Lecture

Instinctive behavior as the basis of animal life

As was shown, instinctive behavior and learning do not exist in real behavior by themselves, but only together, intertwining with each other in a single behavioral act. However, this does not mean that instinctive behavior or learning is merely conventions, artificially created for scientific analysis. Here, only their separation is conditional, these components themselves really exist and function as clearly distinguishable life processes with their specific qualitative features.

In modern scientific research, the concept of “instinct” is increasingly avoided due to the diversity and vagueness of its interpretation. Understood as innate, hereditarily fixed, type-typical "instinctive behavior" consists of instinctive actions or acts, which in turn consist of individual instinctive movements (or postures, sounds, etc.). A clear distinction between these terms is necessary for ethological analysis of the category of animal behavior under discussion.

When we say that behavior is a combination of the functions of external, “working” organs of the animal organism, it is necessary to distinguish these functions themselves and their orientation in time and space. Both are instinctively based. Learning can only change the orientation of these functions. This means that no learning can be made to function the organs of an animal otherwise than due to their genetically fixed structure. It is morphological features that determine the nature of the functioning of exosomatic organs, i.e., instinctive movements. It is impossible, contrary to the saying, to teach the hare to light a match, because it does not have the corresponding morphofunctional prerequisites in the structure of its limbs. But you can teach a hare to use its limbs in a natural (instinctive) way at the right time and in a certain direction, i.e., to orient its instinctive movements in time and space by learning (in this case, training).

What has been said should not be understood in the sense that in the behavior in general the structure and structure are primary, and the secondary is function, movement. On the contrary, we are talking about the primacy of motion, function, bearing in mind that the function determines the form. Biological conditionality of behavior does not mean its morphological conditionality; especially in historical, phylogenetic terms. In the process of evolution, undoubtedly, behavior determined the formation of morphological features necessary for the more successful implementation of the behavioral acts themselves.

But when we talk about specific instinctive movements - the results of the evolutionary process, we mean the functions of these morphological formations and the fact that the form of performing behavioral functions is determined by the corresponding morphological structures. Specifically, this means that each animal can move or eat only as it is determined by the specific structure of its external organs that serve to perform these functions.

Considering all this, we can say that all the vital activity of the animal organism, manifested in external activity, is based on instinctive movements and other instinctive reactions (thermal, electrical, color changes, secretions, etc.). They provide all the vital functions of the body, metabolic processes, and thus the existence of an individual and reproduction. That is why we are talking about the primacy of instinctive movements in relation to nervous activity, sensation, mental reflection, which serve in animals only for the realization of these movements, for their orientation. Therefore, in evolutionary terms, the development of the psyche was a necessary consequence (and then already a prerequisite) of increasing the level of metabolism and motor activity.

Instinctive behavior is not exhausted, however, by the functions of the exosomatic organs themselves, but includes the mechanisms of their adjustment and space-time orientation. In this regard, the adjustment and orientation carried out by the acquired way, based on learning, are important, but still only an addition to these instinctive processes.

Internal factors of instinctive behavior

As already mentioned, the problem of instinct and learning is directly related to another equally important problem - the problem of internal and external factors, behavior motivation.

For a long time it was believed that instinctive actions are determined by internal, and moreover mysterious, causes, while individual learning depends on external stimuli. In this form, the ideas of the exceptional or even the overwhelming significance of internal or external factors are already found among ancient thinkers. At the same time, the mystical, teleological approach was based on the premise of the initial expediency of purely internal, transmitted from generation to generation factors. The mechanistic approach, which has received particular development since the time of Descartes, recognized only external factors as driving forces of behavior. In a number of cases, both views irreconcilably defended up to our century.

What do we know today about motivation, about the driving forces of instinctive behavior, and thus about behavior in general? We turn first to the internal factors that give the first impetus to any behavioral act, without going into the details of the very complex physiological processes that have been studied in this connection over the past decades.

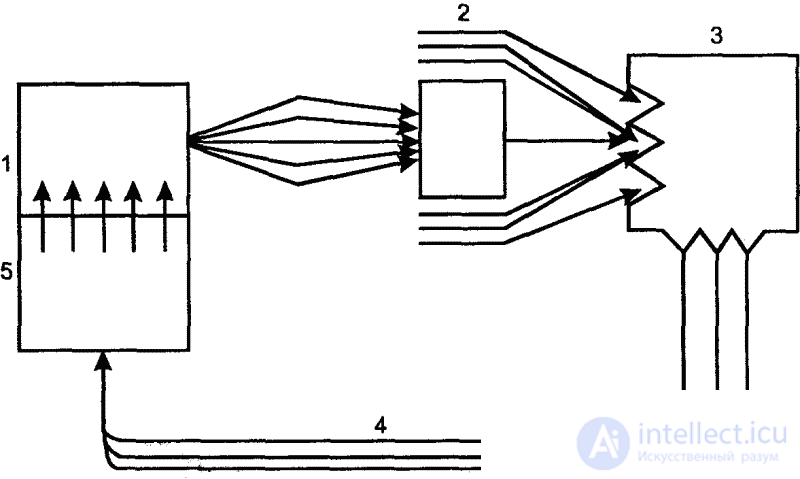

The internal environment of the animal organism is continuously updated, but, despite the ongoing processes of assimilation and dissimilation, this environment remains constant in its physiological indicators. The stability of the internal environment is an absolutely necessary condition for the vital activity of the organism. Only under this condition can the necessary biochemical and physiological processes be carried out. Any, even minor, deviations from the norm are perceived by the interoreceptor system and trigger the physiological mechanisms of self-regulation, as a result of which these disorders are eliminated. The Soviet physiologist Academician P.K. Anokhin considered such complex mechanisms of self-regulation to be complex dynamic structures that function according to the principle of feedback (inverse afferentation) and designated by him as functional systems (Fig. 5).

So, the constancy of the internal environment is based on the self-restoring balance of the internal processes of the body. An important feature of these processes is that they proceed in the form of rhythms, which are also built on self-regulation systems. In the shifts of these rhythms, the prominent Soviet zoopsychologist V. M. Borovsky, in the 1930s, saw the primary motivation of behavior. Speaking against the idealistic understanding of instinctive behavior, he showed that the motivation of this behavior, that is, in what is commonly called impulses or impulses, there is nothing supernatural, divorced from the material world. Internal motivation, he emphasized, is always a shift in the correlation of physiological rhythms in the body towards the establishment of the most advantageous correlation of rhythms of all physiological processes under given conditions. In this constant restoration of internal equilibrium, Borovsky saw the basis for the viability of organisms.

So, the root cause and the basis of the motivation of behavior are more or less significant and long-term deviations from the normal level of physiological functions, violation of internal rhythms that ensure the vital activity of the organism. These shifts are expressed in the emergence of needs, to the satisfaction of which the behavior is directed.

Of primary importance for internal motivation of behavior are the rhythmic processes occurring in the central nervous system. The proper rhythm of its stem in vertebrates and abdominal nerve structures in invertebrates provides, above all, orientation of behavior over time. Now autonomous, self-excited oscillatory processes ("internal" or "biological, hours") that regulate the overall rhythm of the vital activity of the body are well known. With regard to behavior, this means that periodic fluctuations in the external activity of animals, the beginning and end of rhythmically repetitive actions are determined by the rhythm of the “internal clock” synchronized with space time. Significant corrections or changes are made to behavioral rhythms by various biologically important environmental factors, but the overall “outline” of instinctive behavior is determined by self-excited oscillatory processes with a period of approximately 24 hours (circadian, circadian) rhythm.

Under normal conditions, this rhythm is synchronized with changes in the environment, determined by the rotation of the Earth around its axis during the day. However, even in artificial conditions of complete isolation of an animal, it is possible to observe the usual change of forms of activity in the same terms as in normal conditions. This may be, for example, changes associated with the change of day and night, although the animal is in the experiment in conditions of constant uniform illumination.

In addition to circadian rhythms, shorter rhythms, repeated many times during the day, also appear in the behavior of animals. Thus, the German ethologist V. Schleidt established that the turkey’s clump is quite regularly repeated periodically, even in the case when the bird is completely isolated from the outside world and even hearing-impaired. Of course, in normal conditions, the flow of internal rhythms changes under the influence of external influences (auditory, visual and other stimuli, meteorological factors, etc.), and also depends on the general physiological state of the animal.

The “internal clock” is also necessary for the orientation of animals in space. A good example of this is the orientation of the birds during the flight. Guided, for example, by such an astronomical reference point as the sun, birds should take into account its position in the sky at any given time of day, which happens by comparing the perceived information about the position of the sun with the phases of the circadian rhythm.

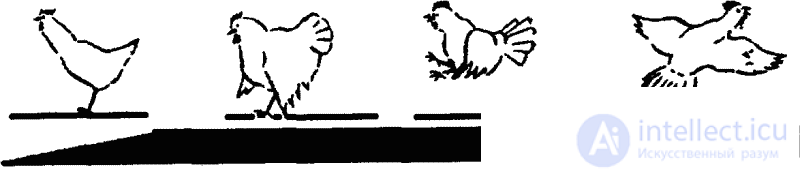

The already mentioned experiment of Schleidt shows that endogenous processes in the nervous system are capable of determining the fulfillment of certain instinctive movements and in the complete absence of adequate external stimuli. Thus, the German neurophysiologist E. Holst discovered a number of zones in the brainstem of the chicken's brain stem, the activation of which (in the experiment with electric current) causes typical instinctive movements of various functional significance. At the same time, it turned out that when one and the same part of the brain was irritated, with an increase in the power of the stimulation, one instinctive action was replaced by another in a natural sequence. The result was a chain of types of typical movements performed by the hen in a certain biologically significant situation, for example, at the sight of a land enemy approaching it. At the same time, not only the performance of motor reactions, but also the sequence of their appearance corresponded in the same way to the natural behavior of the chicken: at first, only slight anxiety, then rise, heightened anxiety, and finally, take-off (Fig. 6). Considering that all this happened in the absence of any adequate external stimuli, it becomes clear that not only individual instinctive movements can be performed on a purely endogenous basis, but also whole systems of such movements — instinctive actions. Of course, under natural conditions such systems of type-like, innate actions are activated by the influence of external, exogenous agents, in our example, by the actual approximation of an enemy perceived by exteroceptors. In this case, its gradual approximation will cause an increase in irritation of the corresponding parts of the brain structures, which was experimentally achieved artificially with the aid of electric shock effects.

Thus, the behavior is basically internally organized in the same way, just based on the systems of biological self-regulation, also encoded in the genetic fund of the species, as well as the processes that determine other functions of the organism. This is the manifestation of the unity of all forms of animal activity.

External factors of instinctive behavior

When they talk about the autonomy of internal factors of behavior, about their independence from the external environment, it must be remembered that this independence is only relative. Already from Holst’s experiments, it can be seen that endogenous activity does not exist either “by itself” or “by itself”: the significance of these spontaneous processes in the central nervous system is to prevent the emergence of vital situations (“if anything happens, everything is ready "). As a result, the animal is capable of responding to the change in the environment immediately and with the maximum benefit for the first signal.

This readiness is ensured by the fact that the corresponding endogenous systems are periodically activated both by their own rhythm and by external influences (for example, by changing the length of daylight, by increasing or decreasing the temperature, etc.). However, instinctive movements, according to the ethological concept, are blocked by a special system of “innate trigger mechanisms”. The latter are a set of neurosensory systems that ensure that behavioral acts coincide with biologically adequate environmental conditions (the “starting situation”). As soon as the animal finds itself in such a situation, the corresponding innate trigger mechanism recognizes, evaluates and integrates the stimuli specific for a given instinctive reaction, after which the disinhibition occurs, the “blocking” is released. Obviously, at the same time, activation of the corresponding nerve centers and a decrease in the thresholds of their irritability occur.

A characteristic feature of innate triggers is the selectivity of response to external stimuli: they respond only to completely specific combinations of stimuli, which can only cause a biologically expedient response. In other words, in the sensory sphere there is a certain “filtering” function, expressed in a specific pre-adaptive “readiness” to perceive such stimuli.

So, thanks to innate triggers, the intrinsic motivation of behavior gets “going outside”, i.e., it creates the possibility, without individual experience in biologically significant situations, to react in such a way that it contributes to the preservation of the individual and the species.

Summarizing the above, we can say that a congenital trigger should be understood as a set of neurosensory systems that ensure the adequacy of behavioral acts in relation to the “starting situation”: tuning the analyzers to the perception of specific stimuli and recognizing the latter, integrating the corresponding stimuli and disinhibition (or activation) of the nervous centers associated with this behavioral act.

External stimuli, which in their entirety constitute a triggering situation, are called “key stimuli”, since they approach their innate triggers as the key to the lock. Key stimuli are such signs of environmental components to which animals react, regardless of their individual experience, with innate, type-typical behaviors, more precisely, with certain instinctive movements. In the described behavior of the chicken, these will be certain common features characteristic of all its land enemies.

In addition to the actually disinhibiting key stimuli (also called “trigger stimuli”), there are also tuning key stimuli that preliminarily lower the irritability threshold of the nerve centers involved in the animal’s actions, as well as directing the key stimuli discussed in discussing taxis. A common property of all key stimuli is that they are specific elementary signs of vital components of the environment. Ключевыми раздражителями являются простые физические или химические признаки («просто» форма, размер, подвижность, цвет, запах и т. д.), или их пространственные отношения (взаиморасположение деталей, относительная величина и т. д.), или же векторы. Носителями этих признаков могут быть как другие животные, так и растения и объекты неживой природы. В последнем случае ключевые раздражители выполняют преимущественно направляющую функцию. Так, например, немецкий этолог Ф. Вальтер показал, что у детенышей антилоп ключевым стимулом, определяющим выбор места отдыха (лежа, неподвижно), является «что-то вертикальное» вне зависимости от того, что конкретно это за объект.

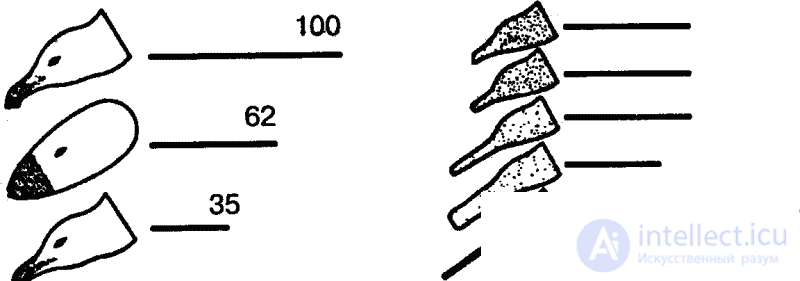

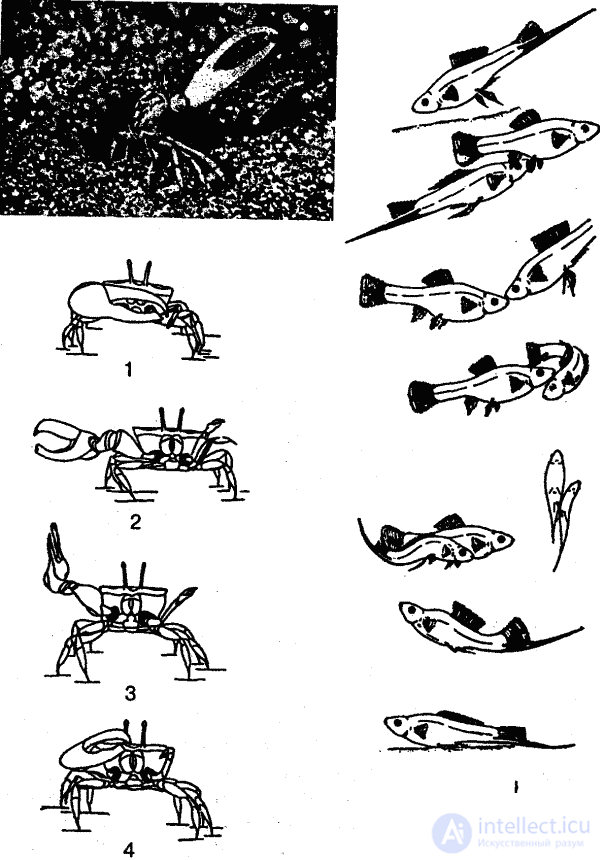

Наилучшим образом изучены ключевые раздражители, носителями которых являются животные. Эти раздражители представляют особый интерес и потому, что являются первичными, генетически фиксированными элементами общения у животных. Так, в ставших уже классическими опытах голландского зоолога Н. Тинбергена, одного из основоположников современной этологии, с помощью макетов изучалась пищевая реакция («попрошайничество») птенцов серебристых чаек (клевание клюва родительской особи) и дроздов (вытягивание шеи и раскрытие клюва) при появлении родительской особи.

В естественных условиях голодный птенец серебристой чайки клюет красное пятно на желтом клюве родителя, и тот в ответ отрыгивает пищу в рот птенцу. В опытах предъявлялась серия все более упрощаемых моделей — макетов. Первая модель точно воспроизводила внешний облик естественного носителя ключевых раздражителей, т. е. головы взрослой серебристой чайки с желтым клювом и красным пятном на нем. В последующих моделях путем проб постепенно исключались отдельные детали, и в результате макет становился все менее похожим на голову птицы (рис. 7). В конце концов остался лишь плоский красный предмет с продолговатым выступом. Но этот предмет оказался способным вызвать даже более сильную реакцию птенцов, чем исходная модель. Еще более эта реакция может быть усилена, если этот макет заменить тонкой белой палочкой, исчерченной поперечными темно-красными полосами. Ключевыми раздражителями в данном примере будут просто «красное» и «продолговатое».

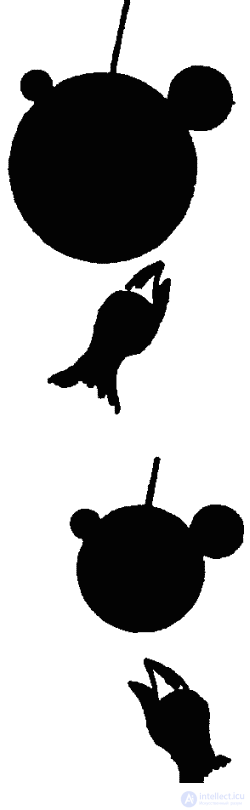

В опытах, проведенных Тинбергеном с десятидневными птенцами дроздов, выявилась другая категория ключевых раздражителей — взаиморасположение и относительная величина деталей объекта-носителя. В качестве макетов использовались плоские диски. Если показать птенцам такой круг, они будут тянуться к его верхней части (местонахождению головы птиц). Если же к большому кругу прибавить маленький, птенцы потянутся к нему. Если, наконец, прибавить к большому кругу два меньших круга, но разных размеров, то решающее значение приобретет относительная величина этих фигур. Размеры «головы» не должны приближаться к размерам «туловища»: при большом «туловище» птенцы потянутся к большему дополнительному кругу («голове») (рис. 8), при маленьком же—к меньшему.

Интересные опыты проводил еще в середине 30-х годов Г. Л. Скребицкий совместно с Т. И. Бибиковой на подмосковном озере Киёво, изучая отношение чайки к ее яйцам. Яйца перекладывались из гнезда в гнездо, заменялись яйцами других видов, искусственными яйцами, а затем и различными посторонними предметами различной величины, формы и окраски. Оказалось, что чайки садились как на чужие, так и на деревянные, стеклянные, каменные, глиняные яйца различной величины и самой разнообразной окраски и начинали их «высиживать». То же самое наблюдалось, когда вместо яиц в гнездо подкладывались разноцветные шары, камешки или картофелины. По свидетельству экспериментаторов, «чайки, сидящие на таких предметах, представляли очень оригинальную картину, но в особенности необычайным становилось зрелище, когда согнанная с гнезда птица возвращалась к нему обратно и, прежде чем сесть, заботливо поправляла клювом разноцветные шары, камешки или картошку». [35]

Если, однако, чайкам подкладывались предметы иной формы, например кубики или камни с неровными краями, поведение птиц заметно изменялось. Когда за край гнезда клалось по одному яйцу и инородному предмету, птицы вкатывали обратно в гнездо наряду с яйцами лишь округлые гладкие предметы, размеры которых соответствовали размерам яиц. В известных пределах не препятствовали этому существенные отклонения от нормы в весе (каменное яйцо весило в два с лишним раза больше, чем чаечье), материал, из которого был изготовлен предмет, и окраска.

Исследователи пришли к выводу, что положительная реакция чайки на яйцо определяется лишь несколькими его элементарными признаками: округлостью, отсутствием выступов, углублений или насечек (рис. 9). Именно эти признаки и выступали здесь как ключевые раздражители.

Важная особенность действия ключевых раздражителей заключается в том, что они подчиняются закону суммации: с увеличением их параметров пропорционально усиливается инстинктивная реакция животного. В экспериментальных условиях это может привести к так называемым «супероптимальным» реакциям, когда животное «преувеличенно», сильнее, чем в норме, реагирует на искусственный раздражитель, в котором «сгущены краски». Мы уже встречались с этим явлением при описании опыта с птенцами чайки, когда они сильнее реагировали на поперечно исчерченную красными полосками палочку, чем на настоящий клюв живой птицы. Суммация проистекает здесь из многократности красных меток и их большей контрастности.

Эффект супероптимальной реакции может в условиях эксперимента привести даже к биологически абсурдному поведению животного. Если, например, предложить чайке два яйца разной величины, она закатит в гнездо более крупное. В итоге может возникнуть такое положение, что птица бросит свое яйцо, чтобы попытаться высиживать деревянный макет яйца гигантских размеров, обладающих супероптимальными признаками ключевого раздражителя.

Как видно из приведенных примеров, ключевые стимулы действуют на поведение животного принудительно, заставляя его выполнять определенные инстинктивные движения, невзирая на возможно воспринимаемую животным общую ситуацию. Это объясняет многие, ранее казавшиеся загадочными моменты в поведении животных.

Так, например, еще в начале нашего века один из авторов антропоморфических сочинений по психологии животных Т. Целл дал следующий ответ на вопрос о том, почему крупные хищники в нормальных условиях при встрече с человеком не нападают на него: например, лев не нападает не потому, что почитает человека, а потому, что не уверен в исходе схватки. «Есть ли у человека оружие, да какое оно, это оружие? — думает лев. — Да ну его, пойду-ка я лучше своей дорогой».

Конечно, лев, как и другие крупные хищники, как правило, уклоняется от нападения на человека не потому, что руководствуется такими глубокомысленными рассуждениями. Разгадка «почтительного» отношения диких зверей к человеку, очевидно, кроется в следующем. Будучи сытым, хищник не реагирует и на присутствие животных, которыми обычно питается. У голодного же хищника преследование животных-жертв и нападение на них обусловливаются сочетанием рассмотренных выше внутренних факторов (первопричина — изменение уравновешенности внутренней среды организма в результате недостатка питательных веществ) с соответствующими внешними стимулами — ключевыми раздражителями, носителями которых являются естественные объекты питания, т. е. животные-жертвы, но не человек.

Даже самый кровожадный хищник не волен нападать на кого угодно и когда угодно. Эти действия также ориентируются во времени и пространстве ключевыми раздражителями, как и все прочие поведенческие акты. Другими словами, дело не в том, «хочет» или «не хочет» животное поступить так или иначе. Если внутреннее состояние животного соответствует определенной внешней пусковой ситуации, то оно волей-неволей вынуждено вести себя так, как это диктует для данных условий генетически зафиксированный код видотипичного поведения.

So, in the process of evolution, adaptations arise to the more permanent components of the external environment, which are necessary to satisfy the needs that constantly arise as a result of changes in the internal environment of the organism. Finding (or avoiding) components of the environment that are important for the body is carried out by targeting the typical stimuli according to the typical features of these components.

Результаты этой ориентации реализуются нейросенсорными системами (врожденными пусковыми механизмами), которые действуют рефлекторно и включают эндогенные, генетически фиксированные компоненты инстинктивного поведения. Таким образом, действуя «вовне», врожденные пусковые механизмы обеспечивают избирательную направленность внешней активности организма лишь на определенные сигнальные стимулы; действуя же «вовнутрь», они осуществляют оценку и отбор поступающей через рецепторы информации и ее реализацию для активации или понижения порогов раздражимости соответствующих нервных структур, для снятия «блокировки», растормаживания эндогенных нервных процессов, мотивирующих инстинктивные движения и действия. Таким образом осуществляется на врожденной основе корреляция внутренних потребностей организма с биологически существенными изменениями в окружающей его среде.

Only in this correlation is the entire biological significance of endogenous motivation of behavior. Internal stimuli serve only to effect movement in relation to the environment, without which the organism — precisely as a self-regulating system — is not viable. And in this broad sense, the activity of the entire nervous system as a whole is always reflexive.

Equally, even the most apparently “far hidden” from the external environment behavioral factors themselves depend on metabolic processes. These processes are directly related to the surrounding environment. And since the body actively regulates, creates the necessary external prerequisites for the normal course of metabolic processes just by means of behavior, the circle closes. And in this respect, the independence of endogenous automatisms, spontaneous activity of the nervous system, and the ability to “self-program” manifest themselves. It is clear that all these endogenous processes are only independent of the external environment, since they are only indirectly related to it.

Structure of instinctive behavior

Search and final phases of the behavioral act

It was said above that the key stimuli act forcibly, that the animal is forced in its behavior to completely obey the starting situation. But does this mean that animals have no opportunity to show their own initiative, to make some independent choice? Far from it!

The initiative, selective attitude of the animal to the environment is manifested primarily in the active search for the necessary starting situations and in the selection of the most effective possibilities for carrying out behavioral acts. It must be emphasized that it is a question of finding exactly the stimuli emanating from biologically significant objects, and not the objects themselves. We now know that these are key stimuli with a guide or trigger function.

Even more than half a century ago, the American animal behavior researcher W. Craig showed that instinctive actions consist of separate phases. First of all, Craig singled out two phases, which in the ethological literature are called “search” (or “preparatory”) and “final”. During the search phase, the animal finds (hence the name of the phase) those key stimuli, more precisely, their combinations (i.e. starting situations), which will eventually lead to the final phase, which embodies the biological significance of the whole instinctive action.

All intermediate stimuli do not constitute an end in itself for the animal and are valuable only insofar as they lead to the perception of key stimuli of the final behavior. Only in the final phase does the animal actually consume the vital elements of its environment. But the search for adequate stimuli is for animals the same vital necessity as the consumption of elements of the environment.

The search phase is always divided into several phases; however, in the final phase, such divisions are not detected at all, or it consists of only a few strictly sequentially performed movements.

Craig built his concept on the data he received as a result of studying the eating behavior of animals. Let us give an example of this sphere of behavior. A predator going on a hunt does not know at first where its possible prey is located, therefore its first movements have the character of a non-directional search. As a result, it sooner or later falls within the scope of the stimulus emanating from the animal-victim. The first key stimulus was discovered, which includes the next stage - directional orientation for additional stimuli, clarification of the location of the victim animal. Then follows sneaking (or chasing), sketching (jumping) and mastering the prey, killing it, sometimes dragging carcasses to another place, breaking up into separate pieces, and finally grabbing pieces of meat with their teeth and swallowing them. In this chain of successively performed actions and movements, only the last two links (the actual act of eating) refer to the final phase of the described predatory food-producing behavior, all the other steps together constitute search (or preparatory) behavior. True, within each such stage there are preparatory and final phases, with which each stage ends. In this case, sometimes there are several degrees of subordination (like the "nested doll"), so that in general there is a very complex structure of activity.

The situation is similar in other, it would seem, much simpler spheres of behavior, such as rest and sleep. The animal first looks for a place to rest or spend the night (trees, shelters, indentations in the soil or just certain areas of open space), then arranges (improves) the place found (digs, crushes vegetation), sometimes even cleans, and only after that does it fit way!). Only laying is the final phase, the previous stages - the search.

To these examples one could add many more from any sphere of behavior. However, already in the above we can see the following deep differences between the two phases, which determine their essence.

Search behavior is the plastic phase of instinctive behavior. It is characterized by a pronounced orientational-exploratory activity of animals and the interweaving of congenital and acquired components of behavior based on individual experience. Everything related to the plasticity of instincts, in particular with modifications of instinctive behavior, relates to search behavior.

The final behavior, on the contrary, is a rigid phase. The movements performed in it are distinguished by strict sequence, stereotype, and are predetermined by the corresponding macro- and micromorphological structures. Acquired components play an insignificant role here or even are absent. Therefore, variability is limited by individual (genetically fixed) variability. This includes everything that was said about the constancy, rigidity of instinctive behavior and the coerciveness of the action of key stimuli. Here, almost everything is innate, genetically fixed. As for the movements performed in the final phase, this is actually instinctive movements, or “innate motor coordination,” so named by the Austrian scientist C. Lorenz, one of the founders of modern ethology.

Instinctive movements and taxis

The general characteristic of instinctive movements has already been given above. It was also said that they are the “custodians” of the most valuable, vital that the species has accumulated as a result of natural selection, and that this is what determines their independence from random environmental conditions. The fox, which produces the instinctive movements of burying meat on the stone floor, behaves "meaninglessly." But the phylogenesis of foxes did not take place on the stone substrate, and it would be fatal for the further existence of the species if, due to the occasional, temporary residence of an individual in such completely unusual conditions for foxes, the behavior so useful for these animals would disappear. So it is better to make a burial movement under any circumstances, and a “tough” innate behavior program causes the animal to do it.

The general orientation of instinctive movements is carried out by taxis, which, according to Lorentz, are always intertwined with innate motor coordination and together with them form a single instinctive reaction (or chains of several such reactions).

Like instinctive movements, taxis are congenital, genetically fixed reactions to certain agents of the environment. But if instinctive movements arise in response to starting stimuli, then taxis respond to keying stimuli that are incapable of determining the beginning (or end) of any instinctive reaction, but only change the vector of its course.

Thus, taxis provide spatial orientation of the motor activity of animals towards favorable or vital environmental conditions (positive taxis) or, conversely, from biologically low-value or dangerous conditions (negative taxis). In plants, similar reactions are expressed in changes in the direction of growth (tropism).

By the nature of the orienting external stimuli, taxis are divided into photo, chemo, thermo, geo, radio, anemone, hydrotaxis (reactions to light, chemical stimuli, temperature gradients, gravity, flow of air, air flow, humidity of the environment) etc. At different levels of evolutionary development, taxis have varying degrees of complexity and perform different functions, which will be discussed later in the review of the evolution of the psyche. Now it is important to emphasize that taxis are permanent components of even complex forms of behavior, with the higher forms of taxis acting in close combination with the individual experience of the animal.

We have already met with guiding key stimuli when the orientation of chicks according to relative optical stimuli was described. The very appearance of an object (in the experiment — a disk, in natural conditions — the parent individual) is the starting stimulus of the “begging” reaction, the interposition of details of this object is the guiding key stimulus of this reaction, and the spatial orientation of the chicks according to this irritant is positive phototaxis.

In the same way, the red color itself is for the chick of a silvery gull, a triggering key irritant, which determines its food reaction (along with another triggering irritant — the appearance of a bird, more precisely, its head with a beak). The location of the red spot on the beak directs the reaction of the chick in a biologically beneficial way based on positive phototaxis and thus serves as a guiding key stimulus.

In the 1930s, Lorenz and Tinbergen jointly studied the relationship between congenital motor coordination and taxis, using the example of the reaction of eggs to the nest of a gray goose. The view of an egg-like object (something round, without projections, etc.) located outside the nest serves in this bird as a key stimulus for the racking-in reaction as in the seagull sitting on the nest in the described experiments of Skrebitsky. The corresponding congenital motor coordination is the repetitive movement of the beak to the bird's chest, which will stop only when the object touches the bird sitting in the nest.

If we put a cylinder perpendicular to the beak in front of the edge of the nest (geese reacted positively to such an object), then all instances of the bird’s behavior would be limited to such instinctive movements. If we put an egg or its layout, then additional head movements from side to side appear, giving the movement of the object the right direction to the nest. Indeed, unlike the cylinder, the egg will roll back to the left, then to the right. The appearance of these deviations serves as a guiding irritant for taxis lateral movements of the head. So, taxis can orient in higher animals the instinctive movements not only of the whole organism, but also of separate parts of the body and organs.

Instinctive movements and taxis form the final phase of each behavioral act. At the same time, they enter as component parts into the search phase, which, as already mentioned, serves to search for external trigger situations that allow the body to reach the final phase of this act. The search phase is characterized by large lability and a very complex structure. Instinctive movements complete each intermediate stage of this phase, with the result that the end of each such stage also acquires the features of the final behavior. Taxis are supplemented in the search phase with orientation-research reactions that continuously provide the body with information on the state, parameters and changes of environmental components, which allows it to evaluate the latter within the framework of a general search behavior.

Acquired components of an instinctive act

Along with those indicated in the search phase of any instinctive act, they are always contained - in varying degrees and in different combinations - and all elements of behavior that relate to learning, not excluding higher forms of behavior, of the intellectual type. That is why we believe that talking about instinctive actions (but not movements!) Means talking about behavioral acts in general.

In fact, all that animals can learn is directed only to one thing — to the earliest and most economical achievement of the final behavior. There is nothing in the behavior of animals that would not be completed by this final phase — instinctive movements or related reactions, i.e., innate motor coordination. And this clearly shows the unity of instinctive behavior and learning.

Of course, this does not apply equally to all phases of the search phase. The fact is that the lability of behavior is not the same at different stages of this phase and decreases more and more as it approaches the final phase.

The transition from one stage of search behavior to another means the active search and finding of key stimuli by animals, changing one stage of search behavior to another in a strictly regular sequence. This is accompanied by a stepwise narrowing of the animal's activity: its behavior is increasingly determined by combinations of stimuli specific for this behavioral act, it becomes more and more directed towards the final, final instinctive movements, the possibilities of individual modification of the animal's behavior are narrowed, until the final starting situation reduces these possibilities to to zero.

So, for example, the swallow, starting to build a nest, should, first of all, find a place where it is possible to collect nest-building material. The initial non-directional inspection of the area is the first stage of nesting activity. The speed of the passage of this extremely labile stage depends, first of all, on the individually variable components of behavior, primarily on the already existing individual experience. Depending on their individual psychic abilities, each bird solves this problem in its own way, more or less efficiently.

The next stage of the search phase is the search and collection of nesting material at the found suitable place. Here, the possibilities for individual change of type-typical behavior are already narrowed, but nevertheless individual skill continues to play an important role. The amplitude of possible individual deviations based on previous experience at the third stage of search behavior — transportation of nest building material to the nest building site — is even smaller. Here only some, not very significant variations in the speed and trajectory of the flight are possible. Otherwise, the behavior of all the swallows is already very stereotypical.

And finally, the final phase - the attachment of particles to the substrate - is already done with completely stereotypical instinctive movements. Here, only a genetically determined individual variability of type-typical behavior gives us the known differences in the structure of individual nests.

Thus, the “freedom of action” of an animal gradually decreases, the amplitude of its behavior variability decreases as it approaches the final phase in accordance with the increasingly limited and specific environmental conditions, combinations of stimuli involved in this behavior.

The farther from the final phase and the greater the amplitude of variability of type-typical behavior, the more opportunities there are to include elements of learning, individual experience, and the greater the proportion of these elements. Thus, individual experience is realized primarily in the initial stages of the search command. And one more thing: the higher the mental development, the more significant are the adjustments made to rigid type-typical behavior, but again mainly at the initial stages of the search phase. All this applies, of course, to search and final behavior within each stage of search behavior.

The complexity and diversity of the structure of instinctive behavior

The two-phase structure of instinctive actions is given here only in the form of a very complete, simplified general scheme. In reality, various complications and modifications often occur. First of all, it must be borne in mind that the search phase can also occur under a negative sign - in the form of evasion and avoidance of certain agents of the environment. Further, it is possible to reduce search behavior, the loss of its individual stages, or even inversion. Sometimes the final movement occurs so quickly that the search phase does not have time to fully manifest itself. In other cases, the search behavior can be turned off from its channel and lead to "alien" final behavior.

Search behavior can take the form of the final behavior and exist along with the true final phase. In this case, outwardly identical actions will have a twofold qualitatively different motivation.

Of great interest are the various cases of incomplete occurrence of an instinctive act, when the actions of the animal do not reach the final phase. In animals with the most highly developed psyche, the intermediate stages of search behavior, i.e., the search for stimuli per se, can in this case - as an exception - become an end in themselves of their behavior. Here we meet with the instinctive basis of the most complex forms of exploratory behavior that form the foundation of animal intelligence.

Already this list shows the diversity of instinctive actions; Let us add also that almost never at the same time only a single instinctive act takes place, but there is a complex interaction between several simultaneous actions.

Instinctive behavior and communication

All animals periodically enter into intraspecific contacts with each other. First of all, this refers to the field of reproduction, where there is often more or less close contact between sexual partners. In addition, representatives of the same species often accumulate in places with favorable conditions of existence (abundance of food, optimal physical parameters of the environment, etc.). In these and similar cases, biological interaction between animal organisms occurs, on the basis of which the phenomena of communication originated in the process of evolution. Neither any contact between male and female, much less the accumulation of animals in favorable places (often with the formation of a colony) is not a manifestation of communication. Последнее, как и связанное с ним групповое поведение, предполагает как непременное условие не только физическое или биологическое, но прежде всего психическое взаимодействие (обмен информацией) между особями, выражающееся в согласовании, интегрировании их действий. Как еще будет показано, это относится к животным, стоящим выше кольчатых червей и низших моллюсков.

Дополняя сказанное, необходимо подчеркнуть, что об общении можно говорить лишь тогда, когда существуют особые формы поведения, специальной функцией которых является передача информации от одной особи к другой. Другими словами, общение, в научном значении этого термина, появляется лишь тогда, когда некоторые действия животного приобретают сигнальное значение. Немецкий этолог Г. Темброк, посвятивший много усилии изучению процессов общения и их эволюции, подчеркивает, что о явлениях общения и соответственно подлинных сообществах животных (стадах, стаях, семьях и т. д.) можно говорить лишь тогда, когда имеет место совместная жизнь, при которой несколько самостоятельных особей осуществляют вместе (во времени и пространстве) однородные формы поведения в более чем одной функциональной сфере. Условия такой совместной деятельности могут меняться, иногда она осуществляется при разделении функций между особями.

Добавим еще, что если общение отсутствует у низших беспозвоночных и только в зачаточных формах появляется у некоторых их высших представителей, то, наоборот, оно присуще всем высшим животным (включая и высших беспозвоночных), и можно сказать, что в той или иной степени поведение высших животных в целом осуществляется всегда в условиях общения (хотя бы периодического).

Как уже упоминалось, важнейшим элементом общения является обмен информацией — коммуникация. При этом информативное содержание коммуникативных действий (зоосемантика) может служить опознаванию (принадлежности особи к определенному виду, сообществу, полу и т. п.), сигнализировать о физиологическом состоянии животного (голоде, половом возбуждении и пр.) или же служить оповещению других особей об опасности, нахождении корма, места отдыха и т. д. По механизму действия (зоопрагматика) формы общения различаются каналами передачи информации (оптические, акустические, химические, тактильные и др.), но во всех случаях коммуникации животных представляют собой (в отличие от человека) закрытую систему, т. е. слагаются из ограниченного числа видотипичных сигналов, посылаемых «животным-экспедиентом» и адекватно воспринимаемых «животным-перцепиентом».

Общение между животными невозможно без генетической фиксации способности как к адекватному восприятию (что обеспечивается таксисами), так и к передаче «кодированной» информации (что обеспечивается врожденными пусковыми механизмами). Наследственно закрепленные, инстинктивные действия, с помощью которых выполняется передача информации, могут приобретать самостоятельное значение. Здесь действуют те же закономерности, что и при других формах инстинктивного поведения, но носителями ключевых раздражителей являются в данном случае сородичи или животные других видов.

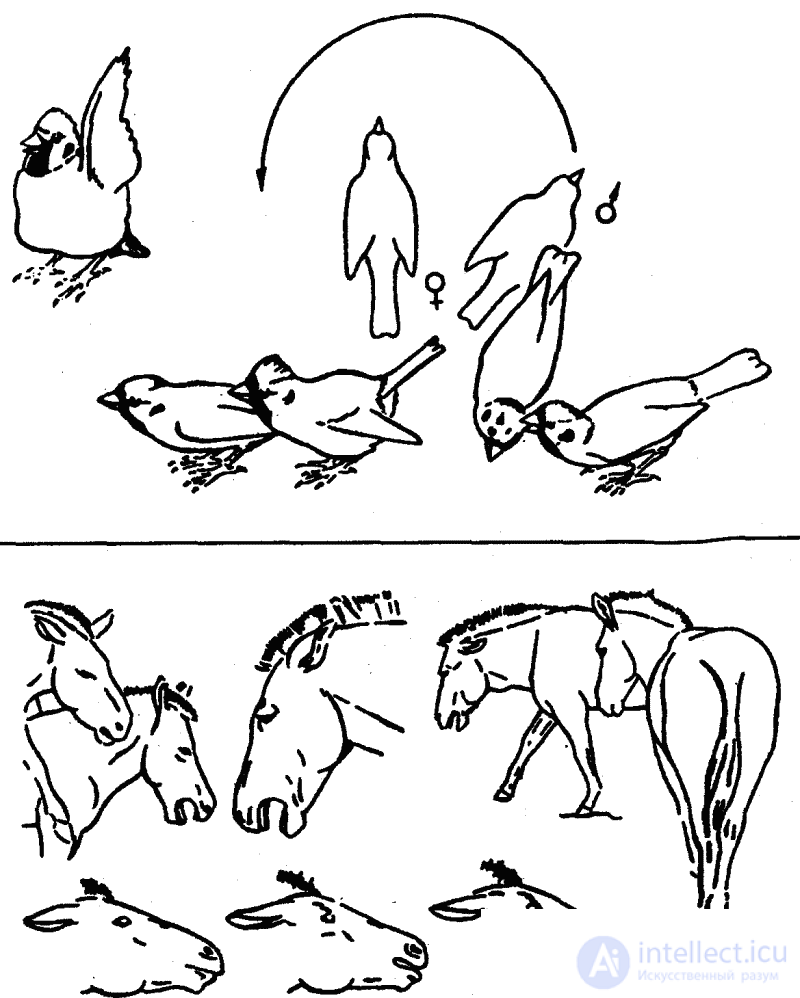

Среди оптических форм общения важное место занимают выразительные позы и телодвижения, которые состоят в том, что животные весьма заметным образом показывают друг другу определенные части своего тела, зачастую несущие специфические сигнальные признаки (яркие узоры, придатки и т. п. структурные образования). Такая форма сигнализации получила название «демонстрационное поведение». В иных случаях сигнальную функцию выполняют особые движения (всего тела или отдельных его частей) без специального показа особых структурных образований, в других — максимальное увеличение объема или поверхности тела или хотя бы некоторых его участков (посредством его раздувания, расправления складок, взъерошивания перьев или волос и т. п.). Все эти движения всегда выполняются «подчеркнуто», нередко с «преувеличенной» интенсивностью (рис. 10). Но, как правило, у высших животных все движения имеют какое-то сигнальное значение, если они выполняются присутствии другой особи.

Наиболее полноценная, четкая передача информации достигается, однако, тогда, когда появляются специальные двигательные элементы, выделившиеся из «обычных», «утилитарных» форм поведения, утративших в ходе эволюции свою первичную «рабочую», «механическую» функцию и приобретшие чисто сигнальное значение.

Первичные движения получили в этологии название «автохтонных» движений; вторичные, приобретшие новую, в данном случае сигнальную, функцию, — «аллохтонных». В таком случае сам рисунок стереотипно, у всех представителей данного вида одинаково выполняемого движения является условным выражением определенной биологической ситуации (биологически значимого изменения в среде или внутреннего состояния животного). Такие видотипичные стереотипные движения с четкой информативной функцией получили в этологии название «ритуализованных движений». Ритуализация характеризуется условностью выполняемых действий, которые служат лишь для передачи определенного, причем совершенно конкретного информативного содержания. Эти действия генетически жестко фиксированы, выполняются с максимальной стереотипностью, т. е., по существу, одинаково всеми особями данного вида, и поэтому относятся к типичным инстинктивным движениям. По этой причине все животные данного вида и в состоянии «правильно» понимать значение подобных оптических (или акустических) сигналов общения. Это типичный пример максимальной ригидности, консерватизма в поведении животных.

Ритуализованные движения выполняются в строгой последовательности в форме более или менее сложных видотипичных «церемониалов» или «ритуалов», причем, как правило, в виде «диалога» двух животных. Чаще всего они встречаются в сферах размножения (брачные игры) и борьбы («мнимая борьба») и отображают внутреннее состояние особи и ее физические и психические качества. Наряду с врожденными существуют и благоприобретаемые формы общения, о которых пойдет речь позже.

Все формы общения играют существенную роль в жизни высших беспозвоночных и позвоночных, обеспечивая согласованность действий особей. Без коммуникации с помощью различных химических, оптических, акустических, тактильных и других сигналов у этих животных невозможно даже сближение и контактирование самцов и самок, а, следовательно, и продолжение рода. Особое значение приобретает общение особей одного, реже разных видов в условиях их совместной, групповой жизни как основа группового поведения.

Как уже говорилось, групповое поведение появляется (по меньшей мере в развитых формах) вместе с общением только у высших беспозвоночных и выражается в согласованных совместных действиях животных, живущих в сообществах. В отличие от скоплений животных, возникающих в результате идентичной положительной реакции на благоприятные внешние условия, сообщества характеризуются относительно постоянным составом его членов и определенной внутренней структурой, регулирующей отношения между ними. Эта структура нередко принимает форму иерархических систем соподчинения всех членов сообщества друг другу, чем обеспечивается сплоченность последнего и его эффективное функционирование как единого целого. Не меньшее значение имеет в этом отношении выделение вожаков, или «лидеров», регулирование отношений между молодыми и старыми животными, совершенствование ухода за потомством и т. д.

Психический компонент инстинктивного поведения

Психический компонент инстинктивного поведения, точнее, психическое отражение при инстинктивных действиях животных необходимо изучать на завершающей фазе поведенческого акта и в какой-то степени на непосредственно примыкающем к ней последнем этапе поисковой фазы, поскольку здесь элементы научения играют наименьшую роль. При этом надо сказать, что в свете современных данных и концепций этологии этот вопрос еще специально не изучался и поэтому приходится здесь ограничиваться лишь некоторыми общими соображениями.

Мы видели, что по мере приближения к завершающей фазе движения животного становятся все более ограниченными, однообразными, стереотипными, и есть все основания полагать, что в такой же мере отражение окружающего мира становится все более бедным, ограниченным. Если на первых этапах поискового поведения животное в поиске ключевых раздражителей руководствуется многими разнообразными ориентирами в окружающей среде, то по мере сужения действия внешних агентов, направляющих поведение животного, ориентация все больше осуществляется только по направляющим ключевым раздражителям, а в завершающей фазе производится уже исключительно по ним.

Вместе с тем мы теперь уже знаем, что как направляющие, так тем более и пусковые ключевые раздражители представляют собой элементарные физические и химические признаки, воспринимаемые животным «в отрыве» от объекта, которому они присущи. Следовательно, животное получает на завершающей фазе лишь весьма неполную, «однобокую» информацию о некоторых — причем несущественных — внешних признаках объектов инстинктивных действий. Правда, эти признаки являются постоянными и в этом отношении характерными для этих объектов.

Однако, что для нас сейчас важно, животное, реагируя на эти признаки, в сущности, не получает сведений о самом объекте (неодушевленном предмете или другом живом существе): признаки — ключевые раздражители — являются только ориентирами, направляющими действия животного на этот объект, носитель этих ориентиров.

Это с совершенной очевидностью вытекает из приведенных выше экспериментов, в которых подлинные объекты инстинктивных действий заменялись весьма абстрактными макетами. Вспомним, что в этих условиях удалось получить даже сверхоптимальные «преувеличенные» инстинктивные реакции. Самец колюшки в завершающей фазе борьбы за гнездовой участок не видит разницы между живой рыбой-соперником и куском жести или пластмассы. Он видит только «красное», и этого ему в данной ситуации вполне достаточно, чтобы среагировать на это «красное», которое в данном случае, кстати, выступает одновременно как направляющий и пусковой ключевой раздражитель.

Следовательно, здесь налицо первично генерализованная реакция на общий элементарный признак (точнее, на совокупность нескольких таких признаков, поскольку в природных условиях действуют не одно только «красное», но и некоторые другие ключевые раздражители). Этот признак воспринимается недифференцированно, как простое ощущение (точнее, воспринимаются суммы ощущений). Об этом свидетельствует отсутствие реакций на форму объекта — носителя признака, да и вообще на объект (предмет или рыбу) как таковой. Ясно, что здесь обнаруживается очень бедное, крайне поверхностное и ограниченное отражение окружающего мира, низшая форма психического отражения. Неинтересно, что такое отражение, свойственное низшим представителям животного мира, в полной мере сохранилось и у высших животных — позвоночных и продолжает у них играть главную роль в поддержании жизнедеятельности особи и продолжении рода.

О том, как это понимать, уже говорилось выше. Эволюция животной жизни могла идти только по пути отбора как можно более простых, но и наиболее постоянных ориентиров (или, что не меняет существа дела, создания таких специфических ориентиров, когда речь идет о животных одного вида, являющихся носителями ключевых признаков), руководствуясь которыми организмы могли бы успешно, не отвлекаясь другими, случайными, изменчивыми признаками, осуществлять наиважнейшие жизненные функции.

Правда, как явствует, например, из описанных опытов с птенцами дроздов, у высших животных ключевые стимулы представлены и более сложными по своей структуре типами. В указанном примере имеет место реакция на конфигурацию и на пространственные соотношения деталей объектов инстинктивных движений, что уже соответствует элементарным восприятиям. Это, очевидно, одно из важных проявлений прогрессивного развития инстинктивного поведения в ходе эволюции. Однако, как показывают те же эксперименты, и здесь нет подлинного предметного восприятия, ибо иначе птенцы не могли бы спутать свою мать с картонным диском.

Примитивность психического отражения на завершающей фазе инстинктивных действий является следствием бедности самой моторики в этой фазе. Как мы знаем, двигательная активность, направленная на окружающую среду, является источником познания этой среды. Однако столь стереотипные движения со столь ограниченной, специальной функцией, какими являются инстинктивные движения, врожденные двигательные координации, не могут служить сколько-нибудь пригодной основой для познания окружающего мира.

Врожденные двигательные координации (во всяком случае в их типичной форме) и не выполняют эту функцию, а ключевые раздражители, воспринимаемые на завершающей фазе (да и на отдельных этапах поискового поведения), не познаются, а узнаются врожденным образом благодаря наличию врожденных пусковых механизмов, чтобы затем использоваться как ориентиры или — и того меньше — как «кнопки» пуска инстинктивных реакций. Здесь больше ничего нет, кроме, вероятно, положительной или отрицательной эмоциональной окраски ощущений от воспринимаемых стимулов и собственных движений.

Познавательные же функции и вообще все богатство психического отражения приурочены к начальным этапам поискового поведения, где в полной мере действуют процессы научения.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology