Lecture

Animals exhibit emotions to the same extent as humans, but the list of animals’s emotions is poorer.

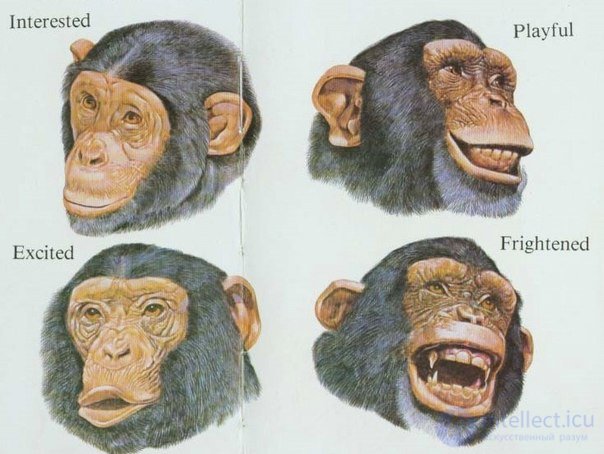

The more developed an organism, the higher its evolutionary level, the more emotions it has, the more complex they are. Emotions develop primarily in herd animals, since they perform primarily a communicative function. Emotions in monkeys are quite developed, they have lively facial expressions and a rich intonational arsenal, while emotions such as moose are very scarce, since, as a predominantly solitary animal, it communicates mainly with the next aspen. Cats, dogs and horses, especially those living with a person, are professors of psychology.

Emotions are animals, and not just animals appear as reactions. To assume that highly organized animals do not use emotions - not true, they actively use them, and how!

Any horse, for example, assesses you from afar: your plastics and facial expressions and instantly determines whether you are going to it, whether you can or a beginner, are afraid of it or not. If you do not forbid fear, the horse will meet you with rage (or fear, if the horse is not angry) and will be selflessly angry (or afraid of you) until you leave its horsebox. If you call a confident person on the place who knows the horses - you can check - the horse stops being angry almost immediately, all the horror stories immediately dissolve.

All the same applies to hunger, thirst, fatigue - if the horses near you are not interested, she remembers that she is hungry, and under this business rolls you to gnaw the nearest dry bush. If you try to explain to her that it is wrong, you will get a lazy animal, dreaming to be left behind. If you get angry, you will get a stubborn donkey, who does not want to budge. If you take the risk of hitting, you will get an animal extremely scared and completely unaware of what it is, or aggressive and evil.

Scared cat

Aggressive cat

It is believed that all or almost all of the actions of animals are explained by instincts. If we talk about the emotions of animals, then their range seems to be narrow: fear and fear, irritation and anger. And feelings of kindness, sadness, hatred and compassion? Are they peculiar to animals? Or, appreciating some of their reactions, we unwittingly want to see in an unusual manifestation of feelings, characteristic of ourselves?

In this paper, we will rely on the research of such scientists as Sherrington, Lange, Hebb, James, Mac Farland, Jean, Griffin, and others.

The relevance of this topic lies in the fact that emotions and feelings are the least developed area of zoopsychology, since fundamental difficulties stand in the way of their research.

Objective: to reveal the facts indicating the presence of emotions in animals and to show the role of emotions in their lives.

Based on this goal, the following tasks were set:

1. To study and analyze literary sources, as well as materials of the World Wide Web on this topic.

2. To show the role of emotions in the life of animals.

3. To reveal the facts testifying to the presence of emotions in animals.

An analysis of the literature on this topic shows that the old anthropocentric theories attribute the ability to feel exclusively to humans, but new experiments prove that higher animals love, enjoy and feel depressed, just like we do.

Emotion, like other types of mental activity, arose and developed in the process of evolution. Consequently, at some stage of evolution, it was an important adaptive factor.

The life of animals, including the ancestors of man, is distinguished by one important feature: the uneven load. The periods of extreme, maximal (and maybe supermaximal) stress alternate with periods of relative rest and relaxation. [1]

In this, apparently, one of the significant differences between animals and representatives of the plant kingdom. Plants produce food with the help of leaves and the root system more or less continuously. If there are oscillations, they are due to photoperiodicity, seasonality, that is, the adaptation of metabolic processes to some external rhythms. But the plant is forever chained to its habitat. And the ability of free movement in space is a property of higher manifestations of life, and it is associated with aperiodicity, with short duration and irregularity of the action of stimuli, with the “impulse” nature of the loads and power. If the plant feeds almost continuously, then the animal has periods of food intake and especially water extremely short. They make up a very small part of the "daily routine" of the animal.

During the hunt and the pursuit of prey, in combat with a strong, life-threatening predator, or at the time of flight from danger from the animal requires a great deal of tension and impact of all forces. Criteria of thrift here are untenable. An animal needs to develop maximum power in a critical situation for it, even if it will be achieved at the expense of energetically unfavorable, uneconomic metabolic processes.

The situation is comparable to the work of the engine of a warship. Its power, say, 30 thousand horsepower, but the design provides for the possibility of forcing up to 50 thousand horsepower. When this happens, rapid engine wear and an excessively large expenditure of fuel. Therefore, in the usual campaign such forcing the engine is not allowed. However, in battle, when it comes to life and death, it is absolutely necessary. In extreme circumstances, the physiological activity of the animal also switches to work in "emergency mode". In this switch the initial physiological and adaptive role of emotions consists. Therefore, evolution and natural selection have consolidated this psychophysiological property in the animal kingdom. [2]

The question arises: why in the process of evolution did not evolve organisms that would constantly work on such "increased capacity"? After all, they would not need the mechanism of emotions to bring the body on alert, as they would always be in a state of "alertness." The answer is clear from the above. Alert state is associated with very high energy costs, with uneconomical expenditure of nutrients. Such animals would need a huge amount of food, and most of it would have been wasted, wasted. It is not profitable for a living organism: it is better to have a low level of metabolism and moderate power, but at the same time to have “emergency mechanisms” that at the right moment will switch the body to function in a different, more intensive mode, that is, they allow you to develop higher power when this is a real necessity. [3]

There is another function of emotions - the signal.

Emotion of hunger causes the animal to look for food long before the depletion of nutrients in the body.

The emotion of thirst drives the animal in search of water, when the reserves of fluid in the body are not yet exhausted, but have already become scanty, have become below a certain "signal" level.

The pain signals the animal that its living tissue is damaged and threatened with death.

The feeling of tiredness and even exhaustion appears much earlier than the end of the energy reserves in the muscles. And if fatigue is removed by a powerful emotion of fear or rage, then the animal’s body is then able to do some very significant work.

Hence, fatigue only signals the animal about the expenditure of a part of its energy resources and the accumulation of their decay products.

As we see, the role of emotions in the life of animals is enormous. This is the biological expediency of emotions as a mechanism for balancing, adapting to the environment.

The word "expediency" should not be confusing and inspire a false conclusion that emotions were supposedly created specifically for some purpose. It is simply that the presence of an emotional mechanism turned out to be beneficial for the animal, and natural selection, acting with irresistible force over many generations, consolidated this property as important and useful. [4] But in some specific situations, emotions can be harmful, coming into conflict with the vital interests of the animal. So, the emotion of rage helps the predator, doubling its strength at the time of pursuit of prey. But the same emotion of rage often leads him to death, depriving him of caution and prudence. Here is a pattern that is inherent in any biological mechanism of adaptation: in general, this mechanism contributes to the survival of the species, but in particular manifestations is not always useful and sometimes harmful. [5]

Healthy animals, running, jumping and playing, feel pleasure and show that they are happy. Dolphin watchers saw how swimming synchronously, jumping and swimming in races, dolphins express the joy of being. Obviously, many animals like to play, and they use every opportunity to play with their own kind. From an evolutionary point of view, you can explain what puppies like to play, because it helps them develop skills that will later come in handy. Nevertheless, it is obvious that they often play simply for the pleasure of playing. A playful animal tries to get another in the game. If another animal refuses, look for another companion for games. If this is not the case, animals are able to play with any thing, and even with their own tail. Sometimes the joy of the game infects others, and the whole pack is included in the game. Ethologist Mark Bekoff watched the elk jumping in the snow, which jumped like an acrobat, tirelessly and with apparent pleasure from the jumps. Despite the fact that it was full of fresh and juicy grass very close, he preferred to have fun in the snow. Even buffaloes love to slide on the ice, uttering joyful lowing. [6]

Elephants can live for about 60 years, during which their teeth change 6 times. Having lost the last tooth (not later than 65 years), they cannot eat and die of starvation. Elephants live in matriarchal families consisting of several adult females and their young, the oldest female in the herd is a matriarch. But their social relationships go beyond the family clan. When two familiar families meet in the savannah, they greet each other with obvious pleasure, moving their ears, touching each other with fangs and making loud sounds with their trunk. The matriarchs greet each other, and each individual joyfully welcomes all friends from another family. Cynthia Moss, who spent 30 years watching a family of wild elephants in Ambrosely (Kenya), writes: "I still get excited every time I see one of the ceremonies of family greetings." “Even when I speak strictly as a scientist, I have no doubts that the elephants rejoice when they see each other again. Maybe this is not the same as human joy, and cannot be equated, but it is elephant joy and it plays a very large role in their social system "[7]

Rats, like humans, release dopamine when they become agitated. In humans, the emotional state is associated with the presence of certain neurotransmitters (molecules that serve to communicate some neurons with others through synapsis). In particular, our states of arousal and satisfaction are characterized by the fact that large doses of dopamine are present in the body. Neuroscientist Steven Silvey discovered that when rats play, their brains release large doses of dopamine. They find the game exciting, and even anticipate it: they are more active and excited when they are carried to the place of the games. However, if they enter a substance that blocks dopamine, this behavior stops. Another neurologist, Jaak Panskepp, discovered that playing rats also produce endorphins, like us. The hormone oxytocin, which plays a role in sexual behavior and attachment among people, is also present in field moles, caring for one another and forming a family. [8]

In fact, love between animals that are not human is not limited to marriage games and sexual intercourse. There are also moments of tenderness, choosing a partner, creating a permanent relationship. Crows "fall in love" and create long-term pairs, as already described by V. Heinrich. Also V.Vursig described the mating games among whales near the peninsula of Valdez, in Argentina. During mating games, the male and female touch each other with their fins, stroke each other, twist the tails, swim together, jump out of the water at the same time. Mother, turned over on his back, raise the cubs on the stomach. The whales even invited observers to join the game, which was already unsafe, and so we had to retire at high speed. In any case, seeing their courtship and constant games, it seemed that they were having a lot of fun. [9]

In addition to joy, animals feel pity, depression and even grief. Ethologists, who spent a lot of time with elephants, like Cynthia Moss and Joyce Poole, learned to recognize the many emotions, even the amazing understanding of death and the expression of grief over the loss of members of the elephant family.

When the elephant dies, the whole herd mourns for several days. According to Cynthia Moss, “it seems that they have a notion of death. Perhaps this is the most amazing feature. Unlike other animals, elephants recognize corpses and skeletons. They do not pay attention to the remains of other animals, but they always react when they see the corpse of an elephant. ” Seeing the remains of an elephant, the whole family stops, their bodies tense. First, they bring their trunks closer to smell the remains, then they touch and move the bones, especially the skull, as if they are trying to recognize the deceased. In some cases, they will find out from the remains of the deceased, and throw the earth and leaves onto the remains.

When an elephant is agonizing, its close ones are near. When he dies, first of all, they will try to revive him, then, when they reconcile themselves to the inevitability, the elephants stay close to the body, gently touching his trunks. After numerous observations of this behavior, Poole argues that "there is no doubt that elephants experience very deep feelings and have some idea of death."

The death of an elephant affects the whole herd. If we are talking about a cub, his mother grieves for several days in a row near the corpse, and even tries to bear him with the help of his trunk and fangs. Other adult members of the group stay close to her and slow down, they can remain for several days with the dead calf, with their heads bowed and their ears hanging down, silent and depressed. Little elephants who have witnessed the murder of their mothers seem to have nightmares, and they wake up screaming. When an adult elephant dies, other elephants try to raise it and do not move away from the body until the body begins to decompose. Sometimes they drive away scavengers from the body and try to cover the body with leaves. The death of the matriarch of the family causes general grief and can lead to the disintegration of the group. This behavior helps hunters and poachers kill elephants. If they kill one representative of the herd, you can do away with the whole herd, because the others not only do not run away, but also try to stay close to the dead. [10]

The English primatologist Jane Goodale, who spent many years among chimpanzees, was able to observe in them emotions and feelings of a different nature, the most extreme curiosity and the most extreme tenderness, the most destructive aggression and grief over the loss of a close family member. One example: Flint, a young and healthy chimpanzee, was very dependent sentimentally on his mother, matriarch Flo, who died at the age of 50 years. Flint was very worried, and was unable to accept her death. He refused to leave his mother’s corpse, sat beside her for a long time, holding her hand and making a plaintive moan. Flint left the corpse only for the night to get into the nest, where he was next to his mother that last night when she died. He remained in the nest, staring at the corpse. He was so depressed that he even rejected the food that his brothers and sisters brought him. He lost weight more and more. Three weeks later, Flint curled up and died.

Not only elephants and chimps mourn. Konrad Lorenz noted that the sadness expressed by geese is very similar to the sadness of children, and also manifests itself: hung head, failed eyes: Females of a sea lion fall into despair when they see their killers devour their killer whales: scream, moan and whine, grieving about their death. Even dolphins, the paradigm of the joy of life, can die from stress, as happens with some specimens during dog training. This led Rick O. Barry, the most famous of these animal trainers, to leave the dressage. [11]

Charles Darwin, who in 1872 published The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, had no doubt that animals possessed feelings. Тщательные наблюдения, проведенные им о разных способах, которыми животные, люди и не люди, выражают эмоции, включая весь репертуар нахмуренных бровей, положения ушей, формы открытия рта, движений хвоста, положение шерсти, положений тела, звуки (мурлыканье, стоны) и другие жесты, наблюдения, которые до сих пор в большей части верны. Действительно, эмоции животных очень прозрачны и мы можем определить их с легкостью, если знаем расшифровывать их знаки.

Собаки и волки выражают свои чувства посредством широкого репертуара поз и звуковых сигналов, а также лицевой мимики и запахом. Волки лают, чтобы оповестить о присутствии чужаков на территории. Собаки, когда засекают присутствие незнакомцев, начинают беспокоиться и оповещают об этом громким и продолжительным лаем. Волки воют, чтобы собрать стаю и направить ее во время охоты. Члены стаи, находящиеся вдали друг от друга, сближаются и начинают выть хором, что усиливает социальные отношения в группе перед атакой. Собаки, оставшись одни, тоже воют, собирая свою «стаю» (их человеческого хозяина). Кроме того, они скулят, когда им причиняют боль, когда они разозлены и в то же время напуганы, они угрожающе рычат. Если их агрессивность увеличивается, они подбирают губы и показывают клыки, не переставая рычать. Движения хвоста тоже очень хорошо передают эмоциональное состояние. Хвост собаки очень выразителен. Когда ей страшно, она поджимает хвост и держит его меж задних ног, не позволяя своим анальным железам выделять сигналы. Таков также жест подчинения, который принимают волки, когда проходят рядом с доминантом. И, наоборот, когда собака чувствует себя уверенно и агрессивно настроенной, она жестко поднимает хвост. Если она довольна, но неуверена (что часто бывает в присутствии хозяина), она мягко повиливает хвостом.[12]

Во время первой половины 20 века психология поведения попыталась применить позитивистский метод в изучении поведения, не рассматривая эмоции. Тем не менее, в последние годы появилось очень большое число книг по этологии и неврологии, которые отвергли исключительно поведенческую методологию и признали чувства у животных.[13]

В 1996 году Сюзан МкКарти и Джефри Массон собрали обширную этологическую документацию в книге «Когда слоны плачут», невролог Жозеф Ле Ду опубликовал «Эмоциональный мозг», строго научное исследование невромеханизмов эмоций. Панксепп начал новую веху в 1998 книгой «Affective Neuroscience: The Foundation of Human and Animal Emotions». В 2000 году появились "Infant Chimpanzee and Human Child: Instincts, Emotions, and Play Habits" (N.Ladygina-Kots and F. De Waal), сравнение чувств и детских игр шимпанзе и человека, и важнейшая антология биолога Марка Бекоффа, «The Smile of a Dolphin: Remarkable Accounts of Animal Emotions», где более чем 50 исследователей представляют результаты своих полевых исследований. Известный журнал Bioscience опубликовал в октябре 2000 г. обширное изучение об эмоциях животных, полное ссылок на многочисленные случаи ситуаций, в которых те проявляли свои чувства. До этого времени эти наблюдения игнорировались специалистами по поведению животных, которые называли их анекдотичными. Но, как указывает Бекофф, «множество анекдотов является фактом». И факты настолько многочисленны, что не могут быть игнорируемы. Согласно представлениям Джеймса Ланге, чувство возникает в результате восприятия изменений своих собственных внутренних органов. Субъективное переживание есть следствие, а не причина мышечных, висцеральных изменений. Но эту теорию простыми опытами опроверг Шеррингтон. Перерезав чувствительные пути, ведущие от внутренних органов в мозг, он прекратил связь внутренних органов с мозгом. При этом эмоциональное поведение не нарушалось. Правда, доводы Шеррингтона тоже вызвали возражения. Автор книги «Организация поведения» Дональд Хебб считает, что опыты Шеррингтона ничего не доказали, так как в них речь идёт об эмоциональном поведении, а не о субъективном переживании. Точка зрения Хебба кажется ошибочной, потому что он неправомерно отрывает эмоциональное поведение животных от эмоционального переживания. На самом деле первое служит вполне адекватным показателем второго. Кэннон экспериментально доказал роль зрительных бугров (таламуса) в формировании эмоций и показал, что эмоциональное переживание возникает при раздражении этих бугров. Бэрд дополнил теорию Кэннона, указав, что субъективное переживание возникает лишь при распространении возбуждения с таламуса на кору головного мозга. В последние годы Линдслей привлёк к объяснению эмоций ещё и ретикулярную формацию (сетевидное образование стволовой части мозга), а Пейпез – лимбическую систему.[14]

Так как животные чувствуют удовольствие и боль, мы можем поставить себя на их место и понять их эмпатически, мы можем сочувствовать им, хотя мы не можем сочувствовать грибу, камню или машине, так как те, не имея нервной системы, не имеют эмоций. Известно, что женщины, в среднем, лучшие наблюдатели, чем мужчины, и более тонко понимают оттенки чужих эмоций. Поэтому неудивительно широкое присутствие женщин среди профессиональных этологов, как приматологи Джейн Гудейл, Диана Фоссей и Бируте Гальдикас, или уже упоминавшиеся Цинтия Мосс и Джойс Пул, изучающие слонов. Женщины проявляют большее сочувствие, большее понимание и нежность к животным и их страданиям. Кроме того, они чаще принимают участие в движениях по защите животных.

В Швеции свиньи, коровы и куры защищены законом.

Французская писательница Маргерит Йорсенер написала большую часть международной декларации прав животных. Шведская писательница Астрид Линдгрен была движущей силой движения, которое привело парламент ее страны провозгласить законы, призванные защитить права коров, свиней и кур. Даже в испанской королевской семье Королева более чувствительна к страданиям животным, чем Король, который нередко присутствует на публичном истязании быков на корридах.

Возрастающее признание учеными эмоций животных и их способности чувствовать удовольствия и муки являются движущей силой, которая приводит в наши дни к моральной революции, затрагивая все аспекты нашего отношения к природе. Очень показателен тот факт, что престижный университет США, Принстон, призвал возглавить новую кафедру этики Питера Сингера, известного защитника прав животных.

In any case, by developing only an artificial, abstract, virtual world, we threaten our roots that connect us with life and a sense of reality.

Summarizing all the above, it should be noted that the tasks set in this work have been completed.

Seven main literature sources devoted to the stated topic were studied and analyzed; In addition, in the course of the work, materials taken from the World Wide Web were developed.

The first chapter of the work shows the role of emotions in the life of animals.

In the second - the facts are revealed, indicating the presence of emotions in animals.

As the main conclusion of this work, it should be noted that there are many facts and observations that speak of a rich palette of emotions in the animal world. And, ultimately, it comes down to a synthesis of these facts, to scientific conclusions. Of course, from the same facts are often drawn a variety of conclusions. Alas, a famous aphorism plays a significant role here: “The result depends on the point of view”. From established views, from conventional wisdom. And sometimes from a false initial position of a scientist. "There is nothing more dangerous for the new truth, like an old delusion." Perhaps these words of Goethe will always be fair in the knowledge of the world. Undoubtedly, the basis of the mental activity of animals is the mechanism of the reflex - the instinctive response of the body to some kind of influence. But do not we see in many cases that which goes beyond the instinct? Often the usual negative answer follows this question. An unusual fact is rejected only because it contradicts the traditional view. And doubts remain, since well-established explanations of unusual cases of animal behavior do not always convince.

1. Godfroy G. What is psychology. In 2 t. T. 1. M .: Mir, 1996. - 496 p.

2. James V. Psychology. - SPb .: Knowledge, 1916. - 240 p.

3. Lange G. Mental movements. - SPb .: Peter, 1996. - 180 p.

4. Luria A. R. Lectures on general psychology. - M .: Mir, 1977. - 320 p.

5. McFarland D. Animal Behavior. - M .: Mir, 1988. - 517 p.

6. Palmer D., Palmer L. Evolutionary psychology. Secrets of the behavior of Homo Sapiens. - SPb .: Prime-Evroznak, 2003. - 384 p.

7. P. Taranov. The Universal Encyclopedia of Arguments. Controversial truths. In 2 tons. T. 2. - Visaginas: Alpha, 2000. - 656 p.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology