out using two processes - reproduction and recognition. Reproduction is the process of recreating an image of an object that we perceived earlier, but not perceived at the moment. Reproduction differs from perception in that it is performed after it and beyond it. Thus, the physiological basis of reproduction is

Fig. 10.2. Memory mechanisms

There is a resumption of the neural connections formed earlier in the perception of objects and phenomena.

Like memorization, reproduction can be unintentional (involuntary) and intentional (arbitrary). In the first case, the reproduction happens unexpectedly for us. For example, passing by the school where we studied, we suddenly can reproduce the image of the teacher who taught us, or the images of school friends. A special case of unintentional reproduction is the appearance of persevering images, which are characterized by exceptional stability.

With arbitrary reproduction, as opposed to involuntary, we recall, having a deliberately set goal. Such a goal is the desire to remember something from our past experience, for example, when we set ourselves the goal to recall a well-learned poem. In this case, as a rule, the words "go by themselves."

There are cases when playback proceeds in the form of a more or less prolonged recall. In these cases, the achievement of the goal - to remember something - is carried out through the achievement of intermediate goals, allowing to solve the main task. For example, in order to remember an event, we try to recall all the facts that are to some extent connected with it. Moreover, the use of intermediate links is usually conscious . We deliberately outline what can help us remember, or think in what relation to it is what we are looking for, or evaluate everything that we remember, or judge why it does not fit, etc. Therefore, the processes recall is closely related to the processes of thinking.

However, recalling, we often encounter difficulties. At first, we remember not what we need, reject it and set ourselves the task of recalling something again. Obviously, all of this requires certain volitional efforts from us. Therefore, recall is at the same time a volitional process.

In addition to playback, we are constantly faced with the phenomenon of recognition. Recognition of an object occurs at the moment of its perception and means that the perception of an object occurs, an idea about which was formed in a person either on the basis of personal impressions (memory representation), or on the basis of verbal descriptions (imagination representation). For example, we recognize a house in which a friend lives, but in which we have never been, and recognition occurs because we previously described this house, explained the grounds for finding it, which was reflected in our ideas about it.

It should be noted that the processes of recognition differ from each other degree of certainty. Recognition is the least definite in those cases where we have only a sense of familiarity with an object, but we cannot identify it with anything from past experience. For example, we see a person whose face seems familiar to us, but we cannot recall who he is and under what circumstances we could meet him. Such cases are characterized by uncertainty of recognition. In other cases, recognition, on the contrary, is characterized by complete certainty: we immediately recognize a person as a certain person. Therefore, these cases are characterized by full recognition.

It should be noted that there is much in common between definite and indefinite recognition. Both of these recognition options are developed gradually, and therefore they are often close to recalling, and therefore are a complex thought and volitional process.

Along with different types of correct recognition, there are also errors in recognition. For example, what is perceived for the first time sometimes seems familiar to us, already experienced once in exactly the same way. An interesting fact is that the impression of familiarity can remain even when we firmly know that we have never seen this item or were not in this situation.

In addition, you should pay attention to another, very interesting feature of recognition and reproduction. The processes of recognition and reproduction are not always carried out with equal success. Sometimes it happens that we can recognize an object, but we are unable to reproduce it when it is absent. There are cases of the opposite kind: we have some ideas, but we cannot say what they are connected with. For example, we are constantly “pursued” by some kind of melody, but we cannot say where it comes from. Most often, we have difficulty in reproducing something, and much less often such difficulties arise during recognition. As a rule, we are able to find out when it is impossible to reproduce. Thus, we can conclude:

recognition is easier than reproduction.

Forgetting is expressed in the inability to recover previously perceived information. The physiological basis of forgetting are certain types of cortical inhibition, which prevents the actualization of temporary neural connections. Most often this is the so-called extinctive inhibition, which develops in the absence of reinforcement.

Forgetting manifests itself in two main forms: a) impossibility to recall or learn; b) incorrect recollection or recognition. Between full reproduction and total forgetting, there are various degrees of reproduction and recognition. Some researchers call them "memory levels." It is customary to distinguish three such levels: 1) reproducing memory; 2) identification memory; 3) facilitating memory. For example, a student learned a poem. If after a while it can reproduce it without error - this is the first level of memory, the highest; if he cannot reproduce the memorized, but he will easily recognize (recognize) the poem in the book or by ear - this is the second level of memory; if a student is unable to remember or learn a poem by himself, but when he learns again, it will take less time for full reproduction than for the first time, this is the third level. Thus, the degree of manifestation may vary. The nature of the manifestation of forgetting may be different. Forgetting can be manifested in the schematization of the material, the discarding of individual, sometimes essential, parts of it, the reduction of new ideas to the usual old ideas.

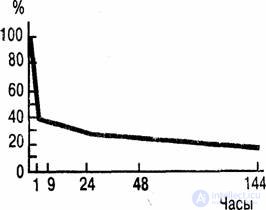

Attention should be paid to the fact that forgetting is uneven in time. The greatest loss of material occurs immediately after its perception, and further forgetting is slower. For example, Ebbingauz’s experiments, which we talked about in the first section of this chapter, showed that an hour after memorizing 13 meaningless syllables, forgetting reaches 56%;

however, it goes slower (Fig. 10.3). Moreover, the same pattern is typical for forgetting meaningful material. This is confirmed by an experiment conducted by the American psychologist M. Jones. The experiment was as follows: prior to the beginning of the lecture on psychology, Jones warned students that at the end they would receive leaflets with questions on the content of the lecture, to which written answers should be given. The lecture was read at a speed of 75 words per minute, clearly and accessible.

Fig. 10.3. The “forgetting curve” of Ebbinghaus

A written survey was conducted five times at different time intervals. The results were as follows: right after the lecture, the students correctly reproduced 65% of the basic ideas of the lecture, three or four days after the lecture — 45.3%, one week later — 34.6%, two weeks later — 30.6% and eight weeks later - 24.1%.

An outstanding lecturer invited to compare the data did almost the same thing: the students immediately after the lecture reproduced 71% of his basic thoughts, and then the forgotten material went on forgetting: first, faster, and then somewhat slower. It follows from this experience that if students do not work on fixing educational material in memory, in two months only 25% of it will remain, and the greatest loss (55%) will occur in the first three to four days after perception.

In order to slow down the process of forgetting, it is necessary to organize the repetition of the perceived material in a timely manner, without delaying this work for a long time. This is well confirmed by the research of M. N. Shardakova. He established that if the received material is not repeated on the day of receipt, then in a day 74% of the material is stored in memory, in three or four days - 66%, in a month - 58 % and in six months - 38%. When the material is repeated on the first day, 88% remain in the memory every day, 84% after three or four days, 70% after a month and 60% after 6 months. If we organize a periodic repetition of the material, then the amount of stored information will be quite large for a considerable time.

Thus, to reduce forgetting it is necessary:

1) understanding, understanding the information (mechanically learned, but not completely understood information is forgotten quickly and almost completely);

2) information repetition (the first repetition is necessary 40 minutes after memorization). It is necessary to repeat more often in the first days after memorizing, since on these days the losses from forgetting are maximum. For example: on the first day - 2-3 repetitions, on the second day - 1-2 repetitions, on the third-seventh day, one repetition, then one repetition with an interval of 7-10 days. Remember that 30 repetitions per month are more effective than 100 repetitions per day. Therefore, systematic, without overload study, memorizing in small portions during a semester with periodic repetitions in 10 days is much more effective than concentrated learning of a large amount of information in a short period of a session, causing mental and mental overload and almost complete forgetting of information a week after the session.

Considering various options for forgetting, one cannot help saying about cases when a person cannot remember something at the moment (for example, immediately after receiving information), but remembers or recognizes it after some time. This phenomenon is called reminiscence (a vague memory ). The essence of the reminiscence is that the reproduction of the material, which we could not immediately fully reproduce, after two or two after perception is replenished with facts and concepts that were absent at the first reproduction of the material. This phenomenon is often observed during the reproduction of a large amount of verbal material, which is due to nerve cell damage. Reminiscence is found more often in preschoolers and younger students. Much less often this phenomenon occurs in adults. According to

DI Krasilytsikova, when playing the material, reminiscence is noted in 74% of preschoolers, in 45.5% of junior schoolchildren and in 35.5% of fifth- and seventh-grade schoolchildren. This is due to the fact that children do not always immediately comprehend the material when it is perceived, and therefore transmit it incompletely. They need some period of time for its comprehension, as a result of which the reproduction becomes more complete. If the material is meaningful immediately, then the reminiscence does not occur. This explains the fact that the older the students, the less often this phenomenon is observed in their memory.

Other forms of forgetting are erroneous recall and erroneous recognition. It is well known that what we perceived over time loses its brightness and distinctness in memory, becomes pale and unclear. However, changes in previously perceived material may also be of a different nature, when forgetting is expressed not in a loss of clarity and clarity, but in a significant discrepancy between the recalled and the truly perceived. In this case, we remember not at all what was in reality, since in the process of forgetting there was a more or less deep restructuring of the perceived material, its substantial qualitative processing. For example, one such example of processing may be the erroneous reproduction of a sequence of events over time. So, clearly reproducing individual events, a person in the meantime cannot recall their correct sequence. The main reason for this phenomenon, as shown by studies of L. V. Zankov, is that in the process of forgetting, random connections weaken in time, and instead, essential, internal relations of things (logical connections, similarities of things, etc.) come to the fore. ), which do not always coincide with connections in time.

Currently known factors affecting the speed of the processes of forgetting. So, forgetting proceeds faster if the material is not sufficiently understood by man. In addition, forgetting happens faster if the material is not interesting to the person, and is not directly related to his practical needs. This explains the fact that adults remember better what is related to their profession, which is related to their vital interests, and schoolchildren remember well the material that fascinates them, and quickly forget what they are not interested in.

The speed of forgetting also depends on the volume of the material and the degree of difficulty of its assimilation: the greater the volume of the material or the harder it is for perception. the faster the forgetting happens. Another factor accelerating the process of forgetting is the negative impact of the activity following memorization. This phenomenon is called retroactive braking. Thus, in the experiment conducted by A. A. Smirnov, a group of schoolchildren were given a number of adjectives to learn, and immediately after that a second series of words. After memorizing the second series of words, they checked how many adjectives children remembered. In another group of students, there was a five-minute break between memorizing the first and second rows of words. It turned out that schoolchildren, who studied the series of words without a break, reproduced 25% less adjectives than children who had a short break. In another experience, after memorizing adjectives, children were given a number of numbers to memorize. In this case, the reproduction of a series of words fell by only 8%. In the third experience, after memorizing words, difficult mental work went on - solving complex arithmetic problems. Reproduction of words decreased by 16%.

Thus, retroactive inhibition is more pronounced if the activity follows without interruption or the follow-up activity is similar to the previous one, and also if the follow-up activity is more difficult than the previous activity. In the latter case, the physiological basis of retroactive inhibition is negative induction: difficult activity slowed down more easily. This pattern must be borne in mind when organizing academic work. It is especially important to observe breaks in classes, alternate academic subjects so that there are significant differences between them - subjects that are difficult to master, set earlier than light ones.

Another significant factor affecting the speed of forgetting is age. With age, the deterioration of many memory functions. It becomes more difficult to memorize material, and, on the contrary, the processes of forgetting are accelerated.

The main significant causes of forgetting, beyond the average values, are various diseases of the nervous system, as well as severe mental and physical trauma (bruises associated with loss of consciousness, emotional trauma). In these cases, sometimes a phenomenon called retrograde amnesia occurs . It is characterized by the fact that forgetting covers the period preceding the event that caused the amnesia. Over time, this period may decrease, and even more so, forgotten events can be fully recovered in memory.

Forgetting also comes faster with mental or physical fatigue. The cause of forgetting may be the action of extraneous stimuli that prevent us from focusing on the necessary material, for example, annoying sounds or objects in our field of vision.

Memory, like any other cognitive mental process, has certain characteristics. The main characteristics of the memory are: volume, speed of capturing, accuracy of reproduction.

1. Memory size is the most important integral characteristic of memory, which characterizes the possibilities of storing and saving information. Объем памяти — количество информации, которое человек способен запомнить за определенное время. Объем кратковременной памяти человека в среднем составляет 7±2 блока информации. Объем блока может быть различным, например, человек может запомнить и повторить 5-9 цифр, 6-7 бессмысленных слогов, 5-9 слов.

2. Скорость запоминания – время, в течение которого человек способен запомнить определенный объем информации.

3. Другая характеристика памяти — точность воспроизведения . Эта характеристика отражает способность человека точно сохранять, а самое главное, точно воспроизводить запечатленную в памяти информацию. Как правило, встречаясь с необходимостью решить какую-либо задачу или проблему, человек обращается к информации, которая хранится в памяти.

Процессы памяти у разных людей протекают неодинаково. В настоящее время принято выделять две основные группы индивидуальных различий в памяти: в первую группу входят различия в продуктивности заучивания, во вторую — различия так называемых типов памяти.

Различия в продуктивности заучивания выражаются в скорости, прочности и точности запоминания, а также в готовности к воспроизведению материала. Общеизвестно, что одни люди запоминают быстро, другие медленно, одни помнят долго, другие скоро забывают, одни воспроизводят точно, другие допускают много ошибок, одни могут запомнить большой объем информации, другие запоминают всего несколько строк.

Так, для людей с сильной памятью характерно быстрое запоминание и длительное сохранение информации. Известны люди с исключительной силой памяти.

Например, А. С. Пушкин мог прочесть наизусть длинное стихотворение, написанное другим автором, после двукратного его прочтения. Другим примером является В. А. Моцарт, который запоминал сложнейшие музыкальные произведения после одного прослушивания.

