Lecture

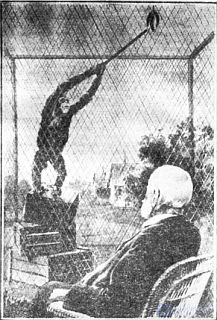

Higher animals, such as apes, can perform quite complex, as if "reasonable" actions, but come to them through "trial and error." In the experiments of I.P.Pavlov, Chimpanzee Raphael learned how to make a pyramid of boxes of different size in order to reach a fruit suspended from the ceiling. At first, this was not possible for Raphael: he put a large box on a small box (and once even put the box on his head), and everything fell. But finally, after many attempts, the correct pyramid began to turn out (Fig. 1). In the experiments of IP Pavlov's pupils, the monkey needed to make a key of several parts, open the locker door with this key and get a treat or a toy. And again the animal had to make many trials, to err many times before it reached the goal.

Such a path passes and the child, getting acquainted with the outside world. Suppose a one and a half year old baby wants to sit on a chair. First, he lies down on his chest, pulls up, pushes the chair, overturns it and falls by itself. Mom picks up and puts the chair, and the baby repeats its attempt, going to the chair on the other side, and again unsuccessfully. Finally, he pushes the wooden box out from under the cubes, gets up on it and climbs into a chair. Just like a monkey, he is looking for those actions that will help achieve the goal, and discards unsuccessful ones.

However, very soon the human child begins to learn from the experiences of adults around him through speech.

Roller 2 years 6 months. He was presented with a clockwork bear who dances. They explain to the boy: “Insert the key into this hole and turn it several times!” - and the child copes with the task without trial and error: for him this method is not necessary at all, since he speaks speech.

With the help of the word, the baby receives from adults and knowledge - at first, very basic, and then more and more profound. He is called objects, tell what they are doing. “Here is a spoon. Hold the spoon so, and now scoop grub! Well done, Mitya, how good is eating porridge with a spoon! ”Says the mother while feeding her one-year-old son.

The child is introduced to certain phenomena. The father explains to the four-year-old Gena where the steam comes from: “Look, the water in the kettle heats up, it becomes steam and rises up. See how much steam is on the window? And the glass is cold, the steam cools down and again becomes water - now droplets have run down the glass! ”A little later, the child’s attention is turned to the cloud:“ The sun warmed the water on the ground, and it became steam, rose up - you remember how from a kettle! - and gathered in a cloud. And when there is a lot of steam there and it cools down, it will rain on the ground. ”

The dependence of the phenomena about which the child learns here can be explained to him so far only with the help of the word - it cannot be seen, touched. That is why speech plays such a huge role in shaping the child’s mental life.

Fig. 1. I.P. Pavlov observes the experience of chimpanzee Rafael.

One of the first importance of speech for the development of the psyche of the child began to study the Soviet psychologist L. S. Vygotsky. Later in our country many psychologists A. A. Lyublinskaya, A. R. Luria, N. Kh. Shvachkin and others devoted this question to many studies. They found that from the early stages of child development (already from the beginning of the second year of life) the word begins to influence the perception of the properties of objects, the formation of ideas about them, etc. The older children are, the stronger and brighter will be the impact of speech on all aspects of their mental activities.

Of utmost importance is the speech in adapting the child to the requirements of human society, establishing contact with other children.

Have you ever observed a difference in the behavior of children who speak well and children with delayed speech development? Here in the younger group of the kindergarten on the carpet in the corner of the room three children play together (they are 3 years and 2 months old). Galya folded two walls at right angles from the cubes and said: “House!” Lena, who was sitting next to her, immediately put a rubber cat in the “house”. "Cat house! Cat house! ”Both girls laughed. Boria, who rode not far away in a wooden rooster, drove him to the house: “Zdlyaste! I came to visit you! ”These children play for a long time and with enthusiasm - they understand each other and can coordinate their actions.

Children who speak speech easily come into contact with adults. The middle group of the kindergarten is going to take a walk, and the teacher helps the children to dress. “Lenya, take the hat out of the locker, put it on, and I will help to tie it up - like this! And where is the scarf, Serezha? Come on, look for him. Well done! ”Children willingly do what the teacher tells them.

In the same group there is Yura - a boy who is very far behind other children in development, speaks poorly and does not understand enough the speech addressed to him. Olya, who was dressing next to her, saw Jura’s bright mittens and extended her hand: “Oh, show me!” - but he did not understand what she wanted, shouted and pushed the girl away; she burst into tears. Such misunderstandings with Yura are very common. Here he went to a group of kids who are building something from cubes. “Add it, too, right here,” one of the boys tells him, but Yura snatches a few cubes from the building: it collapses. The cry, the tears, the fight, and the weight of the matter is that Yura cannot understand other children, cannot get involved in the game and brings only discord and trouble.

Educating children who have delayed speech development presents great difficulties, both in the children's team and in the family. Parents of such children and teachers note that they are stubborn, irritable, cry a lot, they can be difficult to calm. These children are not well included in the general games and activities, because they can not catch their essence and do not understand the requirements. Hence the importance of the fact that the child is timely and fairly well mastered speech.

Understanding the great importance of speech for the entire neuropsychic development of a child, it is natural to inquire about the essence of this phenomenon — then much in the formation of children's speech will become clearer.

Over the past hundred years, scientists of various specialties have done a lot of research to find out the origin and nature of speech. All European languages have been studied, as well as languages of very many backward nations; historical research has been conducted; studied the development of speech in children, its disorders, the activity of the apparatus of speech. Thanks to this, the question of the origin of speech and of what it represents is much clearer. With the most important facts established by scientists, we will meet in this book.

Inherent human ability to speech and verbal thinking have their own background in the development of the animal world.

For a long time it was believed that animals have only more or less complex systems of instinctual (i.e., inborn) sounds, with the help of which contact is established in the herd, flock, etc. Indeed, the cries of animals are mostly involuntary - they are caused by strong excitement: fear, rage, etc. Such screams are also called affective (affect - this is the state of strong excitement). These cries in other animals cause instinctive responses. For example, an alarming cry of a chicken causes a fading reaction even in newly hatched chickens. The cry of fright of rooks recorded on tape, creates panic in the pack of rooks - they are noisy with a rush and fly away. Now they sometimes use such records to drive the birds away from the field they had just planted, where they peck up the seeds.

Affective cries, signals in animals are very diverse. In apes, there are up to thirty shouts of different sound combinations and intonations.

All animals usually exhibit the ability to imitate those sounds that are peculiar to this species. If, for example, one dog barked, then others who are nearby, immediately catch barking; all the cows in the herd begin to moo, if they moaned alone, and so on. The ability to sound imitation of some birds (parrots and birds of the corvidae family) is especially great.

As a means of communication, animals use not only screams, but also movements that are mostly instinctive in nature. Usually these movements are accompanied by screams. Probably, each of us has seen many times and well remembers the pose of an angry dog when it barks at a stranger, or it is strengthened by wagging its tail, bending down its head and jumping, accompanying the whining, with which it meets the owner.

All types of animals have expressive movements of threat, request, fear, etc., to which other animals respond with an instinctive reaction of self-defense, attack, etc.

Observations of the last decades have shown, however, that the means of communication of animals are not limited to instinctive sounds and movements — animals also have forms of communication developed in life experience.

For example, physiologists Yu. Konorsky and S. Miller bent a dog's paw and at the same time gave it food. After some time, being hungry, the dog itself began to bend its paw - requested in this way to eat. N. A. Shustin began to give the dog food when it barked, and gradually the dog learned to ask for food by barking.

In the process of training in animals produced a variety of forms of communication with each other and with people. The possibilities of great apes are especially great in this respect. Many scientists (V. Köhler, R. Yerke, E. Thorndike, M. P. Shtodin, L. G. Voronin, and others) carried out experiments on these animals, so close to humans. Here are some interesting observations made by the Leningrad physiologist A. I. Schastny. When he gave a chimpanzee a triangular token, he fed her, a square one — a water bottle, a round one — offered her a toy. This was repeated many times. Then the monkey was not fed and was given all the tokens at once; she immediately selected a triangular token and handed it to the experimenter. If the monkey was not given a long drink, she chose a square token.

In another experiment, two chimpanzees participated, separated by bars. One monkey was fed and watered, and food was placed near it; the other was hungry, but she was given only a toy; both, in addition, were given sets of tokens. A hungry chimp chose a triangular token (food signal) and thrust it through the grid to the second monkey. A well-fed monkey took this token, gave a banana in exchange, and also thrust a round token. In exchange for a round token, the first monkey would slip a toy while she ate a banana. Thus, it was shown that higher animals can use conditioned signals in communication with other animals and people if they are trained in this.

Under natural conditions, there are also very complex forms of communication between animals, which are produced in their life experiences. Of course, these are only prerequisites for the development of the human form of communication.

In primitive people, gestural and verbal speech arose from affective and sound-imitative screams and accompanying movements. This happened, as scientists believe, under the influence of the fact that people began to use tools. In the process of labor they often had an increasing need to explain something to each other. The use of tools required no longer exclamations, but words-names, and then words-concepts.

In the course of work, another important event occurred: subtle movements of the fingers were improved more and more, and in connection with this, the structure of the brain became more complex. Now this dependence has already been proved (we will dwell on this question in more detail).

Concerning the origin of the words, various assumptions are made. Some scientists believe that speech arose from involuntary shouts (Wow! Fu!, Etc.). Half-jokingly, this theory is called the theory "pah-pah." Indeed, because you can often hear: "Ugh, that's a shame!", "Ugh, how disgusting!", Etc.

Other scientists believe that speech originated from onomatopoeia (woo-woo theory). In Russian, for example, there are a lot of onomatopoeic words: clap, buzz, rustle, laugh, whistle, ringing and others. Children's speech is especially rich in them: “top-top” - to walk, “tik-tak” - hours, “avka” - dog.

Naturally, one cannot explain the origin of words, the speech of one of these theories; both the one and the other are true to a certain extent — affective exclamations and onomatopoeia served as material for future speech.

Modern science of language believes that when speech began to develop, people first identified the names of things along with their signs and the actions that they produce. In this respect, primitive words are similar to the first words of children's speech, which can only be understood in a specific setting. For example, the word “ma!” Can mean “mama, come here,” and “where is mama?”, And much more.

Linguistics notes that the first step in the development of speech was the dismemberment of primitive words into “indicative” and “denominational”. Indicative words included designations of groups of people, and at first they were collective (they are here, they are there, we are with you, etc.). Among the denomination were the names of objects, their qualities. Unlike modern languages, each word combined many different and often incompatible meanings. In addition, it was an element of figurative description, visual. Soviet linguist II. J. Marr pointed out that in ancient times such diverse objects as “mountain”, “head”, “people” were designated in one word. Examples of such “bundles” of meanings, as Marr called them, can be cited in many and from the languages of modern culturally backward tribes: for example, in one of the native languages of Australia, the word “ingva” means night, sleeping people, edible roots of a water lily, etc. ; the word “mbara” means a knee, a curved bone, a bend of a river, as well as a type of worms, etc. With all the differences of objects, called in one word, they have some kind of common feature. However, it is possible to understand what a person means by using such words only by taking into account the accompanying gestures and the whole situation.

The change of primitive speech with ambiguous figurative concepts comes in a higher level language structure with the distinction between nouns, adjectives, verbs and other parts of speech. Pronouns stand out: me, you, he, she. Primitive speech was understandable only in the appropriate setting and needed accompanying gestures. Now it becomes more independent and independent, which reflects the increased role of human thinking.

When people begin to get acquainted with theories of the origin of speech, then they usually have questions that we are interested to make out here.

Why only man was able to develop articulate speech and abstract verbal thinking?

Why, even for higher animals, such as apes, instinctive sounds and movements are the main means of communication?

Why are children in ways of communication so close to animals and they have so slowly - over the course of several years - speech is formed?

For all three “why?” The answer is the same: it depends on the particular structure of the brain.

IP Pavlov called the brain "the organ of adaptation to the environment." This is a very precise definition. In fact, there are organs that satisfy the needs of the organism itself: the lungs provide gas exchange, the stomach and the intestines digest food, the kidneys perform an excretory function, etc. The brain provides the connection of the organism with the external world around it, makes it possible to adapt to the environment. That is why we can rightfully call it the organ of adaptation.

The simpler the structure of the brain, the more primitive, rougher the form of adaptation of this animal to the environment. On the contrary, the more complex the brain, the more perfect and thinner the mechanisms of adaptation that it creates.

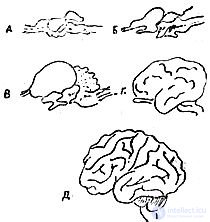

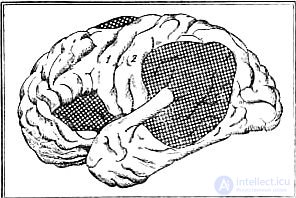

Look at the pic. 2 - it shows the brain of a fish, frog, bird, monkey and, finally, man. Isn't it true, what huge differences even at first glance!

Fig. 2. The brain structure of various animals: A - fish. B - frogs, C - birds, D - monkeys and D - man.

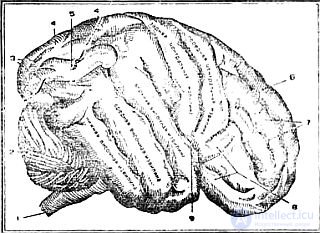

The complication in the structure of the brain is expressed in an increase in its mass relative to body weight (in humans, brain weight is 1 / 46–1 / 50 part of body weight, and in apes - 1/200 part), in the large development of the brain hemispheres and especially the frontal regions (in humans, the frontal lobes occupy 25% of the area of the big hemisphere, and in monkeys - on average 10%), in the appearance of new areas - speech. And how the surface of the brain has increased in man! It gathers in folds and forms numerous furrows and convolutions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The surface of the cerebral hemisphere of the human brain: 1 - spinal cord, 2 - cerebellum, 3 - occipital gyri, 4 - upper and 5 - lower parietal gyrus, 6 - upper, 7 - middle and 8 - lower frontal gyrus, 9 - sylvieva furrow.

A baby will be born with a very immature brain that grows and develops over the years. The newborn has a brain weight of 400 grams, but after a year it doubles, and by the age of 5 it triples! In the future, brain growth slows down, but lasts up to 22-25 years.

The human brain resembles a mushroom in its appearance: the “root” is the so-called brain stem, it consists of the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the visual mounds;The “cap” of the fungus is formed by the big hemispheres - right and left. The small brain, or a cerebellum adjoins to them.

For us, the development of the big hemispheres has a special interest, since our thoughts and feelings arise in them, the work of consciousness is accomplished. Researches of many scientists have shown that there are special zones in the cortex of the big hemispheres that know the function of speech (we will talk about them in detail later).

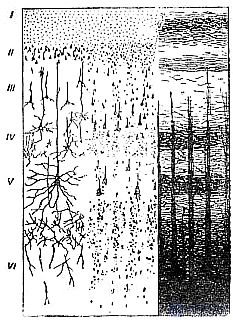

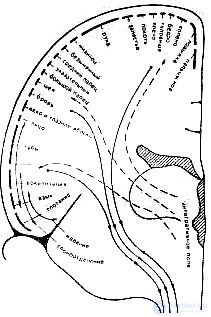

In the cerebral cortex six layers are distinguished (Fig. 4), each layer has its own particular cellular structure. In the human cortex, there are up to 17 billion nerve cells (in apes, there are no more than 3-5 billion of them). The cells are connected to each other by processes, in addition, the entire cortex is penetrated by a network of nerve fibers - in Figure 4 they are shown on the right side. In different parts of the structure of the cortex is very different in the nature of the cells, the thickness of the layers and their distribution - it depends on what kind of work a particular area of the cortex does.

Fig. 4. Микроскопическое строение коры полушарий. Налево — схема распределения клеток, направо — волокон: I — молекулярный слой, II — наружный зернистый слой, III — слой пирамидных клеток средней величины, IV — внутренний зернистый слой, V — слой с крупными пирамидными клетками Беца, VI — полиморфный слой.

В речевых областях разделение коры па слои и созревание нервных клеток завершается в основном к двухлетнему возрасту ребенка, по тонкое строение коры совершенствуется еще на протяжении многих лет.

Thus, the possibilities for the development of speech and abstract verbal thinking in a person are determined by the high development of his brain. The slowness of the formation of the child’s speech function (over several years) is associated with the slow maturation of his brain.

Three-year-old Masha reproachfully asks her teddy bear: “Well, why don't you say so? After all, you have a tongue, so you can talk ?! ”

Some adults, like Masha, imagine that speech is a function of the articulation organs: lips, tongue, larynx, etc.

In fact, it is not.

Speech is first of all the result of the coordinated activity of many areas of the brain. The so-called articulatory organs only carry out orders coming from the brain.

Различают речь сенсорную понимание того, что говорят другие, и моторную произнесение звуков речи самим человеком. Конечно, обе эти формы очень тесно связаны между собой, но все же они различаются. Важно также, что сенсорная и моторная речи осуществляется разными по преимуществу отделами мозга.

Еще в 1861 году французский нейрохирург П. Брока обнаружил, что при поражении мозга в области второй и третьей лобных извилин (на рис. 3 они обозначены цифрами 7 и 8) человек теряет способность к членораздельной речи, издает лишь бессвязные звуки, хотя сохраняет способность понимать то, что говорят другие. Эта речевая моторная зона, или зона Брока, у правшей находится в левом полушарии мозга, а у левшей в большинстве случаев — в правом.

Немного позже — в 1874 году — другим ученым, Э. Вернике было установлено, что имеется и зона сенсорной речи: поражения верхней височной извилины приводят к тому, что человек слышит слова, но перестает их понимать — утрачиваются связи слов с предметами и действиями, которые эти слова обозначают. При этом больной может повторять слова, не понимая их смысла. Эту зону назвали зоной Вернике.

Понимание чужой речи начинается с того, что происходит различение воспринимаемых слов, их узнавание; этот процесс основан на том, что в коре головного мозга вырабатываются нервные связи, благодаря которым различные звукосочетания связываются в слова. В слове звуки следуют один за другим в определенном порядке, и это приводит к установлению связей между ними. Иначе говоря, вырабатывается система связей. Благодаря этому и получается не просто несколько разрозненных звуков, а целое слово. Но не только звуки связываются и слова. Далее эти звукосочетания (уже как целое слово) связываются со многими ощущениями, получаемыми от предмета, который обозначается этим словом. Например, в слове «мама» прежде всего вырабатываются связи между звуками «м-а-м-а»; затем слово «мама» ассоциируется в мозгу ребенка со зрительными, осязательными и другими ощущениями от матери, и вот теперь малыш начинает понимать слово «мама». При другой последовательности этих же звуков получается слово «ам-ам»—здесь тоже вырабатывается система связей между звуками, образуется новое слово, которое далее связывается с комплексом ощущений от еды.

Можно привести множество таких примеров. Но здесь важно подчеркнуть общий принцип развития понимания. Для того чтобы ребенок понял, что слово относится именно к этому предмету, он должен хорошо слышать слово и при этом видеть и трогать предмет. Только после того как зрительные, осязательные и другие ощущения от предмета несколько раз совпадут со слышимым словом, устанавливаются связи между словом и предметом. Теперь достаточно сказать: «Идем ам-ам!» — и ребенок потянется к столу, открывая рот, а мы станем радоваться: «Понял, понял!»

Совершенно так же приобретают названия и действия. Например, малышу говорят: «Покажи носик», — и при этом учат, как показать рукой нос. После того как эти слова несколько раз совпадут с выполнением действия, ребенок уже сам будет проделывать нужное движение в ответ па фразу: «Покажи носик».

Таким образом, понимание речи (работа механизмов приема речи, как иногда говорят) возможно только тогда, когда у ребенка развит слух и в мозгу происходит образование новых нервных связей между слышимыми звукосочетаниями и другими ощущениями.

Местом, где формируются связи между звуками речи, является зона Вернике. Здесь, как в своеобразной картотеке, хранятся все усвоенные ребенком слова (точнее, их звуковые образы), и всю жизнь мы пользуемся этой «картотекой». Если произошло кровоизлияние или другое поражение в области верхней височной извилины, то хранящиеся там звуковые образы слов распадаются, и человек перестает понимать слова'.

Выработка связей между звуками речи и другими ощущениями происходит в иных областях коры мозга, об этом подробнее будет рассказано дальше.

Итак, понимание смысла слов осуществляется мозгом.

«По когда человек сам произносит слова, так уж это-то работа органов речи?» — будут настаивать многие. (Говоря «органы речи», обычно имеют в виду губы, язык, гортань и т. д. Ученые, однако, называют их аппаратом артикуляции, подчеркивая этим термином их второстепенную, исполнительную роль.) Оказывается, и моторная речь — это прежде всего результат деятельности мозга, который является законодательным органом. Там происходит отбор движений, нужных для произнесения тех или иных звукосочетаний, устанавливается их последовательность, т. е. составляется программа, по которой должны действовать мышцы артикуляторного аппарата.

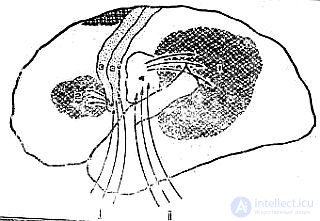

The pronouncing of speech sounds (articulation) requires the coordination of the movement of the lips, tongue, larynx, the participation of oral and nasopharyngeal cavities (Fig. 5), respiratory movements. Try, for example, to pronounce the sound "a" or "l" - and you will immediately feel how many different muscles are activated. Thus, to articulate the “l” sound, the tip of the tongue is pressed against the alveoli of the upper teeth, a stream of air is passed between the lateral edges of the tongue and the upper teeth, the middle part of the tongue is lowered, and its root is lifted; nonverbal muscles are also involved - respiratory and abdominal muscles. All these movements are coordinated with each other, that is, they are produced in a certain sequence, otherwise the sound will not work. See how the articulation mechanism of one sound is just one sound! But if you try to pronounce a sound combination (at least, this seems to be as simple as “mother”), the task will become more complicated many times.

Fig. 5. Diagram showing oral and pharyngeal cavities that amplify sounds arising from vibrations of the vocal cords: 1 - nasal cavity, 2 - oral cavity, 3 - laryngeal cavity, 4 - upper part of nasopharynx, 5 - middle part of nasopharynx, 6 - lower part of the nasopharynx, 7 is the upper jaw, 8 is the soft palate, 9 is the tongue, 10 is the nadgorny cartilage covering the entrance to the larynx.

All work on the formation of motor speech programs occurs in the field of Broca. Therefore, with the defeat of this zone of the cortex, a person can make only inarticulate sounds, and cannot link them into words.

Over the past decades, Canadian neurosurgeon W. Penfield has done a great deal of work on drawing up a “map” of speech zones of the brain. Together with his colleagues G. Jasper and L. Robertson, Penfield performed the following operations: in patients with epilepsy, the focus of the disease was removed.

Among the operated patients there were quite a few such who had an epileptic focus (for example, a scar in the brain tissue after injury, etc.) was in some of the speech areas - then it was necessary to remove it. The patient got rid of epileptic seizures, but he had speech disorders. The state of speech of these patients were long-term observations.

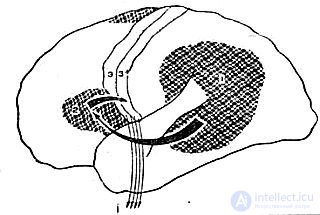

As a result of such observations, Penfield clarified the question of the speech areas of the cerebral cortex - they are shown in Fig. 6

Fig. 6. Map of speech zones of W. Penfield. Hatching in the cage shows the speech zones: on the left - the front (Broca), on the right - the back (Wernicke) and on the top - the extension. The numeral 1 denotes the anterior central gyrus (the area of motor projections), the numeral 2 denotes the posterior central gyrus (the area of sensitive projections).

In addition to the Broca zone (which he called the front speech region) and the Wernicke zone (the back speech region), Penfield discovered an additional, or upper, speech region that does not have such specific functions as the front and back speech regions, but plays a supporting role. He was also able to show the close relationship of all three speech regions, which act as a single speech mechanism. When one of the speech areas of the cortex was removed from a patient, the speech disorders that occurred during this time became less (although they did not pass completely). This means that the remaining speech regions assumed, to some extent, the functions of the remote speech zone. This is a manifestation of the principle of reliability in providing an extremely important speech function for a person. The speech areas in this respect differ from many other areas of the cortex. If, for example, part of the cortex of the visual or auditory areas is removed, impaired functions cannot be restored.

The observations of Penfield and his staff also revealed the unequal role of speech regions. The timing and degree of recovery of speech after the removal of a speech zone show how great the significance of this zone is in the implementation of the speech function. It turned out that speech is restored more easily and more fully when the upper speech zone is removed - which means that it really plays a secondary role.

When you remove the Broca zone violations are persistent and there are very significant defects, but it can still be restored. When the Wernicke zone is removed, and especially if the subcortical structures of the brain are affected, the most severe, often irreversible speech disorders occur. This shows the leading role of the anterior and posterior speech regions for the development and preservation of speech — their loss is only partially compensated.

For the proper flow of a speech act, very precise coordination of the work of speech areas is necessary. Suppose a child wants to call a mother. From the Wernicke zone, where the sound image of the word "mom" is stored, the program of what needs to be said is transmitted to the Broca zone. Here is formed the motor program of pronouncing the word, which enters the region of the motor projections of the articulatory organs. In order to more clearly imagine the ratio of all parts of the speech act, consider it in more detail. First back to pic. 3

Notice the two convolutions of the brain - the anterior and posterior central gyruses. Found them? The anterior central gyrus is the so-called motor projection zone, from here there are orders to make one or another movement; the back central gyrus perceives sensations from muscles. Each muscle of the body is associated with a “sensitive projection” in the posterior central gyrus - thanks to this we feel the position and condition of each part of the body, for example, the arm is bent or straightened, the head is turned, etc .; along the nerve paths, nerve impulses run from the anterior central gyrus to all muscles, which cause one muscle to contract and strain, and the other to relax. From here, teams will go to the muscles of the face, lips, tongue, larynx, respiratory muscles - and the child will utter the word "mother."

In fig. 7 shows a cross section of the anterior central gyrus and dashes - the area of projections of each part of the body. At the very bottom are the representations (projections) of the muscles of the lips, tongue, and larynx. From here, in a given sequence, impulses arrive at the articulatory muscles, and they begin to work.

Fig. 7. Scheme of projections of various parts of the body in the motor area of the cerebral cortex. The size of the line segments in the diagram is proportional to the size of the projections of body parts in the cortex.

Fig. 8 illustrates the sequence of the inclusion of various speech regions during the course of a speech act. This entire complex process is self-regulating, in other words, one link in the act automatically includes the following.

Fig. 8. Diagram of the interaction of speech sections of the cortex during the pronunciation of the word: 1 - Wernicke's zone, 2 - Broca's zone, 3 - projection motor zone, 3a - projection sensitive zone. The arrows indicate the direction of propagation of the pulses; i denotes the flow of impulses to the speech muscles.

All speech areas are in the left hemisphere of the brain. The right hemisphere can also "learn" to control speech, that is, it can form speech zones; this happens in left-handers, as well as in cases where the left hemisphere has suffered. It is quite often observed in birth trauma or severe damage to the left hemisphere in early childhood. There are descriptions of such cases and at an older age. So, L. Wooldridge describes a case when after a complete removal of the left hemisphere (about a tumor) in a 13-year-old boy, a right-handed person completely recovered his speech after a short time.

The question of the extent to which the right hemisphere becomes the leader of left-handers is being studied by many researchers, but there is still no consensus on this issue. Penfield, for example, believes that left-handed people also retain the predominant role of the left hemisphere. However, another Canadian scientist, C. Milner, examined 123 left-handed patients and came to the conclusion that in people with left-handedness, the leading role of the left hemisphere is noted in a small number of cases — they usually have the function of the right hemisphere. Moscow morphologist E. P. Kononov, studying the brain structure of children, found that by the age of two there is a clear separation of the layers of the cerebral cortex, the appearance of pronounced cell features in each layer (differentiating them) in the speech areas (in right-handers in the left hemisphere, and in left-handers - in the right).

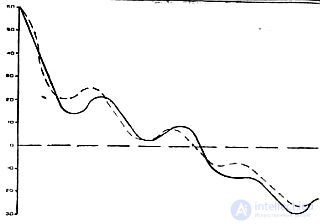

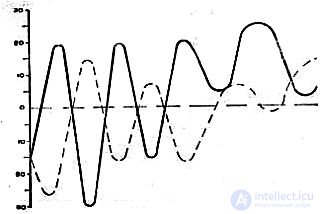

In normal speech, the work of both hemispheres is coordinated very precisely. Leningrad physiologists V.V. Belyaev, I.V. Danilov, and I.M. Cherepanov studied how symmetric points in the right and left hemispheres of the human brain work at rest and when he says: scientists recorded the brain currents and then mathematically processed these records. They found that, in healthy people, always - both at rest and during speech - the activity of symmetric points in the frontal, temporal and occipital areas in both hemispheres is precisely coordinated, but the flow of nerve processes in the left hemisphere is 3–4 thousandths of a second ahead of processes in the right. In patients with stuttering, these authors found a divergence in time of the activity of symmetrical points up to 44 milliseconds, while the right hemisphere began to outpace the left hemisphere! These differences are clearly visible on reducible curves (Fig. 9 and 10).

Fig. 9. The curve showing the work of symmetrical is accurate in the left and right hemispheres of the brain during speech. The dotted line shows the process in the left, solid line - in the right hemisphere.

The word articulation occurs in the process of the respiratory act, in the expiratory phase. In order to pronounce a long sound combination (“come here,” “give a pen”, etc.), an extended exhalation is necessary. And indeed, with speech breathing, exhalation is 5–8 times longer than the inhalation.

Fig. 10. The same is with the patient with stuttering. The designations are the same.

During speech, each breathing cycle (inhalation - exhalation) takes twice as long: instead of 16-18 cycles per minute, only 8-10 are obtained. Speech breathing also requires more active participation of all muscles, including the intercostal and abdominal. Normal speech breathing in children is produced gradually in the process of learning speech. Talking, we never think about which muscles and in what sequence we use, how we need to breathe - we have these mechanisms that act automatically. Only in the case of pathology - in the formulation of sound speech in deaf-and-dumb children, in stuttering and other speech disorders, when these automatisms are not developed or broken, the patient has to think about them and create them under the control of consciousness.

Doesn’t it now become obvious that the body of speech is, in fact, the brain - it is the understanding of audible words, the programs of movements that are needed for the articulation of sounds, and the sound combinations of speech are formed in it, the commands for speech muscles come from here. Now that we have understood this, we can move on to the following questions.

We have already said above: in order for a person to understand a word, it is necessary to form connections in his brain between the sounds from which this word is composed, that the selection of movements of the articulatory apparatus and their sequence are also ensured by the connections developed in the brain. What are these connections and how do they arise?

The brain responds to all influences from the external environment (visual, sound, temperature, and others) and from the organism itself (hunger, thirst, etc.). These answers, or reflexes, are innate (they are also called instinctive) and acquired in life experience, worked out.

To obtain innate reflexes, no preliminary training, no training, no special conditions are required, therefore IP Pavlov called them unconditional. Thus, the newborn responds by sucking on touching the lips, squeezes its eyes tight when bright light enters the eyes, and so on, without any training. This happens because the neural pathways (connections) along which innate reflexes are carried out are already formed during the development of the nervous system and they are ready and able to function for the birth of a child.

But in the third month of life, the baby begins to make sucking movements at the sight of a bottle of milk - this is already the result of the baby’s life experience, and not a congenital reaction. To produce such a reflex, certain conditions are needed: the type of bottle of milk must coincide several times with the food unconditional reaction, the type of bottle must precede the food reaction, etc. That is why the reflexes produced are called conditional. The ways in which they are carried out, are also developed and are called conditional connections.

The number of unconditioned reflexes is rather limited. The most important of them are food, protective, approximate, sexual, parental, imitative. They constitute the basis on which activities, which are ambitious in terms of complexity and volume, develop new, conditioned reflexes. The number of new, conditioned reflexes produced on the basis of each unconditioned reflex is immense, in fact, it cannot be counted.

IP Pavlov wrote about the reflexes being developed: “Here arises through conditional communication, association of the new principle of nervous activity: signaling of few unconditional external agents to an infinite mass of other agents, constantly being analyzed and synthesized, giving the possibility of a very large orientation in the same environment and thus a much larger adjustment. " (FOOTNOTE: I. P. Pavlov. Complete. Collected works. M. - L., Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1949, vol. 3, p. 475.)

What are the reflexes are speech? Of course, both innate and developed reflexes are involved in the implementation of the speech act. The first, the so-called preverbal reactions - gut, pipe. For all properly developing children, they manifest themselves in the same time frame and in the same form, which means that they are not the result of training. Deafness happens even among deaf people from the birth of children (true, it soon fades away). Congenital reactions include the first manifestations of onomatopoeia in children from two to seven months: when imitating articulatory mimicry, the child involuntarily makes a corresponding sound.

Gradually, between the audible sounds and those movements of the lips, tongue, larynx, etc., which are necessary for the pronunciation of these sounds, conditional connections are established. Now, having heard the sound of speech and not seeing the facial expression of an adult, the child tries to reproduce it - sound imitation becomes conditionally reflexive. These conditional relationships are developed very early - in the first months of the life of children.

The mechanism of the conditioned reflex provides the development of understanding of words. Studies have shown that understanding words requires the participation of both hemispheres. This is very convincingly shown in the observations of American neurosurgeons and neuroscientists R. Sperry, X. Gozzanigo and T. Boden. In patients with epilepsy, they performed operations of complete separation of the cerebral hemispheres (in order to mitigate seizures), that is, they cut all the connections between the right and left hemispheres. After the patients fully recovered after surgery, they were examined for their speech state. In addition, brain currents were recorded to determine how the right and left hemispheres behave during these observations.

It turned out that the expression of their thoughts with the help of words or letters in these patients was solely due to the left hemisphere (all these patients were right-handed). The understanding of words spoken by other people or read was equally related to the work of both hemispheres. In samples where it was necessary to associate a word with an object (to name it), group or select objects of the same category, both hemispheres turned out to be equally active, active.

If we compare these facts with what we see in the development of understanding in children, then the reason for the activity of both hemispheres is very easy to understand. Indeed, in the process of understanding, that is, connections of the word with the subject, connections of the visual-auditory, visual-tactile, motor-auditory, etc., are involved. In other words, understanding is the result of the development of a large number of conditioned connections between many areas of the cerebral cortex in both hemispheres.

When a child begins to pronounce words, it is also always the result of learning, that is, the result of the development of systems of conditional relations. It uses both the connections that were obtained by combining the sounds of speech and the movements of the articulatory organs, and those that are produced by combining the sounds of speech among themselves. Each word is a stereotype of certain sound combinations, each phrase is a stereotypical combination of words. The sequence of elements included in the stereotype is fixed, and if one element of the stereotype is given, the child reproduces the rest. For example, you say “tick” - “so”, the child finishes the usual combination of the words “tick-so”.

But that is not all. It must be borne in mind that the path from the center to the periphery, that is, from the brain to the speech muscles, is only part of the mechanism of speech. The other part is feedback. They go from the periphery, from the muscles to the center, and report to the brain about the position of all the muscles involved in articulation at each time interval. This allows the brain to make the necessary amendments to the work of the articulatory organs even before the sound is pronounced. This is a kind of muscular control over the processes of articulation. In addition, there is auditory control - the word that the child pronounces is compared with the standard stored in the Wernicke zone, an example of this word. В отличие от мышечного контроля, слуховой действует несколько позже, когда слово уже произнесено. На рис 11 показано направление потоков двигательных импульсов от мышц и слуховых импульсов от уха во время речи. В нашем объяснении движение нервных импульсов от мозга к мышцам и от мышц к мозгу показано отдельно (см. рис. 8 и 11), на самом же деле они протекают почти одовременно, с разницей в тысячные доли секунды.

Слуховой и двигательный контроль у детей можно наблюдать постоянно. Вот Леша (2 года 2 месяца) пытается произнести слово «шишка»: «сишка»… «шиска»… Мальчик уже запомнил слово «шишка», т. е. эталон в зону Вернике заложен, но артикуляция еще не отработана, и при сопоставлении образца со звукосочетаниями «сишка», «шиска» и т. п. получается несоответствие. Ребенок теперь улавливает его и поэтому снова и снова пытается произнести это трудное для него слово.

Fig. 11. Схема направления потоков импульсов по обратным связям при произнесении слова:

1 — зона Вернике, 2 — зона Брока, 3 — проекционная, двигательная зона, 3а — проекционнная чувствительная зона, 4 — слуховая область. Римские цифры обозначают: I — поток мышечных импульсов от речевых мышц, II — поток слуховых импульсов от уха.

Когда словесные шаблоны уже зафиксировались в мозгу, дети подолгу с трогательным усердием стараются выговорить то или другое слово, подгоняя его под образец. Посмотрите, как реагирует малыш на попытки взрослого подделаться под его речь. Миша двух с половиной лет вместо «обратно» говорит «абанта». Когда же во время прогулки отец шутливо предлагает: "Ну, а теперь пошли абанта», — Миша сердито возражает: "Что за абанта?! Надо говорить аба… аба… абанта», лицо его делается плаксивым. Слуховой контроль подсказывает мальчику, что «абанта» не очень-то похоже на «обратно», но добиться правильной артикуляции он пока не может. Бабушка Вити (ему 2 года 7 месяцев) носит пенсне, которое часто теряет и то и дело ищет. При очередной потере Витя сочувственно спрашивает: «Опять песны потеряла?» — «Да, — смеется бабушка, — опять песны потеряла!» Витя морщится и укоризненно говорит: «Ну кто говорит песны? Скажи пес… пёс…, пес… Скажи как надо!» Подобные случаи представляют собой яркую иллюстрацию того, как идет у ребенка сличение слышимого звукосочетания с тем эталоном слова, который был ранее закреплен. (Кстати, но показывает также, почему недопустимо подделываться под детскую речь, коверкать слова. Если вы имеете привычку сюсюкать с ребенком, то это нарушает процесс выработки словесных эталонов у него.)

Итак, можно сказать, что речь имеет в своей основе как врожденные рефлексы, так и системы выработанных, т. е. условных рефлексов. Они и составляют тот механизм согласования, который делает возможной координированную деятельность многих отделов мозга, необходимую для того, чтобы человек мог говорить.

По ведь люди не только говорят словами, они и думают словами. Давайте посмотрим, что это такое—словесное мышление.

И. П. Павлов подчеркивал, что основная задача мозга — восприятие и переработка сигналов, поступающих из внешней среды.

Мозг животных отвечает лишь на так называемые непосредственные (т. е. прямо действующие на нервную систему) раздражители: то, что животное сейчас видит, слышит, обоняет и т. д. Отдельные ощущения и комплексы ощущений — из них слагаются представления, впечатления — являются сигналами, по которым животное ориентируется в окружающем мире. Одни сигналы предупреждают об опасности, другие — о получении пищи и т. д. Кошка дает агрессивную реакцию при виде собаки, но с мурлыканьем бежит навстречу своей хозяйке; комплекс ощущений от собаки служит сигналом того, что надо приготовиться к защите, а комплекс ощущений от хозяйки — сигналом того, что сейчас дадут поесть и приласкают.

Отражение в мозге действительности в форме непосредственных ощущений И. П. Павлов назвал первой сигнальной системой действительности, а сами ощущения — первыми сигналами действительности. Он указывал, что первая сигнальная система у нас, людей, общая с животными, так как и у нас есть ощущения, представления, впечатления от того, что нас окружает, с чем мы соприкасаемся. Вы любуетесь формой и красками цветка, чувствуете его аромат, т. е. получаете непосредственные ощущения, первые сигналы действительности. Вы почувствовали запах розы или лимона, и у вас сейчас же возникло представление о самом цветке и плоде — это следы непосредственных ощущений (вернее, их комплексов). Однако у человека все явления действительности отражаются в мозге не только в форме ощущений, представлений и впечатлений, но и в форме особых условных знаков — слов.

«Слово составило вторую, специально нашу (т. е. человеческую. — М. К.) сигнальную систему действительности, будучи сигналом первых сигналов»,[1] — говорил И. П. Павлов. Он подчеркивал, что, с одной стороны, слово удаляет нас от действительности, т. к. здесь отсутствуют непосредственные ощущения (например, слово «роза» не передает ни формы, ни аромата этого цветка, так же как слово «лимон» не вызывает ни зрительных, ни вкусовых, ни обонятельных ощущений — эти слова могут лишь оживить следы ранее полученных непосредственных ощущений), но, с другой стороны, слово дает больше сведений о предмете, чем непосредственные ощущения, — слова «лимон» или «роза» совмещают в себе множество ощущений от множества лимонов, множества роз — они стали понятиями.

Именно потому, что слова обобщают множество непосредственных раздражителей, они могут вызывать все те реакции, которые вызывали эти раздражители. Слово «мама», например, обобщает все те ощущения, которые ребенок получает от матери — ее внешности, голоса, прикосновений и т. д. Няня говорит двухлетнему Коле: «Мама идет», — и он радостно бросается к двери, как будто уже увидел ее. Вместе с тем, слово «мама» для Коли уже не просто обозначение одного определенного лица. В этом же возрасте, увидев кошку с котятами, он воскликнул: «Кися — мама!» Ребенок смог перенести слово на новый объект, т. е. оно приобрело для него уже обобщающее значение, стало понятием.

Как видно из определений, которые давал И. П. Павлов, слово можно оценивать как обобщающий сигнал («сигнал сигналов») лишь в том случае, если оно обозначает не один какой-то предмет, а множество их. Одно и то же слово «цветок» может быть сигналом одного предмета (когда ребенок познакомился еще только вот с этим одним цветком) и понятием (когда слово стало обозначать то существенное, что ребенок выделил во множестве виденных им цветов).

Когда слово обозначает только один предмет или действие по отношению к одному предмету («покажи носик!», «дай ручку!»), мы не можем говорить, что это настоящее полное понимание смыслового содержания слова. Для маленького ребенка есть конкретная ложка, елка, есть мама, но нет еще ложки вообще, елки вообще и т. п. — нет общих понятий. Для него понятны фразы «покажи носик», «дай ручку», но слова «давать», «показывать» тоже не стали еще понятиями, Значение слов в этот период для ребенка можно сравнивать со значением, которое они имеют для животных. Собака, например, дает правильные реакции на многие словесные сигналы («Дай лапу!», «К ноге!» и т. д.), но для нее это, собственно, не слова, а звуковые сигналы (как, например, свист, стук). Для маленьких детей слова тоже пока являются лишь звуковыми сигналами и не имеют того обобщающего значения, которое они получают позже. Значит, реакции малыша на слова в тот период, о котором здесь говорится, еще нельзя считать проявлением деятельности второй сигнальной системы. Поэтому же нельзя расценивать как проявление второй сигнальной системы каждое слово, которое произносит ребенок. Например, малыш 1 года 6 месяцев, услышав слова матери, что она безумно устала, повторяет за ней: «Безюмана, безюмана!» Конечно, такое повторение слов есть простое звукоподражание, как у попугая или скворца. Иногда ребенок выучивает и повторяет слово как будто совершенно осмысленно. Лева в 1 год 2 месяца при прощании научился махать ручкой и говорить: «Ди-да-да», т. е. до свидания. Юля в 1 год, когда ее усаживают за стол, кричит: «Дай-дай-дай!» Можно привести множество таких примеров, когда ребенок произносит слова, вполне соответствующие по смыслу ситуации. Но нельзя забывать, что ребенка усердно учили произносить именно эти слова и именно в данной ситуации. Порой ребенок произносит эти слова совсем некстати, и вот тут-то и выясняется, что настоящего понимания слова еще нет, а есть заученная звукоподражательная реакции.

Нередко приходится наблюдать, что такая реакция возникает на какой-то элемент той обстановки, с которой связано слово. Тот же Лева энергично машет рукой и говорит «ди-да-да» (до свидания), когда при нем открывают дверцу шкафа или буфета. Из этого ясно видно, что двигательная и речевая реакции мальчика еще не имеют смысла прощания, они являются лишь подражанием действиям взрослых и их словам.

Это наблюдается и у более старших детей. Иногда обнаруживается, что дети повторяют слова, которые для них не имеют не только обобщающего значения, но ничего еще не обозначают. Вот Лена (3 года 4 месяца) декламирует стихотворение «На парад идет отряд». Оно звучит у нее так:

Аппаят идет наряд,

Левой-правой, левой-правой,

Он уже дырявый и т. д.

Очевидно, что для девочки это просто набор звукосочетаний, среди которых выделяются два-три слова, имеющие для нее смысл, но они никак не вяжутся друг с другом.

Другой случай: в старшей группе детского сада готовят к празднику инсценировку, где «командир» вскакивает верхом на лошадь-палочку и командует: «По коням!» Исполнитель этой роли в день выступления заболел, и его заменил другой мальчик, который очень эмоционально провел роль, но, вскакивая на лошадь, закричал не «По коням!», а «Покойник!». Никого из «солдат» такая команда не смутила, они весело вскочили на «коней» и поскакали.

Как выяснилось позже, ни один ребенок в группе не понимал, что значит «по коням», хотя все прекрасно знали слово «конь». Новое ударение сделало слово неузнаваемым, и оно действовало просто как звуковой сигнал.

Все это показывает, что не только для самых маленьких, но и для более старших детей слово не всегда имеет сигнальное значение, а тем более — широкое обобщающее значение…

У здорового взрослого человека вторая сигнальная система является главенствующей, она определяет его поведение, но и первая сигнальная система также постоянно дает о себе знать. Ведь мы всегда осознаем, насколько наши мысли, умозаключения соответствуют реальной действительности, — в этом и проявляется влияние первой сигнальной системы.

У некоторых людей отражение действительности происходит преимущественно через слова — «сигналы сигналов», а непосредственные зрительные, звуковые и другие образы внешнего мира у них сравнительно слабы и бледны. Такие люди могут плакать, читая чеховского «Ваньку», и при этом в жизни быть равнодушными к детям.

У других людей, напротив, непосредственные ощущения и впечатления более ярки и сильны. Соответственно и роль первой сигнальной системы в высшей нервной деятельности этих людей значительно больше, однако и у них вторая сигнальная система является главенствующей.

Первый тип, характеризующийся относительной слабостью первой сигнальной системы, И. П. Павлов назвал «мыслительным», а второй тип, отличающийся относительно сильной первой сигнальной системой, — «художественным».

Еще раз хочется подчеркнуть, что в таком делении речь идет лишь о сравнительной силе первой сигнальной системы у людей разного типа, а не о сравнительной силе первой и второй сигнальных систем у них.

Характеризуя различные типы, И. П. Павлов говорил: «…один хорошо думает, но не конкретно, не реально, связь между первой и второй сигнальной системами у него довольно рыхлая, а другой, наоборот, думает также умно, также по логике, но имеет постоянную тенденцию за словом видеть реальное впечатление, т. е. первые сигналы, — он с окружающей действительностью сносится сильнее, чем первый. Так что и для нормальных умов степень отношения к действительности дает себя знать».

Довольно редко встречается средний, или гармонический, тип, у которого сила обеих сигнальных систем очень хорошо уравновешена.

Чрезвычайно важно отметить, что формирование у человека того или иного типа нервной деятельности — художественного, мыслительного или гармонического — Павлов связывал с условиями жизни и воспитания, т. е. социальными воздействиями. Он подчеркивал, что в силу того, что образ жизни разных слоев населения на протяжении многих поколений отличался, люди и разделились на мыслительный, художественный и средний типы.

Изучение высшей нервной деятельности ребенка показывает, что только на первом году жизни можно наблюдать проявление первой сигнальной системы в «чистом виде» — когда ребенок еще не понимает слов и не говорит сам. В этот период поведение его определяется тем, что доступно слуху, зрению, обонянию, вкусу и т. д.

Но с момента, когда начинает развиваться вторая сигнальная система, она начинает накладывать отпечаток и на все непосредственные ощущения, получаемые ребенком. В лаборатории нам пришлось наблюдать один очень яркий пример такого влияния второй сигнальной системы. У трехлетнего Ромы вырабатывали условный пищевой рефлекс на самый обыкновенный звонок (как только он прозвенит, ребенок получал конфетку), но он был довольно громким; такой же звонок, но тихий был тормозным раздражителем — на него конфеты не было. К общему удивлению, Рома очень долго путался, и мы никак не могли получить у него хорошего различения этих двух звонков. Наконец, спросили мальчика, какой звонок громкий, а какой — тихий. Он ответил правильно. Но дальше выяснилось, что громкий похож на папин звонок (в дверь), а тихий похож на мамин; конфеты же всегда приносит мама, а не папа. Обычный непосредственный раздражитель оказался не таким уж обычным, так как ребенок по-своему осмыслил его. Значит, даже у таких маленьких детей нельзя выделить чистых «первых сигналов»: к ним добавляется и их изменяет действие слов.

Конечно, вторая сигнальная система не сразу приобретает свою доминирующую роль. В разные возрастные периоды соотношение сигнальных систем у детей неодинаково. В раннем детстве резко превалирует первая сигнальная система; вторая еще только начинает формироваться и пока не может оказывать большого влияния. Для маленьких детей непосредственные ощущения и впечатления гораздо более сильные раздражители, чем слова. В лаборатории Н. И. Красногорского (СНОСКА: Н. И. Красногорский был учеником И. П. Павлова и одним из первых начал изучать работу мозга у детей методом условных рефлексов.) на детях от трех до семи лет провели такие исследования. При зажигании синего света дети получали засахаренную клюкву, а при зажигании красного — ничего не получали.

Когда у детей таким образом были выработаны условный пищевой рефлекс на синий свет и его задержка, торможение — на красный, приступили к самой интересной части работы: при включении синего света ребенку говорили, что горит красный, и, наоборот, при включении красного света говорили, что горит синий свет. Оказалось, что у всех ребятишек 3–4 лет реакция получалась не на слова, а на тот свет, который горит на самом деле. Когда вспыхивала синяя лампочка, ребенок открывал рот, чтобы получить клюкву, хотя ему говорили, что горит красный свет. Некоторые даже спорили: «Нет, ты путаешь — это синий огонек, а не красный!» Значит, для детей младшего дошкольного возраста действие непосредственного раздражителя (света, который они видели) было сильнее влияния слова. Дети в возрасте около пяти — пяти с половиной лет путались и реагировали то на слова, то на цвет горящей лампочки. Это означает, что, хотя вторая сигнальная система у них уже сформировалась и давала о себе знать, непосредственные ощущения (первая сигнальная система) были пока сильнее. Дети же шести лет и старше в этих опытах почти в 60 % проб реагировали именно на слово, а не на горящий свет, т. е. слово становилось для них более сильным сигналом. Нужно все же оговориться, что довольно быстро реакции этих детей корригировались, подправлялись непосредственными ощущениями: при повторных пробах старшие дети тоже начинали ориентироваться на цвет загоревшейся лампочки. Иначе говоря, первая сигнальная система давала знать, насколько характер словесного сигнала был согласован с реальностью.

Эти отношения очень ярко проявляются и в жизни, а не только в опытах. Вот две девочки — Марина 8 лет и Таня 9 лет — переехали на дачу и с любопытством смотрят на цепную собаку, охраняющую двор. Невдалеке прибита дощечка с надписью: «Осторожно, злая собака», но на самом-то деле Тарзан очень добродушный пес. Он виляет хвостом, ложится кверху лапами и всячески заигрывает с девочками, но они боятся подойти. Когда их стали уговаривать, что Тарзан их не тронет, девочки возразили: «Но ведь написано же, что он злой. Что он сию минуту ласкается, так это ничего не значит, — он и хватить может, раз вообще-то злой!» Здесь слово оказалось сильнее непосредственного впечатления. Однако в этом возрасте обе сигнальные системы уже хорошо связаны между собой, через пару дней девочки убедились, что надпись на дощечке несправедлива, и дружба с Тарзаном наладилась.

Этот пример показывает не только характер взаимодействия сигнальных систем, но и то, в чем именно заключается сила слова: оно сразу дает общее представление о предмете и отодвигает на второй план непосредственные впечатления. Это допускает гораздо более быструю и точную ориентацию в явлениях.

Регулирующая роль второй сигнальной системы, близкая к той, которая наблюдается у взрослых, может быть получена у детей примерно к 10 годам, но не окончательно. В переходном возрасте (с 11–13 лет у девочек и с 13–15 у мальчиков) отношения сигнальных систем вновь меняются. По наблюдениям болгарского ученого П. Балевского, речь у подростков в эту пору замедляется, словарь как бы становится беднее, для того чтобы получить исчерпывающий ответ на какой-нибудь вопрос, нужно повторить его несколько раз, задать дополнительные вопросы. Это заставляет предполагать ослабление деятельности второй сигнальной системы, и как результат этого — усиление функций первой сигнальной системы. Экспериментальные данные свидетельствуют о том, что действительно скорость образования условных рефлексов на непосредственные (зрительные, слуховые, осязательные) раздражители теперь снова возрастает, в то время как выработка условных рефлексов на словесные сигналы затрудняется. Это связано с гормональными перестройками в организме, которые влекут за собой ослабление высшего функционального уровня деятельности коры.

After a year or two, the interaction of signaling systems characteristic of an adult person is firmly established again and now, that is, with the prevalence of the role of the second signaling system. The first signal system may be stronger for some, weaker for others, but now it is under the control of the second signal system for all.

Here I would like to draw attention to another very important circumstance in practical terms. Parents in the family and caregivers in children's institutions make a lot of efforts to give more knowledge to children as soon as possible, to form their systems of concepts. In other words, work with children is mainly aimed at developing and training the second signal system. So, children artificially create a tendency to form a “mental” type of nervous activity. This tendency is especially pronounced for children growing up in a big city. Meanwhile, even I. P. Pavlov emphasized that the “mental” type is a depleted type, since, due to the weakness of direct sensations, the life of these people passes by nature and all that art provides.

In a family where a child (most often the only one) does a lot - read to him, tell, etc., - all immediate sensations and impressions are artificially slowed down, and therefore they are scant and pale. Thus, the second signaling system early acquires the meaning that is unusual for it in this period of the child’s development, and the harmonic ratio of “sensual” perception of the world and abstract verbal thinking is disturbed.

The five-year-old Natasha saw a bouquet of peonies. “Mom, what do you think, would it be inconvenient to live in such a Thumbelina flower?” Mom was not upset that the flowers caused only a literary association in her daughter, but did not attract her attention by themselves. They continued to talk only about what kind of flowers would be a suitable home for Thumbelina, Mom and herself only glimpsed a wonderful bouquet.

Here is another case. The little girl on the bus pulls her father’s sleeve: “Dad, look at the Neva!” - “Well? Neva as Neva. “Oh no,” the girl insists excitedly. “When we went to our grandmother, the Neva was gray, and now it’s blue-blue!” But Dad didn’t share his daughter’s excitement or interest, he only angrily remarked: “Look at what dirty glass you’d have, and you’re pressing your nose.”

In cases similar to those described, the parents miss a very convenient time in order to focus the child’s attention on the immediate sensations that he is receiving now. If the child is interested in something, it is especially easy to do. Therefore, it is very important not to suppress children's reactions to what they see, feel, but to strengthen them, showing interest, surprise, etc.

In children's institutions (nurseries, kindergartens), much attention is now paid to the so-called “sensory education,” that is, education of various forms of analysis of environmental phenomena: visual, auditory, visual-spatial, etc. This is essentially the case. training the first signal system. But in the children's team it is not always possible to have sufficient individual work with each child in this direction. Therefore, parents during walks, playing with the baby at home should try to pay attention to this

side of its development. It is always useful to show the child the clouds, the color of the sky, the flowers that he passes by, give them a sniff, and at home ask him to remember what kind of flowers they were, maybe draw them. Such exercises will help to strengthen the direct sensations and impressions, and this will lay a good foundation for the subsequent formation of the second signal system.

Now, when we got acquainted in general with what speech is and what role it plays in the development of abstract verbal thinking, let's follow in more detail the course of its development in a child.

one

IP Pavlov pointed out that with the leading role of the second signal system, the nature of its interaction with the first may be different among different people.

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogy and didactics

Terms: Pedagogy and didactics