Lecture

The first inventor, mechanical computing machines, became the brilliant Frenchman Blaise Pascal. The son of a tax collector, Pascal decided to build a computing device, watching the endless tiresome calculations of his father. In 1642, when Pascal was only 19 years old, he began working on the creation of a summing machine. Pascal died at the age of 39, but, despite such a short life, he went down in history as an outstanding mathematician, physicist, writer, and philosopher. In his honor, named one of the most common modern programming languages.

Pascal's summing machine, "Pascalina", was a mechanical device - a box with numerous gears. In just over a decade, he built more than 50 different variants of the car. When working on “pascaline”, the added numbers were entered by means of the corresponding rotation of the dials. Each wheel with divisions from 0 to 9 applied to it corresponded to one decimal digit of the number - units, tens, hundreds, etc. Excess over 9 wheel "transferred", making a full turn and pushing the adjacent "older" wheel 1 forward. Other operations were performed using a rather inconvenient procedure of repeated additions.

|

1642 Pascal's summing machine produced arithmetic operations; Pascal's Summing machine rotated the connected wheels with digital divisions. |

Although the car caused a general delight, it did not bring Pascal wealth. Nevertheless, the principle of bound wheels invented by him formed the basis on which the axis of most computing devices was built over the next three centuries.

The main drawback of the “pascalines” was the inconvenience of performing all operations on it, except simple addition. The first machine, which allowed for easy subtraction, multiplication, and division, was invented later in the same seventeenth century. in Germany. The merit of this invention belongs to a man of genius, whose creative imagination seemed inexhaustible. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was born in 1646 in Leipzig. He belonged to a genus known for his scholars and politicians. His father, a professor of ethics, died when the child was only 6 years old, but by this time Leibniz had already mastered the thirst for knowledge. He spent days on end in his father’s library, reading books and studying history, Latin and Greek languages and other subjects.

Enrolling at the University of Leipzig at the age of 15, he, in his erudition, was probably not inferior to many professors. And yet now a whole new world has opened up before him. At university, he first became acquainted with the works of Kepler, Galileo, and other scientists who were rapidly expanding the boundaries of scientific knowledge. The pace of scientific progress struck the young Leibniz’s imagination, and he decided to include mathematics in his curriculum.

At the age of 20, Leibniz was offered a professorship at the University of Nuremberg. He rejected this proposal, preferring the life of a scientist to a diplomatic career. However, while he was traveling in a carriage from one European capital to another, his restless mind was tormented by all sorts of questions from various fields of science and philosophy, from ethics to hydraulics and astronomy. In 1672, while in Paris, Leibniz met the Dutch mathematician and astronomer Christian O. Huygens. Seeing how many calculations an astronomer has to do, Leibniz decided to invent a mechanical device that would facilitate the calculations. “Because it’s unworthy of such wonderful people,” Leibniz wrote, “like slaves, you lose time on computational work that you could entrust to anyone when using the machine.”

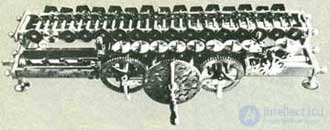

In 1673 he made a mechanical calculator. Addition produced an axis on it in essentially the same way as on “pascaline”, however Leibnitz included in the design a moving part (the prototype of the moving carriage of future desktop calculators) and a handle with which it was possible to turn a stepped wheel or - in subsequent versions of the machine - cylinders located inside the unit. This moving element mechanism accelerated the repetitive addition operations needed to multiply or divide numbers. The repetition itself was also automatic.

|

1673 Calculator Leibniz accelerated the multiplication and division operations. |

Leibniz showed his car at the French Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society of London. One copy of the car Leibniz came to Peter the Great, who gave it to the Chinese emperor, wanting to hit the European technical achievements. But Leibniz was famous first of all not for this machine, but for the creation of differential and integral calculus (which Isaac Newton developed independently in England). He also laid the foundations of the binary number system, which later found application in automatic computing devices.

Comments

To leave a comment

History of computer technology and IT technology

Terms: History of computer technology and IT technology