Domestic science known examples of phenomenal memory. Thus, A.L. Luria discovered an outstanding memory in a certain Sh., Who memorized various materials with equal speed, including senseless, and, moreover, in an extremely large volume. Sh. Could quickly memorize and accurately reproduce complex mathematical formulas, devoid of meaning, meaningless words, geometric figures. His memory was also remarkable for its marvelous durability: after 20 years he accurately recalled the content of the experimental material, the place of the experiment in which he participated, as well as what the experimenter was wearing, and other minute details of the situation and his actions.

Is there a connection between how quickly a person remembers and how long he remembers? Experimental studies have shown that there is no strict pattern. The positive relationship between strength and speed of memorization is more common, that is, the one who quickly learns remembers longer, but at the same time there is an inverse relationship. There is also no definite relationship between speed and accuracy of memorization.

Another group of individual differences concerns the types of memory. The type of memory determines how a person memorizes the material - visually, by ear or using movement. Some people, in order to remember, need a visual perception of what they remember. These are people of the so-called visual memory type. Others need hearing images to memorize. This category of people has an auditory type of memory. In addition, there are people who, in order to memorize, need movements and especially speech movements. These are people who possess motor type of memory (in particular, speech motor).

However, pure memory types are not as common. As a rule, most people have mixed types. So, the most commonly encountered are mixed types of memory - auditory-motor, visual-motor, visual-auditory. A mixed type of memory increases the likelihood of fast and long-term learning. In addition, participation in the memory processes of several analyzers leads to greater mobility in the use of educated systems of neural connections: for example, a person did not remember something by ear - he remembers visually. Therefore, it is advisable that a person memorizes izhrormatsnyu in different ways:

by listening, reading, viewing illustrations, making sketches, observing, etc.

The type of memory depends not only on the natural features of the nervous system, but also on education. The teacher, activating in the lesson the activities of various analyzers of pupils, thereby brings up a mixed type of memory in children. In adults, the type of memory may depend on the nature of their professional activities.

It is necessary to pay attention to the fact that the types of memory should be distinguished from the types of memory. The types of memory are determined by what we memorize. And since any person remembers everything: both movements, and images, and feelings, and thoughts, then different types of memory are inherent in all people and do not constitute their individual characteristics. At the same time, the type of memory characterizes how we memorize: visually, by ear or by motor. Therefore, the type of memory is an individual feature of the person. All people have all kinds of memory, but each person has a specific type of memory.

Belonging to one type or another is largely determined by the practice of memorization, that is, what exactly a person has to memorize and how he learns to memorize. According to Poem'1, a certain type of memory can be developed with the help of appropriate exercises.

In general, the initial manifestation of memory can be considered conditioned reflexes, observed already in the first months of a child's life, for example, the cessation of crying when a mother enters the room . A more distinct manifestation of memory is found when the child begins to recognize objects. For the first time it is observed at the end of the first half of life, and at first recognition is limited to a narrow circle of objects: the child recognizes the mother, other people who constantly surround him, things that he often deals with. And all this is recognized if there is no long break in the perception of the subject. If the time interval between recognition and perception of an object (the so-called “hidden period”) was sufficiently large, then the child may not recognize the object being presented to him. Usually this hidden period should not exceed several days, otherwise the child will not be able to learn something or someone.

Gradually, the range of items that the child learns increases. The hidden period is also extended. By the end of the second year of life, the child can find out what he has seen several weeks before. By the end of the third year - what was perceived a few months ago, and by the end of the fourth - what was about a year ago.

First of all, the child manifests recognition, the reproduction is found much later. The first signs of reproduction are observed only in the second year of life. It is the short duration of the hidden period that explains the fact that our first memories of childhood belong to the period of four to five years of age.

Initially, the memory is involuntary. In the pre-preschool and preschool years, children usually do not set themselves the task of remembering something. The development of arbitrary memory in preschool age occurs in games and in the process of education. Moreover, the manifestation of memorization is associated with the interests of the child. Children remember better what they are interested in. It should also be emphasized that at preschool age, children begin to memorize meaningfully, that is, they understand what they remember. At the same time, children mostly rely on clearly perceived connections of objects, phenomena, and not on abstract-logical relations between concepts.

The rapid development of memory characteristics occurs in school years. This is due to the learning process. The process of mastering new knowledge predetermines the development of primarily arbitrary memory. Unlike a preschooler, a schoolboy is forced to memorize and

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization, preservation, reproduction, recognition

Часть 2 10.3.1 Memory Specifications - 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization, preservation,

Часть 3 Sample Questions and Answers - 10. Mental processes Memory, memorization,

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology