Lecture

General characteristics of the learning process

Analysis of instinctive behavior leads to the conclusion that all the wealth and variety of high-grade mental reflection are associated with learning, the accumulation of individual experience. Therefore, this category of behavior will be constantly in the center of our attention and we will more than once turn to different aspects of it, learn about different forms of learning. Here we consider only some general provisions.

When studying the processes of learning, it is necessary to proceed from the fact that the formation of behavior is a process of concrete embodiment in the life of an individual of the experience of a species accumulated and fixed in the process of evolution. It is this, as already noted, that determines the interweaving of innate and individually acquired components of behavior. Species experience is transmitted from generation to generation in a genetically fixed form in the form of innate, instinctive components of behavior, therefore, the behavior “encoded” in this way is always type-specific.

But this does not mean that the reverse is also true, that is, that each type-specific form of behavior is inherently innate, instinctive in its origin. There are such forms of learning, which outwardly resemble instinctive behavior, but nevertheless represent nothing more than the result of the accumulation of individual experience, albeit in hard types. These are primarily the forms of the so-called obligate learning, which, according to G. Tembrock, denotes the individual experience necessary for the survival of all members of this species, regardless of the individual living conditions of the individual. Related forms of learning will be considered when discussing the ontogeny of behavior.

In contrast to obligate facultative learning, according to the Timbre, includes all forms of purely individual adaptation to the peculiarities of the specific conditions in which this individual lives. It is clear that these conditions can not be the same for all representatives of this species. Serving, thus, the maximum specification of the species behavior in the particular conditions of the habitat of the species, optional learning is the most flexible, labile component of the behavior of animals. A number of important aspects of optional learning will also be discussed in more detail in connection with the ontogeny of behavior (part II, ch. 3). But we should immediately stipulate that the lability of facultative learning varies in different forms of its manifestation. The concretization of species experience by interweaving the elements of individual experience into the instinctive behavior is performed at all, even the rigid, stages of the behavioral act, although, as we already know, to different degrees. Thus, the English ethologist Raheind points to a modification of instinctive behavior by learning processes by changing the combination of stimuli causing a certain instinctive act, isolating (or enhancing) certain directional key stimuli, etc.

At the same time, it is essential that modifications can take place both in the sensory and effector spheres, although most often they cover both spheres simultaneously. In the effector sphere, the incorporation of elements of learning into instinctive actions occurs most often in the form of recombination of innate motor elements, but new motor coordination may also arise. Especially often it occurs at earlier stages of ontogenesis. An example of the emergence of such new motor coordination is the imitative singing of birds. In higher animals, as we shall see, the newly learned movements of effectors, especially of the extremities, play a particularly large role in cognitive activity and in intellectual behavior.

As for the "embedding" of individually variable components in instinctive actions in the sensory sphere, this significantly expands the possibilities of orientation of the animal thanks to the mastery of new signals. At the same time, unlike the key stimuli that are initially biologically significant for an animal, the stimuli that guide the animal in learning are initially indifferent (or, more precisely, almost so). Only as the animal memorizes them during the accumulation of individual experience, do they acquire a signal value for it. Thus, the learning process is characterized by selective isolation of some “biologically neutral” properties of environmental components, with the result that these properties acquire biological significance.

Now we already know that this process cannot be reduced simply to the formation of conditioned reflexes. The situation is much more complicated, primarily due to the truly active selective attitude of the organism to the elements of the environment.

The basis for this are the diverse dynamic processes in the central nervous system, mainly in its higher divisions, due to which afferent synthesis of stimuli due to external and internal factors is carried out. These irritations are compared with previously perceived information stored in memory. As a result, a readiness is formed for the implementation of various response actions, which is manifested in the initiative, selective nature of the animal's behavior in relation to environmental components.

The following analysis of the results of the animal's actions (on the basis of feedback) serves as the basis for a new afferent synthesis. As a result, in addition to congenital, specific behavioral programs in the central nervous system, new, acquired, individual programs are constantly being formed, on which learning processes are based. The physiological mechanisms of this continuous programming of behavior were analyzed in detail by P. K. Anokhin and were reflected in his concept of “acceptor of action results”.

It is very important here that the animal is not doomed to passive "blind obedience" to environmental influences, but itself builds its relations with environmental components and at the same time has a certain "freedom of action", more precisely, freedom of search and choice.

Thus, the formation of effective programs of forthcoming actions is the result of complex processes of comparing and evaluating internal and external stimuli, specific and individual experience, recording the parameters of actions taken and checking their results. This is the basis of learning.

As we already know, the implementation of species experience in individual behavior is most in need of learning processes in the initial stages of search behavior. After all, it is at these first stages of each behavioral act that the animal’s behavior is most uncertain, it is here that it requires maximum individual orientation among the heterogeneous and changeable components of the environment, and fast selection of the most effective methods of action is especially important in order to reach the final phase of the behavioral act faster and in the best way . At the same time, an animal can rely only on its own experience, because the reactions to single, random signs of each specific situation in which any representative of the species may find itself could not, of course, be programmed in the process of evolution.

But since without the inclusion of acquired elements in instinctive behavior, the latter is impracticable, this inclusion itself is also hereditarily fixed, as are the instinctive components of behavior. In other words, the range of learning is also strictly species-specific. A representative of any kind cannot learn "anything", but only that which helps to advance towards the final phases of type-typical behavioral acts. There are, therefore, type-specific, genetically fixed “limits” of learning ability.

The framework of disposition to learning not only corresponds to the real conditions of life, but in higher animals they are sometimes even wider than those conditions require. Therefore, higher animals have significant reserves of behavioral lability, the potential for individual adaptation to extreme situations. In lower animals, these possibilities are sharply narrowed, as in general, the ability to learn does not reach as high a level as in higher animals. Therefore, the breadth of learning ability ranges, the presence of these reserve capabilities are indicators of the height of the mental level of animals. The wider these ranges and the greater the potential for learning beyond the usual norm, the accumulation and application of individual experience in unusual conditions, the more and better the instinctive behavior can be corrected, the more labile the search phase will be, the more plastic the whole behavior of the animal and the higher is his general mental level.

This is a process of dialectic interaction, in which the cause and effect are constantly changing places: the complication in the process of evolution of instinctive behavior requires an expansion of the range of the ability to learn; the intensified inclusion of the elements of learning in instinctive behavior makes the latter more plastic, that is, it leads to a qualitative enrichment of this behavior and raises it to a higher level. As a result, the behavior evolves as a whole.

These evolutionary transformations encompass both the content of innate behavioral programs and the possibility of enriching them with individual experience and learning. At the lower stages of the evolution of the animal world, these possibilities are limited to habituation, training, and summation processes in the sensory sphere (see part III). The temporal connections that appear in the lower invertebrates are still very unstable, then they become more and more strong, reaching full development in various kinds of skills. With habituation, reactions to a certain repetitive irritation that is not accompanied by a biologically significant effect on the animal gradually disappear. The opposite phenomenon can be considered training, in which instinctive action is improved by the accumulation of individual experience.

The difference in behavior between lower and higher animals is not that the more primitive forms of behavior are replaced by more complex ones, but that the second ones are added to the first ones, significantly enriching and changing them, as a result of which the elementary forms of behavior acquire considerable complexity and become more variable So addictive, with the elementary form of which we are still acquainted with the example of the behavior of the simplest, appears in mammals in very complex manifestations. For example, as shown by experiments conducted by Hindn in collaboration with Skaurs, in mice, the reactions of these animals to repetitive but unsupported acoustic stimuli weaken with unequal speed. But these differences in addiction are caused not only by differences in the intensity of stimuli (as is the case in lower animals), but above all by the variability of the addiction process itself.

The main qualitatively new component of learning, complementing and enriching the primary primitive forms of behavior, is the skill, which, however, at different evolutionary levels also manifests itself in significantly different forms.

Skill

Main features of skills

Skill is the central, most important form of optional learning. Sometimes the term “skill” is used to mean learning in general. However, as A. N. Leontyev emphasizes, it is impossible to call any connection that arises in individual experience as skills, because with such an expanded understanding the concept of skill becomes very vague, and thus unsuitable for rigorously scientific analysis. It has already been pointed out that the ability to develop skills is not peculiar to all animals, but is manifested only at a certain level of phylogenesis. As a result of the formation of the skill, inborn motor coordination (of normal behavior) is applied in the new signal situation or a new (acquired) motor coordination arises. In the latter case, new, genetically fixed movements appear, that is, the animal learns to do something in a new way. But in any case, the success of the movements performed and their reinforcement with a positive result is crucial. In this case, essentially, it does not matter whether learning is based on information obtained through its own active search for irritants, or in the course of communication with other animals, communications, which also include instances of imitation or training (by a human being - an animal, by an adult individual - a cub, etc.) P.).

Another important attribute of the skill, which is also associated with the need for reinforcement, is that it is formed as a result of the exercise and needs to be further maintained in training. When training skills are improved, in the absence of its extinct, destroyed.

Skills are intensively studied in animals with the help of various special methods: “labyrinth”, “problem box” (or cage), “workaround”, etc. With all these methods, the animal is placed in the conditions for selecting signals or methods of action when solving a specific task.

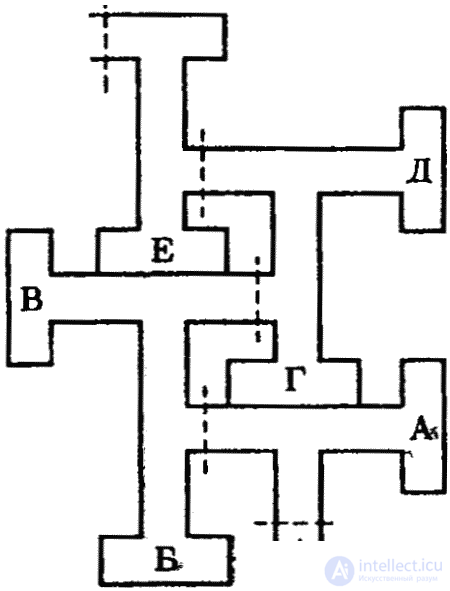

The “labyrinth” method already described above was introduced into the practice of experimental research in 1901 by the American psychologist V. S. Small. Currently, labyrinths of the most diverse designs are used (see Fig. 1), but the task that the experimental animal has to solve is always the same — to reach the reinforcement site (most often food), as quickly as possible and without dead ends. Most of the experiments were carried out with rats who easily cope with such tasks. There is practically no labyrinth in which the rat could not navigate. Especially intensively used labyrinths, as well as problem boxes and cells (also already described), behaviorists. The problem box was improved and equipped with automatic devices by the American psychologist B. F. Skinner. It also used rats as experimental animals.

In the labyrinth, the animal solves the problem as if “blindly”, since the reaction (running) is developed without direct contact with the stimulus (food, nest) causing it, and moreover, the animal at the beginning of the experiment still knows nothing about the presence of the target object, but only accidentally discovers it later as a result of indicative research activities. Memorizing this object and the path to it are the basis for the formation of a skill. If subsequently an animal repeatedly runs through this distance using the same shortest path learned, then this skill becomes stereotypical, automated. The plasticity of behavior in this case is small, and with a strongly pronounced stereotype of the learned movements, the latter sometimes approach the instinctive motor stereotypes. Stereotyping is generally characteristic of primitive skills in which rigid, automated motor responses are formed. Considerable plasticity is manifested in such skills only at the first stages of the formation of these skills. (With higher order skills that are notable for their great plasticity, we will meet later.)

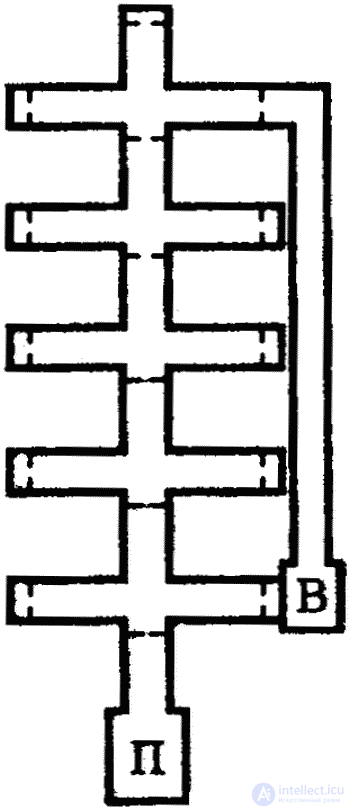

Skills development by the method of Skinner is called "operant" or "instrumental" conditioning. When solving such problems, the animal must show a motive initiative, independently “invent” a method of action and operation. Certain movements are not “imposed” on the animal by the experimenter, as is the case with the development of “classical” conditioned reflexes according to Pavlov's method. When training a rat in the Skinner "problem box", a temporary connection is formed after a series of random movements (clicks on the planochka), supported by the appearance of food in the feeder. In more complex installations, rats are even given the opportunity to choose between two modes of action, leading to different results. So, for example, it is possible for a rat to be given an opportunity “at its discretion” to regulate the temperature in the “problem” box, including that heating reflector, then the cooling fan according to its needs. Each time the lever is pressed, the reflector is alternately turned on and the fan is turned off or vice versa (Fig. 11).

With “classical”, Pavlovian conditioning, “respondent” behavior is observed, that is, the answer follows the stimulus, and as a result of the formation of a conditioned reflex communication, reinforcement (unconditioned stimulus) is associated with the stimulus. With operant conditioning, a movement (response) is first performed, followed by reinforcement without a conditioned stimulus. But as with the “classical” development of conditioned reflexes, an adequate response of the animal (in this case, motor reflex) is reinforced here by a useful result for the animal. При этом потребность в пище или создании оптимальных температурных условий побуждает крысу реагировать на рычаг выученным образом, точнее, ориентировать свое поведение в соответствии с восприятием рычага. Это восприятие действует как условное раздражение постольку, поскольку действие рычагом приводит к биологически значимому результату — пищевому или температурному подкреплению. Вне этой временной связи рычаг не имеет для крысы никакого значения.

Тот факт, что при павловском обусловливании действует сначала условный агент (условный раздражитель, например звук метронома или вспышка лампочки), а уже затем безусловный (например, вкусовое ощущение в результате пищевого подкрепления), не следует переоценивать, так как и условный рефлекс может быть выработан лишь при наличии внутренней готовности животного, т. е. соответствующей потребности. У вполне сытого животного невозможно выработать условный рефлекс на пищу.

Выше уже говорилось о роли первичной (инстинктивной) мотивации в поведении животных.

По существу, оперантное обусловливание по Скиннеру в сравнении с «классической» павловской постановкой эксперимента охватывает лишь упрощенный, укороченный поведенческий акт: вне внимания оставляется первая фаза — фаза ориентации животного во времени и пространстве. При выработке «классического» условного рефлекса животное должно сперва по внешним ориентирам научиться тому, когда, при каких сопутствующих внешних условиях следует произвести соответствующее движение. Вот эта первичная ориентация животного во времени по внешним сопутствующим признакам не учитывается при упомянутой постановке опытов по методу Скиннера. Равным образом не учитывается и пространственная ориентация, т. е. как животное находит рычаг, как научается пользоваться им, — словом, как ориентирует свои движения в пространстве. А ведь это является самым важным для подлинного психологического анализа поведения животного. Вместо такого анализа структуры деятельности при формировании двигательного навыка бихевиористами учитываются лишь временные параметры этого процесса (например, число нажатий за определенное время) без соответствующего качественного анализа.

В противоположность этому «классическая» павловская методика уже по самому существу своему принципиально верно моделирует естественные условия формирования поведения животного, так как направлена на анализ первичной ориентации животного по признакам компонентов среды, по которым животному необходимо ориентироваться в самом начале любого поведенческого акта. Преимущества такого подхода становятся ясными, если вспомнить, что говорилось выше о первом этапе поискового поведения.

Of course, as noted, we can no longer limit ourselves to “classical” conditioned reflexes when studying learning processes, in particular skills. And, of course, “problem boxes”, labyrinths and similar installations are absolutely necessary to study the formation of skills in different conditions, to identify the abilities of animals to solve problems of different degrees of complexity. It is only important, along with quantitative, to produce a qualitative analysis of the structure of the behavior of the animal in the course of solving the task set for it.

Training

Если при оперантном обусловливании животному предоставляется максимальная возможность проявить инициативу, самостоятельно выбрать способ действия в ходе решения задач, то при дрессировке, наоборот, навыки вырабатываются всецело под целенаправленным воздействием человека и в соответствии с его замыслом. Дрессировка осуществляется путем систематической тренировки животного, при которой подкрепляются требуемые двигательные реакции и их сочетания и упраздняются нежелательные движения. В результате дрессировки, как правило, вырабатываются прочные и четко скоординированные двигательные акты, достигающие подчас большой сложности. Выполняются они животным всегда в ответ на подаваемые человеком сигналы.

При цирковой дрессировке, рассчитанной на зрелищный эффект, раньше практиковался преимущественно болевой метод — наказание (иногда весьма жестокое) животного за каждое неправильное движение. В настоящее время его в основном сменил гуманный (и более эффективный) метод дрессировки, основанный на учете особенностей естественного поведения животного, его предварительном приручении, хорошем с ним обращении и пищевом подкреплении правильно выполняемых движений. Иногда применяется смешанный метод — поощрение правильных и наказание за неправильные движения. Дрессировка находит также широкое практическое применение во многих сферах хозяйственной и военной деятельности человека (служебное и охотничье собаководство).

В научных исследованиях широко пользуются разными формами дрессировки для изучения различных аспектов психической деятельности животных. Четкость условий, в которые ставится животное, и возможность точного учета сигнальных раздражителей (подаваемых экспериментатором сигналов) делают научную дрессировку незаменимой при изучении навыков животных.

Дрессировка является значительно более сложным процессом, чем простое обусловливание, и не сводится лишь к выработке цепей условных рефлексов. Специфическая трудность заключается в том, чтобы дать животному понять, что от него требуется, какие движения оно должно выполнить. Между тем эти движения хотя и входят в видотипичный репертуар поведения, являются зачастую непривычными или трудноосуществимыми в заданных дрессировщиком условиях. Советский зоопсихолог МА.Герд, детально разработавшая теорию дрессировки, делит поэтому процесс дрессировки на три стадии: наталкивания, отработки и упрочения.

На первой стадии решается задача — вызвать впервые ту систему движений, которая нужна человеку, «натолкнуть» животное на ее выполнение. Это достигается тремя путями: путем непосредственного наталкивания, косвенного наталкивания или сложного. В первом случае дрессировщик заставляет животное следовать или поворачиваться вслед за пищевым или иным привлекательным для животного объектом. Во втором случае провоцируются движения, непосредственно не направленные на приманку, но обусловливаемые общим возбуждением животного (так формируются преимущественно манипуляционные действия, выполняемые конечностями: обхватывание, перенос, удары или царапанье лапами и т. д.). Так, например, для создания циркового номера (раскатывание ковра лисицей) дрессировщик, стоя около свернутого ковра, поддразнивает ее куском мяса, но не дает схватить его. Возбужденное животное подскакивает, привстает, перебирает передними лапами и т. д. Все случайные прикосновения к ковру при этом закрепляются небольшими кусками пищи, в результате чего лисица все чаще будет обращаться к ковру, и наконец, появятся нужные дрессировщику движения лапой по ковру. В дальнейшем эти движения отрабатываются, направляются на середину рулона и т. д.

При сложном наталкивании, по Герд, дрессировщик вначале вырабатывает у животного определенный навык, а затем изменяет ситуацию, заставляя животное по-новому применять выработанное умение. Так, балансирование мячом на кончике носа вырабатывается у морских львов после того, как они научились сбрасывать его в руки дрессировщику. Убирая руки из поля зрения зверя, пряча их за спину, дрессировщик заставляет его несколько задерживать мяч на кончике носа, ибо подкрепление (рыба) будет получено животным лишь после того, как мяч окажется в руках человека. Путем обильного подкрепления постепенно увеличивается длительность удерживания мяча, и в конечном итоге получается знаменитый коронный цирковой номер.

Вторую стадию дрессировки, стадию отработки, Герд определяет как этап, на котором совершается отсечение многих лишних движений, вначале сопровождающих необходимые действия животного; далее — отшлифовка первичной, еще весьма несовершенной системы движения и, наконец, выработка удобной сигнализации, с помощью которой дрессировщик в дальнейшем управляет поведением животного. Усилия дрессировщика на этой стадии направлены на упразднение ориентировочных реакций, движений, обусловленных страхом, и иных помех, а также на упорядочивание последовательности, направленности и длительности вырабатываемых движений. Необходимо также заменить реакцию на пищу реакцией на подаваемый дрессировщиком сигнал. При всем этом вновь используются некоторые приемы наталкивания. Например, чтобы отшлифовать у медведя удерживание бутафорного «торта», используется «дробное» наталкивание: дрессировщик поднимает пищевую приманку на нужную высоту и относит ее чуть вбок, в результате чего коробка, которая раньше прижималась медведем к низу живота, поднимается им на уровень груди и немного в сторону. Это правильное положение фиксируется минимальным или средним подкреплением. Равным образом правильная осанка медведя фиксируется приманкой, удерживаемой над его головой, и т. д. С помощью наталкивающих воздействий; производится и выработка искусственной сигнализации.

Заключительная стадия процесса дрессировки, стадия упрочения, характеризуется усилиями дрессировщика, направленными на закрепление выработанного навыка и надежность его воспроизведения в ответ на подаваемые сигналы. Дробное наталкивание (приманивание) применяется уже крайне редко, а пищевое подкрепление осуществляется; уже не после нужного элемента, навыка, а преимущественно после целого комплекса выполненных движений. Вообще кормление производится реже, на более крупными порциями. Выработанные в результате навыки приобретают стереотипную форму при которой конец одного действия может послужить началу последующего.

Произведенный Герд анализ процесса дрессировки убедительно показывает исключительную сложность, гетерогенность в многоплановость поведения животных при выработке у них искусственный навыков. Но не менее сложная картина обнаруживается и для формировании навыков у животных и в естественных условиях. Об этом всегда следует помнить при ознакомлении с лабораторными экспериментами, где предельное искусственное упрощение и схематизация форм поведения животных являются залогом успеха научного исследования.

Познавательные процессы при формировании навыков

Еще в начале нашего века сложилось мнение, что образование навыков — как в отношении ориентации среди элементов среды, так в отношении формирования новых сочетаний движений — происходит путем «проб и ошибок». К этому выводу пришел в результате своих исследований ряд выдающихся ученых — Г. Спенсер, К. Ллойд-Морган, Г. Дженнингс, и, прежде всего Э. Торндайк. Согласно концепции «проб и ошибок», животное запоминает то, что случайно привело к успеху, все остальное постепенно отсеивается. Иными словами, в результате «проб и ошибок» совершается отбор и закрепление случайно произведенных удачных движений, что и приводит в конце концов путем многократных повторений к формированию двигательного навыка. Конечно, при этом отсутствует какое бы то ни было понимание связей и отношений между компонентами научения. Существенным здесь является представление, что «пробы и ошибки» совершаются беспорядочно.

Однако, как уже было доказано, образование навыков является значительно более сложным процессом и определяется активным отношением животного к воздействующим на него факторам среды. Еще в 20-е годы Э. Толмен, В. П. Протопопов и другие возражали против представления о хаотичности движений, производимых животными при решении задач, и показали, что эти движения формируются в процессе активной ориентировочной деятельности. Пои этом животное анализирует ситуацию и избирает то направление движений, которое соответствует положению «цели». В результате движения животного становятся все более адекватными ситуации, в которой дана задача. Таким образом, на место случайного возникновения движений ставится, как решающий фактор, активный двигательный анализ ситуации.

This view has been confirmed in a number of experimental studies. Thus, the American scientist I. F. Deshiell showed that test races into the dead ends of a labyrinth are not at all random, but, as a rule, are made towards the “goal”: after the first orientation in the maze, the animal creates a general system of direction of its movement; at the same time, the rat is much more likely to reach dead ends located towards the target than those located in the opposite direction (Fig. 12). Similar data were obtained by K. Spence and V. Shipley (Fig. 13).

The direction of action in the development of skills, resulting from the initial active orientation of the animal, prompted I. Krechevsky to put forward the thesis about the appearance in the animal of a kind of "hypotheses" that guide it in solving problems. This is especially revealed in those cases when an obviously unsolvable task is posed to an experimental animal, for example, when the labyrinth passages are closed and opened in an irregular sequence (Fig. 14). In this case, different groups of experimental animals appear different, but always stable types of behavior. According to Krechevsky, animals are trying to get out of difficulty by building a “hypothesis” and testing its suitability. In case of failure, the animal replaces it with another “hypothesis”. Therefore, the actions on a single “hypothesis” are repeated many times, until its unsuitability is revealed. Correspondingly, an animal behaves in the same way for some time, regardless of changing external conditions. Thus, in the above-mentioned labyrinth of Krechevsky, which rats, for example, were initially folded on all forks in the same direction. Making sure that this "hypothesis" does not lead to success, they began to constantly turn in the opposite direction.

In other cases, the rats began to regularly alternate turns to the left and right. Thus, a clear link is found between the previous attempt and the subsequent one, the animal, as it were, seeks to organize its behavior according to one “principle”. Krechevsky believed that this to a certain extent the abstract "principle" is systematic and due to the inner "tuning" of the animal.

The concept of Krechevsky is certainly not free from flaws, and the term “hypothesis” itself is extremely unfortunate in relation to the behavior of animals. However, the great merit of this scientist lies in the fact that he convincingly showed the entire complexity of the behavior of the rat in the maze (and other similar situations), especially in the initial period of solving the problem, when the research role of the animal plays a decisive role. No less valuable in this concept is that the emphasis is placed on the activity and initiative of the animal and emphasizes the role of internal factors (the mental attitude of the animal) in the process of solving problems.

The thesis of the "randomness" of attempts to solve problems and experiences using the "latent learning" is refuted. In such experiments, the rate of skill formation in animals is compared, which immediately before the start of the experiment is placed in a labyrinth or a “problem” box, with that in animals, which were given the opportunity to actively actively familiarize themselves with the installation and run around in it. In the latter case, motor skill is developed much faster.

In this regard, it is important to note that each rat that first entered the labyrinth behaves differently, especially at the initial orienting phase preceding the solution of the problem, when the jogs are completed without any reinforcement and only serve to accumulate experience. Even the modality of the leading reception varies during the initial examination of the labyrinth (some rats are guided mainly by visual, others by kinesthetic stimuli, etc.).

A rat, simply running through the maze, will know it even before solving a problem related to obtaining food reinforcement (or punishment) for correct (or incorrect) orientation. Of course, the individual characteristics of the research behavior of the animal also affect the course of the task itself. Significant individual differences in behavior in general are a characteristic feature of learning processes.

So, the active cognitive activity of the animal is the most important prerequisite for the successful formation of skill in solving problems. In essence, it is the cognitive component that determines the nature of the skill. According to Leontiev, the most important criterion of skill is the selection, when solving problems, of a special composition or side of an activity that meets the conditions in which an object is given that stimulates an animal's activity. Leontiev designated this component of the operation as an operation. The isolation of the operation in the motor activity of the animal indicates that we are really dealing with a true skill, and not with a different form of learning, therefore Leontyev considers only fixed operations as skills.

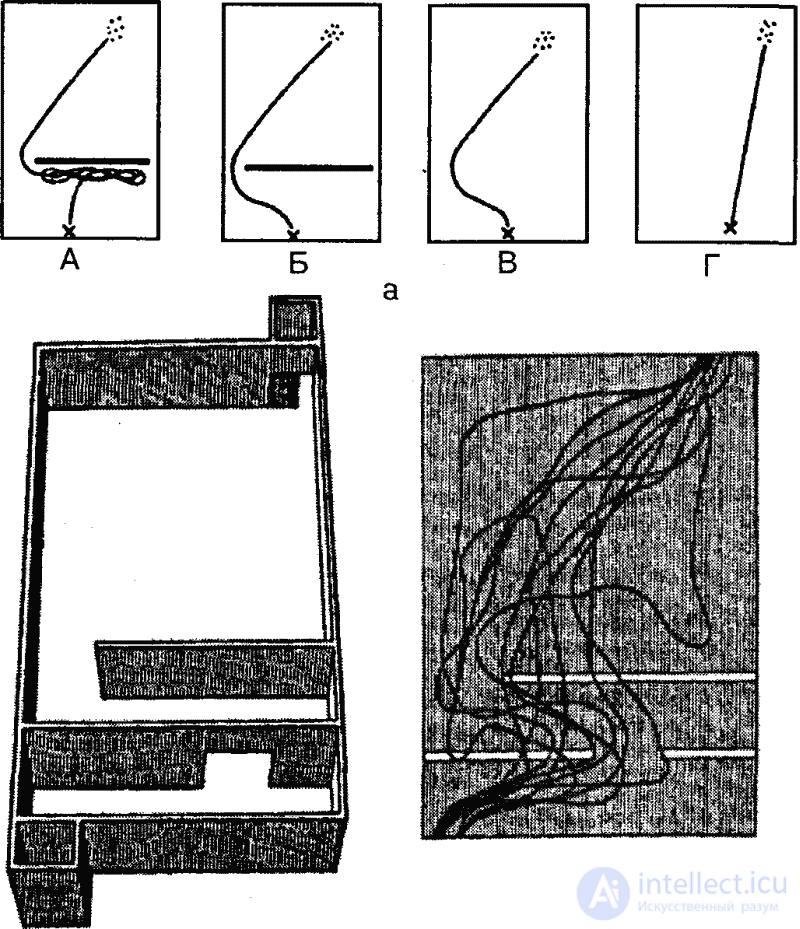

Allocation of the operation can be shown in a simple experiment conducted by A. V. Zaporozhets and I. G. Dimanshtein using the “workaround” method. A transverse gauze wall is placed in the aquarium so that a free passage remains at the side wall. At the beginning of the experiment, a test fish is placed in a smaller part of the aquarium, and a bait (pieces of meat) is placed in a larger fish, behind the partition. In order to get the bait, the experimental animal must bypass the barrier (partition), which he succeeds after a series of unsuccessful attempts to find the way to food straight. In search of a way to bait, an animal performs locomotor actions in which Leontyev isolates a dual content: 1) directional activity leading to a result and arising under the influence of the property of the object itself that stimulates activity (smells of meat), and 2) activity associated with the impact of an obstacle, t . e. with the conditions in which the subject is given to encourage the activity. It is this activity that will be the operation.

After the fish (in the described experiment - catfish) well learned the workaround, the barrier was removed, however the fish completely repeated the previous path, as if the obstacle were in place. Only gradually the way of the fish to the bait straightened out (Fig. 15, a). Similar experiments were performed with similar results in rats (Fig. 15, 6).

Consequently, the marked components of the activity here still come together; the impact, which determines the bypass movement, is still strongly associated with the impact of food, with its smell. The partition is not separated from the bait, the impact of the barrier is not yet perceived as a property of another thing - in short, the operation is not yet highlighted.

Regarding the experience described here with the catfish Leontyev writes that the activity of animals is already determined by the actual impact of certain things (food, obstacle), but the reflection of reality remains with them a reflection of the totality of its individual properties.

In the above example, the cognitive component, and accordingly the skill as a whole, is still at a very low level; the trajectory of the bypass path learned by animals turned out to be so firmly established that it was only gradually eliminated in the new environmental conditions (that is, after the partition was removed). This is a typical example of an automated skill. The more complex the skill, the greater its cognitive value and vice versa. In the skills of the highest rank, characteristic of higher vertebrates, the operation plays an extremely important cognitive role. However, in these animals, the consolidation of individual experience is often accomplished in the form of primitive skills like that described. The skill level depends in each specific case on the determining factors of the biology of the species and on the situation in which the animal encounters this or that more or less complex task.

Speaking about the structure and dynamics of the skill, it is important to emphasize that the concept of a barrier should not be understood only in the physical sense, as a barrier in the path of the animal. An obstacle is any obstacle to the achievement of an inducing object (“goal”) in solving a problem. Protopopov also emphasized this in his time, who was able to experimentally prove that any motor skills are formed in animals by overcoming the “obstacle”, that the content of the skills is determined precisely by the nature of the obstacle itself. The stimulus influences, according to Protopopov, the skill only dynamically, determining the speed and strength of its consolidation.

Thus, overcoming an obstacle constitutes the most essential element of the formation of a skill not only with it. development by the described method, but also with all other methods widely used in zoopsychological research. In particular, this refers to the methods of "labyrinth" and "problem box". It is in the ways of overcoming obstacles that the cognitive function of the skill manifests itself.

Studying the cognitive aspects of the formation of skills in animals, the Hungarian zoopsychologist L. Kardosh also showed that in the course of training in the maze an animal accumulates a significant amount of information. As a result, already at the beginning of the labyrinth, the animal “in memory ... sees beyond the walls covering its field of sensations; these walls become transparent. In memory, it “sees” the goal and the most important in terms of locomotion (movement) parts of the path, open and closed doors, ramifications, etc., “sees” exactly the same way and where it saw and in reality during the maze round ” . [36]

At the same time, Kardosh clearly showed the boundaries of the animal's cognitive abilities in the labyrinth, as well as in general when solving spatial and temporal problems. Here there are two possibilities: locomotor and manipulative cognition (the second occurs during the formation of instrumental skills). In the first case, the animal changes its spatial relation to the environment without the environment itself changing. If something changes in the environment of the animal as a result of a change in the behavior of the animal, then it is already a question of the manipulative activity of the animal. In studies carried out with I. Barkotsi, Kardosh showed that with great difficulty it is possible to teach a rat to choose different paths leading to the same point in the same maze and then move on in different ways, for example, directly or to the side (Fig. sixteen). This is an example of locomotor cognition. But, according to Kardos, it is impossible to train an animal (with the possible exception of apes) that depending on the choice of a particular path of movement, “something or the other happens”, i.e. changes in the environment will occur (in experiments replaced by another reinforcement - water). The man, as Kardosh writes, “would be surprised to find different subjects in the same place when he approached right and left, but he would learn after the first experience. It is here that development makes a leap ... A person can completely free himself from the directing influence of the spatial order, if temporal-causal connections require another. ” [37]

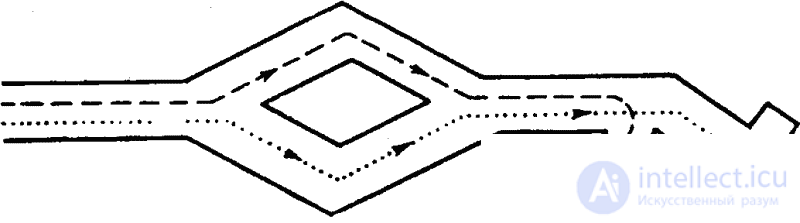

Learning and communication. Imitation

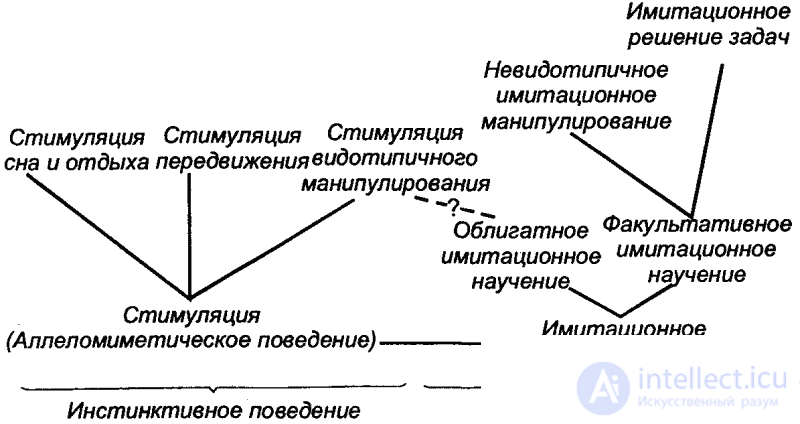

An important role in shaping the behavior of higher animals is played by imitation phenomena, which mainly, although not all, belong to the sphere of learning. We will not consider here the form of imitation, which relate to the instinctive behavior. This is a common reciprocal stimulation among animals — allelomimetic behavior (Fig. 17), in which the performance of species-like actions by some animals is a motivating factor for others. The latter, as a result, begin to perform the same actions (simultaneous rest, gathering food, etc.). Consequently, in this case mutual encouragement of type-typical activity takes place.

Learning by imitation (“imitational learning”) consists in the individual formation of new forms of behavior, but by only one direct perception of the actions of other animals. Thus, we are dealing here with learning through communication. Imitational learning, like all learning in general, can be divided into obligate and optional. With obligate imitational learning, the result of learning fits into the framework of the species stereotype. This is especially true for young animals, which by imitation learn to perform some vital actions of the usual behavioral "repertoire" of their own species. Thus, in young schooling fish, a defensive reaction to the appearance of a predator (flight) is formed as a result of imitation of the behavior of other fish with only one type of eating of members of the pack by a predator. L. A. Orbeli considered such imitative behavior as the “main guardian of the species”, because “a huge advantage is that the“ spectators ”who are present during the act of damaging a member of their herd or their community, produce reflex protective acts and thus can in the future avoid danger. " [38] Obligatory imitational learning is also an important element of the follow-up reaction (see Part II, Chap. 3) and the recognition of food objects by young mammals. Through obligatory imitational learning, young animals accumulate experience in nesting in birds (V.P. Promptov) and chimpanzees (J. van Lavik-Goodall), etc.

The facultative imitational learning in the simplest forms is represented in the imitation of invisible movements based on obligate (allelomimetic) stimulation. These include, for example, cases of monkeys imitating human actions, especially when they are kept at home. The actions they perform with household objects or tools, of course, are beyond the scope of species behavior. Since there is a learning of new techniques of manipulation, in this case we can talk about invisible imitation manipulation.

The highest manifestation of optional imitational learning should be clearly considered the solution of problems by imitation (or at least facilitating the solution). With this “imitational problem solving”, the “animal-viewer” develops a certain skill as a result of merely contemplating the actions of another individual, aimed at solving the corresponding task. The ability to do this is established in various mammals: apes and lower monkeys, dogs, cats, rats. In monkeys, imitative problem solving plays, obviously, a particularly large role. The Soviet animal behavior researcher A. D. Slonim, for example, believes that the formation of conditioned reflexes occurs in a monkey herd primarily on the basis of imitation. This is supported by field observations made by a number of researchers in recent years.

True, on the basis of imitational learning, “spectators” obviously cannot form instrumental skills. This is evidenced, in particular, by the experiments of the American researcher B. B. Beck, in which the "spectators" baboons observed the use of the instrument in solving the problem of a relative. The “spectators” were not capable of imitating the solution of such a complex task, but subsequently they were much more frequent and more intense than before the experiments, they manipulated this tool. This shows the activating role of allelomimetic behavior and invisible imitation manipulation in the development of complex skills in the context of communication.

The ratios of individual categories and forms of imitation in animals can be illustrated by a scheme (according to K. E. Fabry - see fig. 17).

This scheme is incomplete in that it does not reflect the phenomenon of imitation in the field of signaling and communication (for example, onomatopoeia in birds). However, there are no fundamental differences from the noted general laws and characteristics, and therefore this classification in its respective sections is fully applicable to this area. So, for example, to the stimulation of the type-typical behavior - refers to the stimulation of the type-typical acoustic signaling (“choir singing” in frogs or birds), the imitation of alien sounds and songs in birds corresponds to the invisible imitation manipulation, and, in particular, the development of chicks species-like sounds by imitating adult singing. Еще в 1773 г. английский ученый Д. Баррингтон воспитывал молодых коноплянок совместно с птенцами жаворонков. В результате коноплянки перенимали пение жаворонков. С тех пор аналогичные опыты ставились на птицах многократно.

Что же касается обезьян, то в опытах, поставленных Н. А. Тих на молодых гамадрилах, намечались, правда нечетко, некоторые намеки на возможность выработки даже таких навыков, которые можно было бы квалифицировать как имитационное решение задач на основе звукоподражания (в этих опытах обезьяны получали пищевое подкрепление за подражание звукам, которым в их присутствии обучали других обезьян).

Исходя из приведенной классификации можно определить два принципиально различных подхода к изучению подражания у животных.

Аллеломиметическое поведение изучается путем раздельного обучения изолированных друг от друга животных, которые затем сводятся вместе. Советский зоопсихолог Б. И. Хотин, например, обучал одних животных (рыб, птиц, млекопитающих) реагировать положительно на определенный сигнал, а других — отрицательно. После того как животные были сведены вместе и подвергнуты воздействию этого раздражителя, выяснилось, что преобладает: результаты обычного (неимитационного) научения или взаимная стимуляция. В результате можно судить о силе аллеломиметической реакции, т. е. инстинктивного подражания.

При изучении же имитационного научения животные с самого начала общаются между собой. Одна особь (или несколько особей) выполняет при этом роль «актера», т. е. обучается экспериментатором за соответствующее вознаграждение на виду у других особей — «зрителей». Если в результате последние без собственных упражнений и подкрепления вследствие одних лишь наблюдений за действием «актера» также научаются решать поставленную ему задачу, то можно говорить о факультативном имитационном научении и даже об имитационном решении задач. Так, например, в экспериментах с обезьянами все участвующие в опыте животные устремляются к месту его проведения и внимательно наблюдают, как вожак добывает и получает подкрепление. В итоге соответствующие навыки формируются у всех «зрителей», что проявляется в успешном решении ими той же задачи в отсутствие вожака.

На этом примере видно, как проявляется еще одна особенность, характерная для проявлений подражания в естественных условиях. Дело в том, что наряду с взаимным стимулированием к совместному выполнению определенных (инстинктивных) действий в сообществах животных действует и фактор противоположного рода — подавление действий членов сообщества «господствующими» особями. Так, в приведенном примере обезьяны боялись вплотную подойти к экспериментальной установке, а тем более брать пищу из кормушки. Вместе с тем у обезьян существуют особые «примиряющие» сигналы, оповещающие доминирующую особь о готовности «зрителей» «только смотреть», чем обеспечивается возможность осуществления аллеломиметического поведения и имитационного научения. Отсюда явствует, что явления подражания сложным образом переплетаются с внутригрупповыми отношениями животных.

Подводя итог обзору инстинктивного поведения и научения у животных, вернемся еще раз к описанной ранее общей схеме поведенческого акта. Эта схема, разумеется, не отражает всего многообразия вариантов поведенческих актов в их конкретных проявлениях.

Но во всех этих вариантах остается в силе основная закономерность: каждое действие животного начинается с внутреннего стимула, который в виде потребности активирует животное, кладет начало его поиску раздражителей. Это начало, как и общее направление этого поиска, всегда генетически фиксировано, равно как и конец — заключительные движения животного в завершающей фазе как пройти этот путь от начала до конца между этими «жестко запрограммированными» основными элементами поведения — зависит от лабильных компонентов поведения животного, от его умения быстро и правильно ориентироваться во всех конкретных ситуациях, в которые оно попадает. Как мы видели, особое значение это имеет в начале пути.

У высших животных факультативное научение, сопряженное с формированием операций, является основным средством для продвижения к завершающей фазе. Но поскольку операция направлена на преодоление преграды, т. е. условий, в которых дан объект завершающего поведения, то здесь особенно важна более полноценная по возможности ориентировка животного во времени и пространстве. Ясно, что эта ориентировка будет тем более совершенной, чем выше уровень психической деятельности животного, его познавательные способности. Наибольший эффект обеспечивают в этом отношении высшие психические функции, особенно интеллектуальные способности, придающие всему поведению животного наибольшую гибкость и адаптивность. К этому вопросу мы еще вернемся при рассмотрении эволюции психики.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology