Lecture

Congenital and acquired in prenatal behavioral development

Morphofunctional bases of embryogenesis behavior

The behavior of the embryo is in many respects the basis of the whole process of development of behavior in ontogenesis. Both in invertebrates and vertebrates, it has been established that the developing organism produces even in the prenatal (prenatal) period of movement, which are elements of future motor acts, but are still deprived of the corresponding functional value, i.e., cannot yet play an adaptive role in the interaction of the animal with its habitat. This function appears only in the postnatal period of his life. In this sense, one can speak of the preadaptational significance of embryonic behavior.

Academician I.I. Shmalgauzen identified several types of ontogenetic correlations, among which “ergontic correlations” (or functional in the narrow sense), that is, relations between parts and organs due to functional dependencies between them, are of particular interest for understanding the patterns of behavior development. Schmalhausen meant the typical ("final") functions of organs. These are already in the early stages of embryogenesis, for example, the function of the heart or the kidney of the embryo. As a characteristic example of ergontic correlations, Schmalhausen also points to the relationship between the development of nerve centers and nerves and the development of peripheral organs, the sense organs and limbs. With the experimental removal of these organs, the corresponding elements of the nervous system are underdeveloped.

As B. Matveyev established back in the 30s, embryogenesis is characterized by correlative shifts in the ratios between developing organs, which are the result of a violation of the interrelationships of parts of the embryo in a developing organism. As a result, there are functional changes that determine the nature of the activities of the organs being formed.

These findings of leading Soviet zoologists show the complexity of morphofunctional connections and interdependencies that determine the formation of animal behavior in embryogenesis. This was reflected in the concept of systemogenesis P. K. Anokhin. “The development of a function,” said Anokhin, “is always selective, fragmentary in separate organs, but always in the utmost consistency of one fragment with another and always according to the principle of the final creation of a working system.” [43] In particular, with examples of the development of embryos of a cat, a monkey and a human fetus, he showed the functional conditionality of the asynchrony of the development of individual embryonic structures, stressing that "during embryogenesis, there is an accelerated maturation of individual nerve fibers that determine the vital functions of the newborn" (for example, sucking movement), because for its survival "the" system of relations "must be complete by the time of birth." [44]

As the research of A. D. Slonim and his staff showed, intrauterine movements affect the coordination of physiological processes associated with muscular activity, and thereby contribute to the preparation of the behavior of the newborn. According to Slonim, new-born kids and lambs are able, without getting tired, to run up to two hours in a row. This possibility is due to the fact that in the course of embryogenesis, by exercise, coordination of all functions, including vegetative functions, necessary for the implementation of such intensive activity at the very beginning of postnatal development, was formed. In particular, by the time of birth, the regulation of the minute volume of the heart and the respiratory rate, as well as other physiological functions, are already coordinated.

Speaking about the principle of “final creation of a working system” (Anokhin) or embryonic preadaptation of postnatal behavior, i.e. the preadaptive meaning of embryonic behavior, one should not forget about the relativity of these concepts. Fetal preadaptation cannot be understood as a kind of original, “fatal” predestination. The living conditions of an adult animal, its interaction with environmental components ultimately determine the conditions for the development of the embryo, the functioning of its developing organs. The general patterns and the direction of development of the function are determined by the factors established in phylogenesis and genetically fixed.

Fetal learning and maturation

In this connection, it acquires a special question about “embryonic learning,” which was considered by some researchers to be the predominant, if not the only factor in the entire complex process of the initial formation of exosomatic functions. These researchers include the already mentioned well-known American scientist Qing Yang Kuo, who in the twenties and thirties of our century attempted to explain the whole process of forming the behavior of animals solely by the accumulation of motor experience and changes in the environment surrounding the embryo. Kuo was one of the first to convincingly show that already in the course of embryogenesis, the primordial germs of the future organs are exercised, the gradual development and improvement of motor functions through the accumulation of “embryonic experience”.

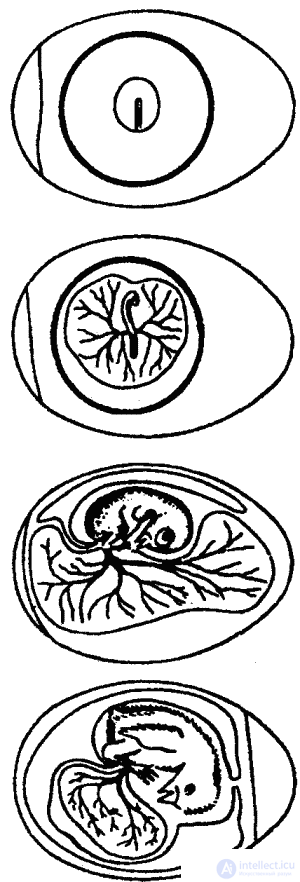

Kuo studied embryonic behavior on many hundreds of chicken embryos (Fig. 18). In order to be able to directly observe the movements of the embryos, he designed and carried out truly virtuoso operations: he moved the embryo inside the egg, inserted windows in the shell, etc. The scientist found that the first movements of the embryo of the chicken, already observed in the fourth, and sometimes in the third the day of incubation is the movement of the head to the chest and away from it. Within a day, the head begins to turn to the sides, and these new movements of the head displace the old ones by the 6–9th day.

Obviously, the reason for this is the lag of the growth of the neck muscles from the growth of the head, which by the tenth day makes up more than 50% of the weight of the entire embryo. Such a huge head muscles can only be rotated, but not raised and lowered. In addition, according to Kuo, head movements are formed under the influence of such moments as its position in relation to the shell, the location of the yolk sac, heartbeat and even the movement of the toes, since the latter in the second half of the incubation period are located to the left and behind the head.

In all this, Kuo saw manifestations of the action of the “anatomical factor” in the development of behavior. Similarly, the specific conditions of morphoembryogenesis, anatomical changes associated with the growth and development of the embryo, influence, in his opinion, the formation of other movements of the chicken embryo. As a result, a chicken hatched from an egg has a whole set of “mechanisms” developed during the period of embryogenesis, but they are not aimed at stimuli that are necessary to sustain life. Broad generalization is characteristic, according to Kuo, both for stimuli (there is no selective attitude towards them, the same reaction follows very different stimuli) and for motor reactions (the whole body always moves, the movements of its individual parts are still poorly or not coordinated at all, they are inappropriate , uneconomical).

From his research, Kuo concluded that the chicken should learn everything, that none of its reactions appear ready-made, and consequently, there is no innate behavior. Forty years after the publication of his first papers, Kuo, clarifying his point of view, pointed out that genetically fixed prerequisites for the formation of behavior may be realized differently depending on the specific conditions of the embryo development, but the decryption of genetic information plays a crucial role in this process. attitude of the embryo to its environment. At the same time, Kuo emphasizes that fetal learning should not be considered in the traditional aspect, since self-stimulation plays a significant role in the development of the behavior of the embryo. However, as shown by the results of modern research, tactile and proprioceptive stimulation, as Kuo imagined it, plays in the development of motility in normal embryogenesis, obviously, a subordinate role.

One-sided approach to the problem of the formation of behavior in ontogenesis, ignoring the innate basis of individual behavior, including at the embryonic stage of development, are, of course, deeply erroneous. If it is possible to talk about some kind of learning in the period of embryogenesis, then it does not occur from scratch, but is the development and modification of a certain genetic germ, the embodiment and realization in the individual life of an individual of the experience gained in the process of evolution. Phylogenesis has prepared the possibility of the development of behavior in ontogenesis in a biologically useful direction for the individual and species. Heredity is manifested not only in the structure of the organism, its systems and organs, but also in their functions.

The hereditary basis for the embryogenesis of behavior is particularly pronounced in those cases where the elements of the behavior of the newborn appear as if in a “finished form”, although the possibility of previous “embryonic learning” is excluded. Obviously, in mammals such cases include searching for the nipple and sucking movements of newborns, sound reactions, etc. Here we can speak only about prenatal maturation of the function without embryonic exercise, that is, without prenatal functional training of the corresponding morphological structures. For such a ripening, it is obviously enough only one congenital development program, which arose and established during the evolution of the species.

A good example showing the presence and role of genetically fixed “action programs” is the behavior of a newborn kangaroo, which is born at such an immature stage of development that it can be compared to an embryo of higher mammals. To a certain extent, we can assume that the final development of the embryo is completed in the mother's bag. But despite the state of extreme immature birth, the cub completely independently moves into the mother's bag, showing amazing motor and orientation abilities. In this case, the bag is located on the basis of negative hydrotaxis (and, possibly, chemotaxis): once outside the birth canal, the newborn, clinging to the wool, rises along dry parts of the bag, finds its entrance, crawls into it, finds the nipple, firmly sticks. to him and it remains a long time to hang on it. The mother's hair is moistened before this on the heels of the body by generic waters spilling from the rupture of the germinal membranes, but the “path” leading to the bag remains dry.

Here a strict sequence of innate reactions attracts attention. At the embryonic stage of its development, which is sharply shortened here, if not interrupted, the young could not learn any individual behavioral acts of this chain, nor this sequence. Before the rupture of the generic membranes, he was constantly in a humid environment and could not, therefore, exercise the negative hydrotaxis behavior. He never touched dry objects, including wool. The situation is similar with other components of this complex behavioral complex, the formation of which is also impossible to explain by “prenatal learning”.

Essential for understanding the processes of maturation of behavioral elements in embryogenesis is the fact that in vertebrates the innervation of the somatic musculature of the trunk and extremities precedes the closure of reflex arcs (in the chicken embryo, this closure occurs already on the 6-7th day from the start of incubation). However, contractions of these muscles begin already from the moment of their innervation and are, therefore, at first non-reflex nature. These movements are rhythmic, as they are caused by spontaneous neurogenic rhythms ("impulse rhythms"). Endogenous rhythm in neuromuscular structures is maintained throughout the life of the animal and is one of the important factors for the maturation of elements of innate behavior.

Nevertheless, it is hardly possible to speak of some kind of “pure” maturation of behavioral acts, especially if we bear in mind the above-mentioned correlative morphofunctional connections. Moreover, it is probably never possible to completely exclude the possibility of the direct prenatal exercise of certain motor elements of a behavioral act. Therefore, objecting to the one-sided postulation of “embryonic learning” as the only factor in the prenatal development of behavior, it is impossible to agree with the opposite extreme point of view, one-sidedly emphasizing the processes of embryonic (and postnatal) maturation. This point of view was formulated by a prominent American investigator of the ontogeny of animal behavior L. Carmichael, who admitted that even in humans the behavior is “nine-tenths” inborn. In either case, the opposition of the innate and acquired in behavior is wrong, which has already been said many times.

As for the term “embryonic learning,” then, obviously, the expression “embryonic training” will be more accurate, at least when it comes to the early stages of embryogenesis. In the first stages, as already mentioned, there are not even reflex arcs yet; it is doubtful that conditioned-reflex connections are formed at the middle stages of embryogenesis. Obviously, there are no habituation phenomena at these stages. However, in each case, the functioning of a developing organ or system, of course, is an individual “assimilation” and “adjustment” of the species experience, i.e., instinctive behavior, in the form of training. The latter, of course, also belongs to the category of learning as one of its elementary forms. The full-fledged learning, as will be shown later, is found only at the final stages of embryogenesis.

Comparative review of the development of motor activity of embryos

Invertebrates

The embryonic behavior of invertebrates is still very poorly understood. The few information that has so far been obtained are mainly related to the annelids, mollusks, and arthropods. It is known, for example, that embryos of cephalopod mollusks, already in the early stages of their development, rotate inside the egg around their axis at a rate of one revolution per hour. In other cases, the embryos move from one pole of the egg to the other. All these movements are carried out with the help of cilia, which is of particular interest, given that this primitive method of movement in adult cephalopods is absent, but is widespread among marine invertebrate larvae.

It also deserves attention that by the end of the invertebrate embryogenesis, some instinctive reactions, which are of paramount importance for survival, are already fully formed. In mysids (marine crustaceans), for example, by the time of hatching, the avoidance reaction, that is, evasion from adverse effects, is already well developed. But, as the Canadian researcher M. Burrill showed, initially the embryo has a spontaneous “startle” and “twitch”, which then more and more often arise in response to a touch to the egg. Thus, the initially spontaneous movements are gradually replaced by reflex movements.

Other crustaceans - sea goats (detachment of scraplings) - from the 11th to the 14th day of development, i.e. before hatching, spontaneous and rhythmic movements of the head and other parts of the embryo are observed, from which the specific motor responses of these crustaceans are subsequently formed. Only at the end of embryogenesis, on the day of hatching, motor responses to tactile irritations appear (when a hair touches the embryo, from which an egg shell was removed in the experiment). Under natural conditions, the entire set of movements of an adult individual is found already 10 hours later after hatching.

In the daphnia embryo, the antennas serving in adults for swimming begin to move in the middle stages of embryogenesis, and before its completion they rise and take on the position that is necessary to perform the swimming movements. At this time (a few hours before leaving the egg) antennas begin to move particularly intensively.

In these examples, the gradual formation of a reflex response on the basis of initially endogenously conditioned movements, which are subsequently associated with external stimuli, partly by means of "embryonic learning", is clearly manifested. This process is associated with deep morphological transformations.

Lower vertebrates

The first movements of fish embryos, according to a number of researchers, also arise spontaneously on an endogenous basis. As far back as the 1920s, it was shown that the movements of the organ primordia appear in a strict sequence, depending on the maturation of the corresponding nervous connections. After the appearance of sensory nerve elements, exogenous factors (for example, touch), which are combined with genetically predetermined coordination of movements, also begin to influence the behavior of the embryo. Gradually, initially generalized movements of the embryo differentiate.

Вообще у зародышей костистых рыб обнаруживаются к концу эмбриогенеза такие движения: дрожание, подергивание отдельных частей тела, вращение, змеевидное изгибание. Кроме того, перед вылуплением производятся своеобразные «клевательные» движения, облегчающие выход из яйцевидной оболочки. Кроме того, выклеву способствуют и изгибательные движения тела. В ряде случаев удалось установить четкую связь между появлением новых двигательных актов и общим анатомическим развитием.

Сходным образом совершается формирование эмбрионального поведения и у земноводных. Из первоначально генерализованного сгибания всего тела зародыша постепенно формируются плавательные движения, движения конечностей и т. д., причем и здесь двигательная активность развивается первично на эндогенной основе.

Интересный пример представляет в этом отношении жаба Eleutherodactylus martinicensis с острова Ямайка, у которой выход из икринки как бы задерживается и личинка развивается внутри яйцевых оболочек. Тем не менее у нее проявляются все движения, свойственные свободноплавающим личинкам (головастикам) других бесхвостых земноводных. Как и у последних, плавательные движения формируются у этой личинки постепенно из более генерализованных двигательных компонентов: первые движения конечностей еще слиты с общим извиванием всего тела, но уже спустя сутки можно вызвать одиночные рефлекторные движения одних конечностей независимо от движений мышц туловища; несколько позже и в строгой последовательности появляются более дифференцированные и согласованные движения всех четырех конечностей, и наконец возникают во всех деталях вполне координированные плавательные движения с участием всех соответствующих моторных компонентов, хотя плавать сформировавшаяся к этому времени личинка еще не начинала, ибо она по-прежнему заключена в яйцевые оболочки.

Что же касается хвостатых амфибий, то Когхилл показал в свое время, что эмбрион амбистомы производит плавательные движения еще задолго до вылупления, изгибаясь сперва наподобие буквы «С» и позже как буква «S». Еще позже появляются движения ног, типичные для передвижения по суше взрослой амбистомы, причем нейромышечная система, детерминирующая первичные плавательные движения, определяет и эти локомоторные элементы, особенно последовательность и ритм движений. Кармайкл сумел на этом же объекте доказать, что этот механизм созревает без научения. Он вырастил эмбриона амбистомы в анестезирующем растворе ацетонхлороформа, который полностью обездвиживал зародыш, но не препятствовал его росту и морфогенезу. В таких условиях локомоторные способности развивались вполне нормально, и в итоге они не отличались от таковых контрольных организмов, развитие которых совершалось в обычных условиях. Из своих опытов Кармайкл вывел заключение, что формирование способности к плаванию не нуждается в процессах научения, а зависит исключительно от анатомического развития.

Однако, как справедливо отмечал по поводу этих опытов польский зоопсихолог Я. Дембовский, у подопытных эмбрионов подавлялись лишь мышечные движения, возможность накопления двигательного эмбрионального опыта, но не другие функции, в частности процессы в развивающейся нервной системе. Невозможно, как пишет Дембовский, создать такие экспериментальные условия, при которых нервная система развивалась бы, не функционируя. Поскольку нервная система начинает функционировать еще до того, как она окончательно сформировалась, это функционирование также является своего рода упражнением, которое в свою очередь является важным фактором развития нервной деятельности, а тем самым всего поведения зародыша.

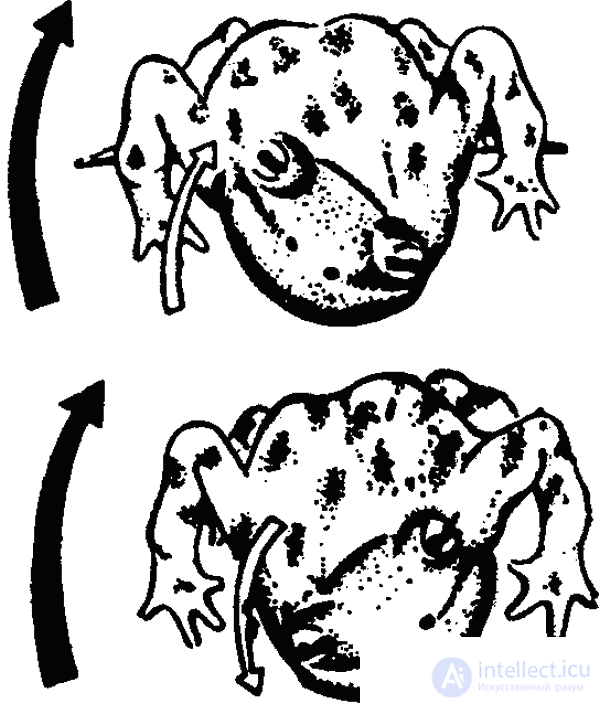

Для выявления эндогенной обусловленности формирования двигательной активности зародышей производились интересные опыты на эмбрионах саламандр: пересаживались зачатки конечностей таким образом, что последние оказывались повернутыми в обратную сторону. Если бы формирование их движений определялось эмбриональным упражнением (путем афферентной обратной связи), то в ходе эмбриогенеза должна была бы произойти соответствующая функциональная коррекция, восстанавливающая способности к нормальному поступательному движению. Однако этого не произошло, и после вылупления животные с повернутыми назад конечностями пятились от раздражителей, которые у нормальных особей обусловливают движение вперед. Сходные результаты были получены и у эмбрионов лягушек: перевертывание зачатков глазных яблок на 180° привело к тому, что оптокинетические реакции оказались у этих животных смещенными в обратном направлении (рис. 19).

Все эти данные приводят к заключению, что формирование в эмбриогенезе локомоторных движений и оптомоторных реакций (а также некоторых других проявлений двигательной активности) происходит у низших позвоночных, очевидно, не под решающим влиянием экзогенных факторов, а в результате эндогенно обусловленного созревания внутренних функциональных структур.

Birds

Эмбриональное поведение птиц изучалось преимущественно на зародышах домашней курицы. Уже в конце вторых суток появляется сердцебиение, а начало спонтанной двигательной активности куриного эмбриона приурочено к 4-му дню инкубации. Весь период инкубации длится три недели. Движения начинаются с головного конца и постепенно простираются к заднему, охватывая все большие участки тела зародыша. Самостоятельные движения органов (конечностей, хвоста, головы, клюва, глазных яблок) появляются позже.

Как уже говорилось, Куо установил наличие и показал значение эмбриональной тренировки у зародыша курицы (а также других птиц), но впал при этом в односторонность, отрицая наличие врожденных компонентов поведения и спонтанной активности как таковой. В дополнение к сказанному приведем еще несколько примеров из работ этого выдающегося исследователя.

Куо установил, что максимальная двигательная активность эмбриона совпадает по времени с движениями амниона, т. е. внутренней зародышевой оболочки, обволакивающей зародыш. Из этого Куо заключил, что пульсация оболочки обусловливает начато двигательной активности последнего. Впоследствии, однако, В. Гамбургером было показано, что нет подлинной синхронизации между этими двигательными ритмами, а Р. В. Оппенгейм экспериментально доказал, что движения эмбриона не только не зависят от движения амниона, а, возможно, даже сами обусловливают их.

The formation of pecking movements, according to Kuo, is primarily determined by the rhythm of the embryo's heartbeat, for the first movements of the beak, its opening and closing, are performed synchronously with the contractions of the heart. Subsequently, these movements are correlated with bending movements of the neck, and shortly before hatching, the attractive act follows any irritation of the body in any part of it. Thus, the pecking reaction formed by embryonic training has a very generalized character at the time of hatching. The “narrowing” of the reaction in response to the action of only biologically adequate stimuli occurs in the first stages of postembryonic development. According to Kuo, this is the case with other reactions.

Важную роль в формировании эмбрионального поведения Куо отводил также непосредственному влиянию среды, окружающей зародыш, и происходящим в ней изменениям. Так, например, у куриного зародыша начиная с 11-го дня инкубации желточный мешок начинает надвигаться на брюшную сторону зародыша, все больше стесняя движения ног, которые до вылупления сохраняют согнутое положение, причем одна нога располагается поверх другой. По мере того как желток всасывается зародышем, верхняя нога получает все большую свободу движения, однако находящаяся под ней нога по-прежнему лишена такой возможности. Лишь после того как верхняя нога получит возможность достаточно далеко отодвигаться, нижняя может начать двигаться.

Таким образом, движения ног развиваются с самого начала не одновременно, а последовательно. Куо считал, что именно этим определяется развитие механизма последовательных движений ног цыпленка при ходьбе, что здесь кроется первопричина того, что вылупившийся из яйца цыпленок передвигается шагами, попеременно переставляя ноги, а не прыжками, отталкиваясь одновременно обеими лапками. Поддерживая концепцию Куо, Боровский писал по этому поводу, что «цыпленок шагает не потому, что у него имеется „инстинкт шагания“, а потому, что иначе не могут работать его ноги и их механизм, выросшие и развившиеся в таких именно условиях. Механизм этот не появится как нечто готовое в тот момент, когда он понадобится, а развивается определенным путем, под влиянием других факторов». [45]

Kuo's many mechanistic concepts did not withstand the experimental test produced by later researchers, others still need such a test, especially since the correlative relationships revealed by him do not necessarily indicate causal relationships. It was not confirmed, in particular, Kuo's opinion that the leading factor in the motor activity of the embryo in early embryogenesis is heartbeat.

Гамбургером и его сотрудниками было установлено, что уже на ранних стадиях эмбриогенеза движения зародыша имеют нейрогенное происхождение. Электрофизиологические исследования показали, что уже первые движения обусловливаются спонтанными эндогенными процессами в нервных структурах куриного эмбриона. Спустя 3,5–4 дня после появления первых его движений наблюдались первые экстероцептивные рефлексы, однако, Гамбургер, Оппенгейм и другие показали, что тактильная, точнее, тактильнопроприоцептивная стимуляция не оказывает существенного влияния на частоту и периодичность движений, производимых куриным эмбрионом на протяжении первых 2–2,5 недель инкубации. По Гамбургеру, двигательная активность зародыша на начальных этапах эмбриогенеза «самогенерируется» в центральной нервной системе.

Гамбургером производился следующий опыт: перерезав зачаток спинного мозга в первый же день развития куриного эмбриона, он регистрировал впоследствии (на 7-й день эмбриогенеза) ритмичные движения зачатков передних и задних конечностей. Нормально эти движения протекают синхронно. У оперированных же эмбрионов эта согласованность нарушилась, но сохранилась самостоятельная ритмичность движений.

Это указывает на независимое эндогенное происхождение этих движений, а тем самым и соответствующих нервных импульсов, на автономную активность процессов в отдельных участках спинного мозга. С развитием головного мозга он начинает контролировать эти ритмы. Вместе с тем эти данные свидетельствуют о том, что двигательная активность не обусловливается исключительно обменом веществ, например, такими факторами, как уровни накопления продуктов обмена веществ или снабжения тканей кислородом, как это принималось некоторыми учеными.

When studying the embryonic development of the behavior of birds, it is necessary to take into account the specific features of the biology of the studied species, which are also reflected in the course of embryogenesis. This is especially true of the differences between brood (mature bred) and chick (non-breeding) birds. So, for example, as the Soviet researcher D. N. Hoffman has shown, in comparison with the chicken, the rook develops more rapidly, the body mass of the embryo accumulates faster, but in the hen the embryogenesis proceeds more evenly and there are more periods of growth and differentiation. The last period of the formation of morphological structures and behavior takes place in the hen still inside the egg, while in the rook the same (as a non-mature bird) this period refers to postembryonic development.

Mammals

In contrast to the animals examined so far, mammals embryos develop in the womb, which significantly complicates (and already very difficult) the study of their behavior, therefore much less data is accumulated on the embryonic behavior of mammals than on the chicken embryo and embryos of amphibians and fish. Direct visual observations are possible only on embryos extracted from the maternal organism, which sharply distorts the normal conditions of their life. X-ray studies indicate that the motor activity of such artificially isolated embryos is higher than normal. However, it was precisely at such sites, mainly rodent germs, that the data that we have today were obtained.

For example, according to Carmichael, the development of motor activity takes place in the guinea pig embryo as follows. The first movements consist in twitching of the neck and shoulder area of the body of the embryo. They appear approximately on the 28th day after fertilization. Other very diverse movements gradually appear, and by the 53rd day, that is, approximately a week before birth, distinct reactions are formed that reach maximum development several days before birth. Such an embryo already reveals quite adequate, and most importantly, modifying reflex responses to tactile irritations: touching the hair to the skin near the ear causes a specific twitch of the latter, continuous continuation of this irritation or its repeated repetition - bringing the limb of this side to the stimulus, which often results in its removal ; if after that continue irritation, then the whole head, and then the body of the embryo, begins to move, which can lead to its rotation, and finally, according to Carmichael, "every muscle is put into action." Carmichael said on this occasion that the embryo behaves as if according to a proverb: “if you don’t immediately succeed - try, try again”, but stressed that there is no reason to assume that anything in this behavior is learned.

The embryonic development of mammals is significantly different from that of other animals. This difference is expressed in the fact that in mammals the movements of the extremities are formed not from the initial general movements of the entire embryo, as we have seen in the above-mentioned other vertebrates, especially the lower ones, but appear simultaneously with these movements or even before them. It is likely that early afferentation became more important in mammalian embryogenesis than spontaneous endogenous neurostimulation.

The constant close connection of the developing embryo with the maternal organism, in particular by means of a special organ, the placenta, creates in mammals quite special conditions for the development of embryonic behavior. A new and very important factor in this respect is the possibility of influencing this process from the maternal organism, primarily through the humoral path.

This possibility is indirectly indicated by the results of experiments in which the female embryos of the guinea pig were affected by the male sex hormone (testosterone) even during their prenatal development. As a result, when they became sexually mature, they showed signs of masculine behavior to the detriment of the sexual behavior characteristic of normal females. A similar effect produced after birth did not give such an effect. Similarly, it was possible to transform and sexual behavior of males. Obviously, during embryogenesis, the content of testosterone in the body of the embryo affects the formation of central nervous structures that regulate sexual behavior: its absence in the direction of female signs, its presence in the direction of male.

In experiments of a number of studies, pregnant females of rats occasionally caused states of anxiety. In such conditions, more timid and excitable young were born than normal, despite the fact that they were then fed by other females that were not subjected to experimental influences. These data particularly clearly show the role of the influence of the maternal organism on the formation of signs of the behavior of the baby in the embryonic period of its development.

Prenatal development of sensory abilities and communication elements

The effect of sensory stimulation on the embryo's motor activity

Above are examples of reflex movements of embryos, produced primarily in response to tactile stimuli. Sensomotor activity is a single process at all stages of the animal's life, although, as we have seen, the motor component is primary in embryogenesis and can occur on an endogenous basis. At the same time, as the embryo develops and its receptor systems form, sensory stimulation is becoming increasingly important, apparently also in the form of self-stimulation.

Kuo saw such self-stimulation, in particular, in that the chicken embryo touches one part of the body (for example, a leg or wing) to another part (for example, the head) and thereby causes the motor reaction of the latter. Oppenheim, although referring to his own research and the work of other authors, questions the validity of Kuo’s conclusions about such a mechanism of self-stimulation, but does not deny the existence of embryonic sensorimotor connections, as well as the meaning of sensory stimulation in embryonic behavior.

As early as the beginning of the 1930s, D.V. Orr and VF Windle were able to show that, along with spontaneous motor activity, a chicken embryo develops a reflex system of movements. Isolated wing movements occur in response to tactile stimulation already in the early stages of embryogenesis; this indicates that the potential possibilities of reflex reactions exist already when there are no real possibilities of external affectation and the motor activity of the embryo is manifested only in general spontaneous gestures. The same scientists found that in the chicken embryo the motor structures of the nervous system are formed before the sensory, and the first reactions to external stimuli appear only four days after the first spontaneous movements.

However, sensory stimulation acquires the greatest importance in the chicken embryo at the last stages of embryogenesis, 3–4 days before hatching (Hamburger). It was during this period that the development of behavior in birds included as powerful external factors, optical and acoustic stimuli that prepare chicks for biologically adequate communication with their parents.

The development of vision and hearing in avian embryos

Sight and hearing appear only at the end of embryogenesis and do not affect the development of the early motor activity of the embryo. True, as was established by a number of Soviet researchers (T. P. Blinkova, G. E. Sviderskaya and others), strong external stimuli can cause reactions of the chicken embryo already at the middle and even early stages of embryogenesis. Reactions to loud sounds are detected not only after the 14–19th day, when the organ of hearing begins to function, but even starting from the 5th day of incubation. At the same time, you can cause reactions and powerful light effects. All these reactions are expressed in the strengthening or inhibition of embryonic movements. However, not to mention that in these experiments, the embryos were subjected to extreme, biologically inadequate influences, light and sound can act at this stage only as physical agents that directly affect muscle tissue or skin, but not as carriers of optical or acoustic information.

If, as it appears from the new data of the American scientist G. Gottlieb, to influence the embryo with biologically adequate, i.e., sounds that are usually found in nature at such a stage when it does not react to such irritations, then this may have a positive effect on the emerging later hearing reactions of the embryo.

With regard to the development of optical reactions, it is only from the 17th – 18th day of incubation that electrophysiological changes are observed in the eye and in the visual segments of the chicken embryo in response to optical stimuli. In the Peking Duck embryo, for example, the pupillary reflex appears on the 16th day of incubation, but this is a purely photochemical reaction that has no functional significance and changes to the 18th day (that is, relatively earlier than that of the chicken embryo). reaction. Obviously, by this time the peripheral and central-nervous elements of the visual analyzer are already functioning. Before hatching chicks, the pupillary reflex is almost as developed as in the adult duck.

The development of acoustic contact between embryos and parents in birds

In embryos of many birds in the last days before hatching, not only distant receptors begin to function, that is, organs of sight and hearing, but also the first active actions appear directed at the external environment, namely, giving signals to the incubating parents. Thus, for example, a representative of the squad of chistikov kaira learns to nest another 3-4 days before hatching to distinguish the voice of the parent from the voices of other kayr nesting in close proximity in the bird bazaars. If the pre-incubated eggs play the tape recordings of a particular adult murre, and then play this recording simultaneously with the recording of the other murre's shouting before the chicks hatching from these eggs, they will be directed towards the sounds that they heard before hatching. Control chicks from “unvoiced” eggs will go between the sources of sounds, and then start to rush between them. It was found that the recognition of the parental voice (as opposed to the voices of neighboring birds) is carried out on the basis of matching the rhythms of feeding the sounds of the parent and the non-hatched nestling: in response to the last squeak, the incubating bird rises, moves the egg and voices itself. Thus, the kinesthetic sensations of the embryo are combined with acoustic, and in general, its activity coincides with that of an adult bird, which allows us to establish the identity of the heard sound of the parent (research B. Chanz).

In this example, we see how the inborn, instinctive behavior (locomotor response of nestlings hatched in isolation to a species-specific sound, i.e., a key stimulus) matured in embryogenesis, is combined with a true embryonic learning (conditioned-reflex), which results in individual recognition prenatal period of development, differentiation of individual differences of type-specific sounds. It is in this direction that the corresponding inborn triggering mechanism of the chick is completed, its enrichment with the necessary additional features through learning (in this case, prenatal). We will still meet with this issue when considering the sealing process. Now it is important for us to note that there is an exchange of signals between the embryo and the parent individual, and primary communication occurs.

Similar results were obtained in other species of birds, including a close relative of the guinea fawn. Prenatal recognition of the voices of parents was also found in goose (Canadian brant), sandpipers (sandpiper), and representatives of other groups of birds. In particular, a comparison of the behavior of chicks bred in an incubator under sound isolation with that of chicks who heard the cries of adult birds of their own species shortly before hatching, showed the essential importance of embryonic learning in gulls. A German researcher M. Impekovin found that changes in the behavior of adult gulls (Larus atricilla) during the transition from hatching to caring for chicks are largely due to acoustic signals given by chicks before hatching. With such sounds, the incubating bird begins to glance down at the eggs, alternately get up and sit down, roll the eggs, dust off and make reciprocal cries. These reactions could be triggered by reproducing the sounds produced by the chick in a “pure form,” that is, in a tape recording. With their slow playback, that is, changes in the physical parameters of sounds, the reactions of the parent individual weaken and appear less frequently. On the other hand, Impekovo was able to experimentally prove that parental cries, heard by chicks before hatching, stimulate the biting movements of the latter, including the postnatal pecking of the beak of the parent, i.e., begging. Thus, the stimulating influence of parental cries is manifested here as the result of prenatal accumulation of experience.

Embryogenesis and the development of mental reflection

As can be seen from the above, in the embryogenesis intensive preparation takes place for the subsequent, postnatal stages of behavior formation, and in part the formation of the behavior elements of the newborn through, on the one hand, the development of genetically determined components of activity and, on the other hand, the accumulation of embryonic experience. As in the postnatal life of an animal, these two sides of a single process of behavioral development - innate and acquired - cannot be separated from each other and studied outside their relationship, therefore it is wrong to consider the embryogenesis of behavior from the alternative point of view: maturation of innate elements of behavior or embryonic exercise. In each case, we can talk only about which of these components prevails or even dominates. And here the effects of various factors in different ratios and combinations are intertwined in a complex way, as it happens at the postnatal stage of development.

It is necessary, of course, to take into account the specific features that distinguish the prenatal development of animal behavior. This applies primarily to the role of the environment in the formation of prenatal motor activity and mental activity.

The data presented above show that the development of behavior in the prenatal period of ontogenesis takes place in lower and higher animals unequally, although it reveals a number of common features. These phylogenetic differences are due to the laws of the evolution of embryogenesis, established primarily by Severtsov, as already mentioned above. But in general, it can be said that in all animals, at least in the early stages of embryogenesis, the direct environmental influences play a minor role (or no role at all) in the formation of individual forms of motor activity.

The environment in which the mammalian embryo develops is the maternal organism, which not only stores and protects it from adverse effects, but also directly provides for all its vital activity. Therefore, the womb is the habitat of the embryo to which its activity is directed. However, the connection of the embryo with the genuine external world, in which the whole postnatal life of a developing organism takes place, is carried out only indirectly through the mother's organism and cannot be essential for the development of the mammalian psyche in the prenatal period of its development.

Unlike mammals and, probably, other viviparous animals, during extrauterine development, the embryo is often exposed to various environmental agents. However, as already noted, experimental studies have shown that these agents can hardly directly direct the development of the primary forms of embryonic motor activity. But even if we assume the opposite, namely that such effects are able to directly influence the formation of this activity, such a link would necessarily be one-sided, because the scope of the embryo's motor activity does not extend beyond the egg membranes and cannot cause physical changes in the environment. But this means that there is no essential source of mental activity.

Another circumstance that extremely limits the development of the psyche in the embryonic period of development is the homogeneity, constancy and poverty of the components of the environment that surrounds the embryo, both in the egg (bird or egg) and in the womb of a mammal. There he practically has nothing to reflect. Поэтому будет, очевидно, правильно сказать, что психика эмбриона — это психика в процессе ее становления. Эмбрион — это еще не полноценное животное, а формирующийся организм животного на начальном этапе своего развития. Животная жизнь невозможна без активного взаимодействия с внешней (т. е. постнатальной) средой, а как раз это взаимодействие еще отсутствует на эмбриональном этапе развития, по меньшей мере на его ранних стадиях. В ходе эмбриогенеза осуществляется лишь подготовка к этому взаимодействию.

На ранних стадиях эмбриогенеза формируются предпосылки, потенциальные возможности психического отражения, т. е. существуют только зачаточные формы элементов психики. Лишь по мере того как формируются органы и системы органов развивающегося организма и появляется необходимость установления и расширения связей с внешним миром, зарождается и развивается психическое отражение, которое является функцией этих структур и служит установлению этих связей.

Как было показано, это происходит в конце эмбриогенеза, во всяком случае у птиц, у которых наряду с весьма дифференцированной двигательной активностью (и на ее основе) появляется коммуникативное поведение, обеспечивающее установление контактов с внешним миром (конкретно — с родительской особью) еще до вылупления.

Во взаимосвязях между невылупившимся птенцом и родительской особью, в согласовании их поведения на протяжении последних дней инкубации проявляется уже достаточно сложная психическая деятельность эмбриона. Правда, это относится лишь к заключительной стадии пренатального онтогенеза. При этом необходимо также учесть, что такая психическая активность зародыша едва ли свойственна млекопитающим, у которых эмбриональное развитие является по сравнению с птицами относительно укороченным: детеныши рождаются на более ранних стадиях эмбриогенеза, на которых можно предположить наличие лишь примитивных элементов будущей психической активности.

Итак, можно сказать, что значение эмбриогенеза для формирования психической деятельности состоит в том, чтобы подготовить морфофункциональную основу психического отражения. Это относится как к двигательным компонентам психической деятельности, так и к подготовке условий для функционирования сенсонейромоторных систем на постэмбриональном этапе развития.

Ясно, что будет поздно, если эти предпосылки начнут формироваться лишь после появления животного на свет, поэтому такая база должна уже существовать к началу постнатального развития, чтобы организм мог приступить к построению всесторонних отношений с компонентами среды его обитания. Для подготовки этой базы достаточна генетически фиксированная спонтанная двигательная активность эмбриона, дополняемая более или менее выраженным эмбриональным научением. Такая активность может формироваться и в той константной, однообразной, нерасчлененной, бедной предметными компонентами среде, в которой живет и развивается зародыш.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology