Lecture

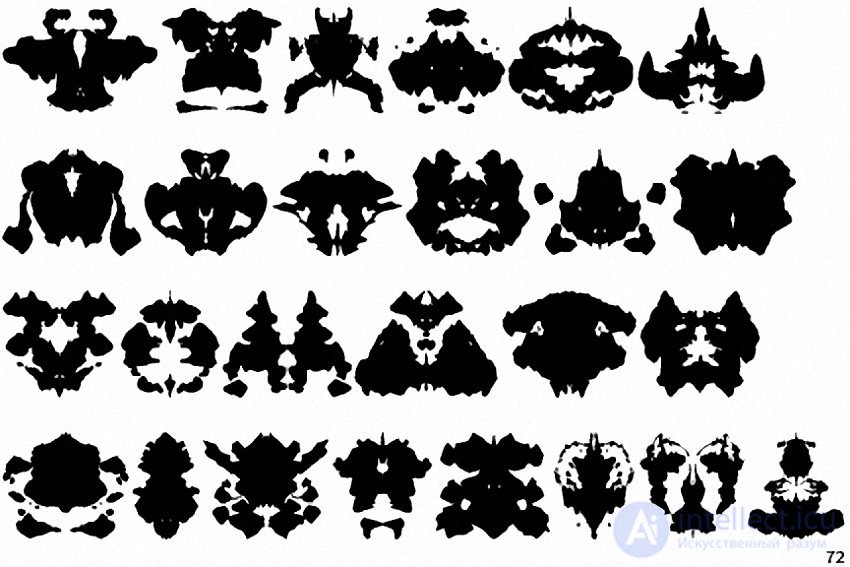

The Rorschach Test is a psychodiagnostic test for personality research, published in 1921 by the Swiss psychiatrist and psychologist Hermann Rorschach (it. Hermann Rorschach ). Also known as the “Rorschach stains” .

This is one of the tests used to study the psyche and its disorders. The subject is invited to give an interpretation of ten ink blots symmetric about the vertical axis. Each such figure serves as a stimulus for free association — the subject must name any word, image or idea he has. The test is based on the assumption that what an individual “sees” in a blob is determined by the characteristics of his own personality.

The test was developed by the Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922). Rorschach discovered that those subjects who see the correct symmetrical figure in a shapeless ink blot usually understand the real situation well, are capable of self-criticism and self-control. So the specificity of perception indicates the personality characteristics of the individual.

Studying composure, understood mainly as domination over emotions, Rorschach used ink blots of different colors (red, pastel shades) and different saturations of gray and black to introduce factors that have an emotional impact. The interaction of intellectual control and the emerging emotion determines what the subject sees in the blob. Rorschach discovered that individuals whose different emotional states were known from clinical observations actually respond differently to colors and shades.

The most original and important discovery of Rorschach, related to psychodynamics, is the Bewegung , or the answer, in which movement is used. Some subjects saw moving human figures in ink blots. Rorschach discovered that among healthy individuals it is most often characteristic of those who have a rich imagination, and among people with mental disabilities, for those who are prone to unrealistic fantasies. Comparing the content of the associations of fantasies with what was already known about the changes in the personality and the motivational sphere of the individual, Rorschach concluded that these associations are equivalent to the content of dreams. Thus, it turned out that ink blots are capable of uncovering deeply hidden desires or fears underlying long-lasting insoluble personal conflicts.

Significant information about the needs of the individual, about what makes a person happy or sad, what excites him, and what he is forced to suppress and translate into the form of subconscious fantasies, can be extracted from the content or “plot” of associations caused by ink stains.

After the death of Rorschach, his work was continued by many clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. The test has been further developed both in theory and in practice. The validity, adequacy and effectiveness of the Rorschach test has not yet been definitively established. Nevertheless, he helps a psychologist and a psychiatrist to obtain important data for the diagnosis of the person and her disorders, which can be clinically verified.

Stimulus material for the test consists of 10 standard tables with black and white and color symmetrical amorphous images.

Conducting research suggests the subject to look at a paper sheet with an ink spot of irregular shape and asks to describe what is shown in this “drawing”. Psychodiagnostics of personality is carried out according to a special method of interpretation.

Each answer is formalized with the help of a specially developed system of symbols in the following five countable categories:

The content of the answers is indicated by the following symbols:

More rare types of content are indicated by whole words: Smoke, Mask, Emblem, etc.

An example of the format for recording responses during a test:

The test causes controversy [1] ; in 1999, a moratorium was requested on the use of the test for clinical and judicial purposes [2] . A number of skeptics are classified as pseudoscientific methods. [3] [4]

The Rorschach method consists in the interpretation by the subject of random forms, i.e., figures formed at random. It is very simple to get such a random picture: several large ink blots are poured onto a piece of paper, then the paper is folded up, and the spots are smeared between the halves of the sheet. However, not every picture obtained in this way is worthy of use; this will largely depend on meeting certain conditions. The resulting forms should be relatively simple. Further, the distribution of spots throughout the table should correspond to certain laws of spatial harmony (rhythm): if it is absent, then it will be difficult to find good images on the table, therefore, many test subjects will not be able to interpret it, and their failure will be explained by the fact that nothing but “just a blob”.

If we take into account that each table from the test suite must not only have these common qualities, but also meet specific requirements, and that each table individually, like the entire series, must be repeatedly tested in practice before it turns out to be quite suitable. the test apparatus, it becomes clear that the creation of ten successful tables is not such a simple matter, as it may seem at first glance.

If we take into account that each table from the test suite must not only have these common qualities, but also meet specific requirements, and that each table individually, like the entire series, must be repeatedly tested in practice before it turns out to be quite suitable. the test apparatus, it becomes clear that the creation of ten successful tables is not such a simple matter, as it may seem at first glance.

The spots obtained by the above method symmetrically (perhaps with minor deviations) are displayed on both halves of the table. Asymmetrical images often do not cause much interest among the subjects. Symmetry gives the tables a certain amount of the spatial rhythm they need, although it often leads to subjects having stereotyped answers. On the other hand, due to symmetry, equal conditions are created for left-handers and right-handers; in addition, with its help, it becomes easier for some of the notorious and blocked people to find visual images. Symmetry also allows you to fully see the scene depicted on the table.

Presentation in the control experiment of new test tables, on which the subject will be able to see asymmetric and non-rhythmic images, will provide data based on new factors, but the study of individual susceptibility to spatial rhythm is in itself a topic worthy of special study.

A certain sequence of presented tables within one series is based on the obtained empirical data.

The test subject is presented one after another with test tables with the same question: “What do you think it could be?” He can rotate and rotate the table as he wants. It is allowed to move the table away from oneself; one cannot only consider it from afar; the largest distance between the subject and the table will be determined by the distance of the outstretched arm. Care must be taken to ensure that subjects do not see the table from afar, as this will distort the results obtained in the experiment. For example, Table I at a distance of several meters is often perceived as the “head of a fox”, while almost nobody sees near it. But if it seemed to the subject at least for a moment from afar that this was the “fox head”, it would be very difficult for him to get rid of the impression that there is something on the table other than this head.

It is necessary to insist (avoiding, of course, any suggestive moments) so that at least one answer is given to each table. However, the main task of the experimenter is to record in the protocol all the answers of the subject. Preliminary results showed that the time spent by the subjects on each answer does not affect the content of these answers, which means that this indicator can be neglected. The main thing is that the experiment was conducted in the most relaxed and relaxed atmosphere. Excessively disturbing patients may occasionally ad oculus 1 show how these pictures were obtained. But usually even the anxious and depressed mentally ill do not resist the experiment.

Almost all subjects view this experiment as revealing their ability to fantasize. Moreover, such a view is so widespread that it could be regarded as one of the preliminary conditions of our experiment. However, the interpretation of random forms is not directly related to fantasy, so it is not necessary to consider the widespread opinion as a valid condition for conducting an experiment. It is only true that people gifted with fantasy react differently than they are deprived of it. But on whether the experimenter will offer the subjects to give free rein to their imagination, the results of the experiment are unlikely to change. And from the subject who has a fantasy (which he easily demonstrates in the experiment), and from the one who does not have it (he even has to look for excuses for her absence) - valuable information will be obtained from both in the experiment. So the wealth or poverty of fantasy does not affect the achievement of reliable results.

The interpretation of random images is much more determined by the processes of perception and thinking.

“The perception of objects becomes possible as a result of the fact that sensations, or a group of sensations, ekforiruyut 2 (awaken) in us the images of memories associated with any previously formed group of sensations. As a result, a certain complex of previous sensations emerges in the mind, the elements of which, through more or less frequent experiences, have acquired a particularly strong interrelation and are clearly distinguished from other groups of sensations. Thus, three mental processes are immediately included in the process of perception: sensation, memory, and comparison. The identification (identification) of one of the complexes of sensations in all its interrelations is called understanding ”(Bleuler 3. Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie, Verlag Springer, Berlin, 1916, S. 9).

Since perception is an associative equating of the existing n engrams of the individual 4 (images of memory) to the newly created complex of sensations, the interpretation of random forms can be represented as a special kind of perception in which mental efforts aimed at comparing the complex of newly arising sensations with engrams, so large that, intrapsychically, they will be perceived as efforts expended on comparison. This intrapsychic perception of the incomplete equating of the complex of momentary sensations to the existing engrams gives the perception a character of interpretive activity.

Not all the answers of our subjects are interpretations in a similar sense. Most patients with organic lesions (senile dementia [senile dementia], progressive paralysis) and epilepsy, many people with schizophrenia and the majority of maniacs, almost all demented and a huge number of people who have a completely normal mind, do not even realize that from their side such mental activity takes place, which consists in comparing images. Instead of interpreting random images, they really see them. These subjects may even marvel at what other people see on the tables is not the same as them. This is easy to understand, since in the case of these subjects there can be no interpretation of any kind, because they perceive the real object here. They are just as little aware of the efforts they are making to associative comparison, as is the case when, for example, a normal person instantly recognizes a person he is familiar with or, without thinking, determines that there is a tree in front of him. It is probably worth admitting that there is a certain threshold, passing which perception, unconscious mental activity spent on the comparison, turns into an interpretation, into an understanding that we are spending efforts on this comparison. In weak-minded patients (including those suffering from senile dementia) and manic patients, this threshold is very high.

Where this threshold is very low, we will see the opposite: even the simplest, most everyday perception will be perceived intrapsychically as a tremendous effort expended on comparison. This is found in pedantic people who, in the process of perception, try to achieve the greatest fit between the complex of sensations received at the moment and the existing engrams. Even more clearly, this is found in some depressed patients, for whom the mental effort spent on comparison becomes so burdensome that they cannot come to anything at all, and everything that they perceive is seen to be “changed”, “alien”. In our experiment, pedants and depressed patients try to find on the test tables presented to them such details that appear with the greatest realism and clarity, although in this case similar test subjects often say: “I absolutely know that I just interpret what I see but in reality there is something else. ”

Normal subjects will most often spontaneously claim that they "interpret" the images that they see on the tables.

And those of the subjects who are distinguished by congenital or acquired intellectual inferiority, on the contrary, will be inclined to “recognize” familiar images. This fact indicates that the differences between interpretation and perception are associated with an associative (intellectual) aspect. The fact that the answers of people who are in a cheerful mood are more likely to have the character of true perception, and in patients who are in a depressed state - the nature of interpretation, also suggests that the differences found here are not determined exclusively by associative processes, Between perception and interpretation, affective factors come into play.

Thus, it can be concluded that the differences between perception and interpretation are, by their nature, individual and quantitative, and not at all principled and universal. It follows from this that interpretation can be only a special case of the process of perception. Therefore, there is no doubt that our experiment on the interpretation of forms has the right to be called a perception test.

On the meaning of fantasy for the interpretation of images, see here.

Note.

1 Ad oculus (лат.) — ясно, перед глазами.

2 Экфорировать — от греч. ekphorie, обозначающего мнестнческий процесс, воспоминание (Прим. перев.).

3 Ойген Блейлер (1857—1940) — профессор психиатрии Цюрихского университета (1898—1927) и директор знаменитой клиники «Бургхельцли», которой он стал руководить после своего учителя Августа Фореля. Вместе с заведующим одним из отделений клиники К. Г. Юнгом Блейлер был первым представителем академической науки, ставшим приверженцем и защитником фрейдовского психоанализа. Вместе с Фрейдом Блейлер издавал первое психоаналитическое периодическое издание — Jahrbuch fiir psychoanalytische und psychologische Forschungen (Ежегодник психоаналитических и психопатологических исследований) .

4 Engramm (Greek) - an inscription, in psychology, an engram means traces in the memory of lingering impressions (“dormant” images of memory).

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology