Lecture

The formation of the old Russian state. One of the largest states of the European Middle Ages became in the IX-XII centuries. Kievan Rus. Unlike other Eastern and Western countries, the process of forming Russian statehood had its own specific features. One of them - the spatial and geopolitical situation - the Russian state occupied a middle position between Europe and Asia and did not have pronounced, natural geographic boundaries within the vast plain area. In the course of its development, Russia acquired the peculiarities of both eastern and western state formations. In addition, the need for constant protection from external enemies of a large territory forced nations of different types of development, religion, culture, language, etc., to create a strong state power and to have considerable militia.

The closest to the historical truth in the coverage of the initial phases of the development of Russia, apparently, was one of the early Russian historians monk-chronicler Nestor. In The Tale of Bygone Years, he presents the beginning of the formation of Kievan Rus as a creation in the 6th century. powerful alliance of Slavic tribes in the Middle Dnieper. This union adopted the name of one of the tribes "Ros", or "Rus". The union of several dozen separate small forest-steppe Slavic tribes in the VIII-IX centuries. turns into superethnos with the center in Kiev. Russia of this period on the occupied area was equal to the Byzantine Empire.

Further, the chronicler Nestor claims that the tribes of the Ilmen Slavs who were at enmity with each other, the Krivichi and Chud, invited the Varangian prince to restore order. Prince Rurik (? - 879) allegedly arrived with the brothers Sineus and Truvor. He himself ruled in Novgorod, and the brothers - in Beloozero and Izborsk. The Varangians laid the foundation of the grand-ducal dynasty of Rurikovich. With the death of Rurik with his young son Igor, the guardian of the king (prince) Oleg (? - 912), nicknamed the Prophet , becomes the guardian . After a successful march on Kiev, he managed to unite in 882 Novgorod and Kiev lands into the old Russian state - Kievan Rus, with its capital in Kiev, by definition the prince - “the mother of Russian cities”.

The initial instability of the state association, the desire of the tribes to maintain their isolation sometimes had tragic consequences. Thus, Prince Igor (? - 945), while collecting traditional tribute (polyude) from subordinate lands, demanding a considerable excess of its size, was killed. Princess Olga, Igor's widow, brutally avenging her husband, still fixed the size of the tribute, setting "lessons", and determined the places (graveyards) and the timing of her collection. Their son Svyatoslav (942-972) combined state activity with a significant commander. During his reign, he annexed the lands of the Vyatichi, defeated Volga Bulgaria, subjugated the Mordovian tribes, defeated the Khazar Kaganate, conducted successful military operations in the North Caucasus and the Azov coast, repelled the onslaught of the Pechenegs, etc. But returning from the march to Byzantium, Svyatoslav’s squad was defeated by the Pechenegs , and Svyatoslav himself killed.

The unifier of all the lands of the Eastern Slavs as a part of Kievan Rus was the son of Svyatoslav - Vladimir (960-1015), nicknamed by the people "Red Sun", who built a number of border fortresses from the raids of numerous nomads to strengthen the state’s borders.

Norman theory. The narration of the chronicler Nestor about the vocation of the Varangians on the Russian land later found a rather contradictory interpretation of historians.

The founders of the Norman theory are considered to be German historians Gottlieb Bayer, Hered Miller and August Schlozer. Being invited to Russia during the rule of Anna Ioannovna and the rise of the Bironovshchina, the authors of this “theory” and her supporters exaggerated the role of the Scandinavian soldiers in the development of statehood in Russia. It was this “theory” that was raised on the shield by the fascists in order to justify the attack in 1941 on our homeland and accusing Russia of inability to develop independently.

Meanwhile, the state as a product of internal development cannot be brought in from the outside. This process is lengthy and complex. For the emergence of statehood, appropriate conditions, the awareness of the majority of members of society of the need to limit tribal power, property separation, the emergence of tribal nobility, the emergence of Slavic teams, etc. are necessary.

Of course, the fact of attracting the Varangian princes and their teams to the service of the Slavic princes is not in doubt. The relationship between the Vikings (the Normans from the scandal "man of the north") and Russia is indisputable. The invited leaders of the Rurik mercenary (Allied) ratification in the future, obviously, acquired the functions of arbitrators, and sometimes - civil authority. The subsequent attempt of the chronicler in support of the ruling dynasty of Rurikovich to show her peaceful, not aggressive, violent sources is quite understandable and understandable. However, quite controversial, in our opinion, is the “argument” of the Normanists that the Varangian king Rurik was invited with the brothers Sineus and Truvor, the fact of which history no longer reports anything. Meanwhile, the phrase "Rurik came with relatives and retinue" in ancient Swedish language reads like this: "Rurik came with blue hus (his kind) and tru thief" (true retinue).

In turn, the extreme point of view of anti-Normanists, who prove the absolute identity of Slavic statehood, the denial of the role of Scandinavians (Varyags) in political processes contradicts the well-known facts. Mixing of clans and tribes, overcoming the former isolation, the establishment of regular intercourse with near and far neighbors, and finally, the ethnic association of the North Russian and South Russian tribes (all this) are characteristic features of the advancement of Slavic society to the state. Developing similarly to Western Europe, Russia simultaneously approached the line of formation of a large early medieval state. And the Vikings (Vikings), as in Western Europe, stimulated this process.

At the same time, Normanist statements are difficult to call a theory. They actually have no analysis of sources, a review of known events. And they testify that the Vikings in Eastern Europe appeared when the Kiev state was already formed. It is impossible to recognize the Vikings as creators of statehood for the Slavs for other reasons. Where are any noticeable traces of the influence of the Vikings on the socio-economic and political institutions of the Slavs? In their language, culture? On the contrary, there was only Russian in Russia, not Swedish. And the contracts of the tenth century. with Byzantium, the embassy of the Kiev prince, which included, by the way, the Varyags of the Russian service, were drawn up only in two languages - Russian and Greek, with no trace of Swedish terminology. At the same time, in the Scandinavian sagas service to the Russian princes is defined as the surest way to gain fame and power, and Russia itself is a country of countless riches.

Social system. Gradually, in Kievan Rus, a state management structure was formed, initially, in many respects similar to the Western institution of vassalage, which included the concept of freedom, granting autonomy to vassals. Thus, the boyars - the highest stratum of society - were vassals of the prince and were obliged to serve in his army. At the same time, they remained full masters in their own land and had less notable vassals.

The Grand Duke ruled the territory with the help of a council (Boyar Duma), which included senior members of the armed forces — local nobility, representatives of cities, and sometimes clergy. The most important state issues were resolved at the Council as an advisory body under the prince: electing a prince, declaring war and peace, concluding treaties, issuing laws, reviewing a number of court and financial cases, etc. The Boyar Duma symbolized the rights and autonomy of vassals and had the right to "veto". The younger squad, which included the boyars' children and youths, did not include the courtyard servants, as a rule, into the Council of the Prince. But in resolving the most important tactical issues, the prince usually consulted with the retinue as a whole. With the participation of princes, noble boyars, and representatives of cities, feudal congresses also gathered , at which issues affecting the interests of all principalities were considered. A management staff was formed, in charge of legal proceedings, collection of duties and tariffs.

The main unit of the social structure of Russia was the community - a closed social system recognized to organize all kinds of human activity - labor, ceremonial, cultural. Being multi-functional, it was based on the principles of collectivism and equalization, it was the collective owner of land and land. The community organized its inner life on the principles of direct democracy (election, collective decision-making) - a kind of, veche ideal. In fact, the polity was kept on the contract between the prince and the national assembly (veche). The composition is veche-democratic. The entire adult male population with noisy approval or objection made the most important decisions on issues of war and peace, managed the prince's table (throne), financial and land resources, sanctioned fees, discussed legislation, biased the administration, etc.

An important feature of Kievan Rus, formed due to the constant danger, especially from the steppe nomads, was the general arming of the people, organized according to the decimal system (hundreds, thousands). In the city centers there were tysyatskie - the leaders of the military city militia. It was the numerous militia that often decided the outcome of the battles. And it did not obey the prince, but veche. But as a practical democratic institution, it is already in the XI century. It gradually began to lose its leading role, retaining its strength for several centuries only in Novgorod, Kiev, Pskov and other cities, continuing to exert a noticeable influence on the course of the social and political life of the Russian land.

Economic life. The main economic activities of the Slavs were farming, animal husbandry, hunting, fishing, and handicraft. Byzantine sources characterize the Slavs as people who are tall, bright, living sedentary, as they "build houses, carry shields and fight peshes".

The new level of development of the productive forces, the transition to plowed, sedentary and mass farming, with the formation of relations of personal, economic and land dependence, gave a new feudal character to the new production relations. Gradually, the subsampling system of farming is replaced by a two- and three-field, which causes the seizure of communal lands by strong people - the process of land fodder takes place.

K X-XII centuries. in Kievan Rus develop large private land tenure. A form of land ownership becomes feudal patrimony (fatherhood, that is, fatherly possession), not only alienated (with the right of sale and donation), but also inherited. The patrimony could be princely, boyar, monastic, church. The peasants living on it not only paid tribute to the state, but became dependent on the feudal lord (boyar), paying him a rent for the use of land or working off the serfdom. However, a significant number of residents were still communal peasants independent of the boyars, who paid tribute in favor of the state to the grand duke.

The key to understanding the socio-economic system of the ancient Russian state can be largely polyude - collecting tribute from the entire free population (“people”), chronologically covering the end of VIII - the first half of the tenth century, and locally to the twelfth century. It was actually the most naked form of domination and subordination, the exercise of the supreme right to land, the establishment of the concept of nationality.

Collected in enormous amounts of wealth (food, honey, wax, fur, etc.) not only met the needs of the prince and his retinue, but also accounted for a rather high share of ancient Russian exports. To the collected products were added slaves, people from prisoners or people caught in heavy bondage, who were in demand in international markets. The grandiose, well-guarded military-trade expeditions that fall on summer time brought the export part of the polyudia along the Black Sea to Bulgaria, Byzantium, and the Caspian Sea; Russian land caravans reached Baghdad on their way to India.

The peculiarities of the socio-economic structure of Kievan Rus were reflected in Russkaya Pravda, a true set of ancient Russian feudal law. Striking a high level of lawmaking, a legal culture developed for its time, this document was valid until the 15th century. and consisted of separate norms of the “Law of the Russian”, “Most Ancient Pravda” or “Pravda Yaroslav”, Additions to the “Pravda Yaroslav” (provisions on collectors of court fines, etc.), “Pravda Yaroslavichi” (“Pravda Russkaya Zemlya”, approved by the sons Yaroslav the Wise), the Charter of Vladimir Monomakh, which included the “Charter on cuts” (percent), the “Charter on procurement”, etc .; "Extensive Truth."

The main trend in the evolution of Russkaya Pravda was the gradual expansion of legal norms from the princely law to the environment of the squad, the determination of fines for various crimes against the person, and a colorful description of the city to attempts to codify the norms of the early feudal law that had developed by that time, covering every resident of the state from the princely warriors and servants , feudal lords, free rural communes and citizens to slaves, servants and not possessing property and who were in full possession of their lord, in fact their slaves. The degree of lack of freedom was determined by the economic situation of the peasant: smerds, ryadoviks, procurement farmers, who for one reason or another fell into partial dependence on the feudal lords, worked a considerable part of the time on the patrimonial lands.

In Pravda Yaroslavichi the device of the patrimony as a form of land ownership and the organization of production was reflected. Her center was the mansion of the prince or boyar, the house of his entourage, stables, barnyard. Led the fiefdom of the firelash - the princely butler. Princely driveway was collecting taxes. The work of the peasants was led by war (plowed) and rural elders. There were artisans and artisans in the area of self-sufficiency.

Kievan Rus was famous for its cities. It is no coincidence that foreigners called her Gardariki - the country of cities. At first they were fortresses, political centers. Overgrowing with new tenements became the focus of handicraft production and trade. Even before the formation of Kievan Rus, the cities of Kiev, Novgorod, Beloozero, Izborsk, Smolensk, Lyubech, Pereyaslavl, Chernihiv, and others formed on the most important water trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks." In the X-XI centuries. a new generation of political and trade-craft centers is being created: Ladoga, Suzdal, Yaroslavl, Murom, etc.

In Kievan Rus, more than 60 types of crafts (carpentry, pottery, linen, leather, blacksmithing, weapons, jewelry, etc.) were developed. The products of artisans sometimes spread tens and hundreds of kilometers around the city and abroad.

Cities also took over trade and exchange functions. In the largest of them (Kiev, Novgorod), there was a wide and regular trade on the rich and vast bazaars, and nonresident and foreign merchants resided permanently. Of particular importance in the economic life of Kievan Rus acquired external economic relations. Russian merchants "Ruzar" were well known abroad, they provided them with significant benefits and privileges: contracts 907, 911, 944, 971. with Byzantium and others. Among the five most important main trade routes Tsargrad-Byzantine, Trans-Caspian-Baghdad, Bulgarian, Reginsburg and Novgorod-Scandinavian, the first two initially had the greatest value.

Interestingly, domestic trade in Russia, especially in the XI-X centuries, was mostly of a “exchangeable” character. Then, along with the exchange, the money form appears. Initially, cattle (leather money) and furs (martens kuna fur) acted as money. Russkaya Pravda mentions metal money. The main accounting metal currency was the hryvnia kun (elongated silver ingot). Hryvnia kun was subdivided into 20 legs, 25 kunas, 50 slices, etc. Having existed in the Old Russian market until the XIV century, this monetary unit was supplanted by the ruble. The minting of his coin in Russia began in the X-XI centuries. Along with it were in circulation and foreign coins.

The political and socio-economic life of the Slavs of the ancient Russian state was complemented by spiritual life.

Christianization of Russia

Christianization of Russia. With the formation and development of the ancient Russian state, the formation of a single Russian nation, paganism, with its many deities in each tribe, traditions of tribalism and blood feuds, human sacrifices, etc., ceased to respond to the new conditions of social life.

At the beginning of his reign, the attempts made by the Kiev prince Vladimir I (980-1015) at the beginning of his reign to somewhat streamline the rituals, raise the authority of paganism, turn it into a single state religion were unsuccessful. Paganism lost its former naturalness and attractiveness in the perception of a person who overcame tribal narrowness and narrowness.

The neighbors of Russia - the Volga Bulgaria, who professed Islam, the Khazar Kaganate, who converted to Judaism, the Catholic West and the center of Orthodoxy - Byzantium, tried to gain unanimity in the face of the rapidly gaining strength of the Russian state. And Vladimir I, at a special Council in Kiev, after listening to ambassadors from neighbors, made a decision - to get acquainted with all religions and choose the best one, send Russian embassies to all lands. As a result, Orthodox Christianity was chosen, which amazed the Russians with the splendor of the cathedrals, the beauty and solemnity of services, the grandeur and nobility of the Orthodox Christian idea - a kind of idyll of forgiveness and unselfishness.

The first reliable information about the penetration of Christianity into Russia dates back to the 11th century. Christians were among the warriors of Prince Igor, Princess Olga, who was baptized in Constantinople and encouraged her son Svyatoslav, was a Christian. In Kiev there was a Christian community and the Church of St. Elijah. In addition, the long-standing trade, cultural and even dynastic ties (Vladimir Krasnoe Solnyshko himself was married to the sister of the Byzantine emperors Anna) of Kievan Rus and Byzantium played an important role in this choice. By the way, the close kinship of the ruling dynasties, in turn, excluded the vassal dependence of the young Russian state on the Byzantine center of Christianity.

Prince Vladimir of Kiev, baptized in 988, began to energetically establish Christianity on a national scale. By his order, the inhabitants of Kiev were baptized in the Dnieper. On the advice of Christian priests, mostly immigrants from Bulgaria and Byzantium, the children of the "best people" were handed over to the clergy for teaching literacy, Christian dogmas and education in the Christian spirit. Similar actions were carried out in other lands. In the north of the country, where pagan traditions remained strong, attempts at baptism sometimes met with difficulties and led to uprisings. So, to conquer the Novgorodians, it took even a military expedition of the Kievites, led by the uncle of the Grand Duke Dobrynya. And over a number of subsequent decades and even centuries in rural areas there was a dual faith - a kind of combination of previous ideas about the world of the supernatural, pagan mounds, violent holidays of the native antiquity with elements of a Christian worldview, worldview.

The adoption of Christianity was of great importance for the further development of the ancient Russian state. It ideologically consolidated the unity of the country. Conditions were created for full cooperation of the tribes of the East European Plain in the political, commercial, cultural fields with other Christian tribes and nationalities on the basis of common spiritual and moral principles. Baptism in Russia created new forms of inner life and interaction with the outside world, tore Russia away from paganism and the Mohammedan East, bringing it closer to the Christian West.

Christianity in Russia was adopted in the eastern, Byzantine version, which later received the name - Orthodoxy, i.e. true faith. Russian Orthodoxy guided people towards spiritual transformation. However, Orthodoxy did not provide incentives for social progress, for the transformation of people's real life. In the future, such an understanding of the goals of life began to diverge from the European type of attitude towards transformative activity, and began to slow down development.

Muscovy (lat. Moscovia) is the political and geographical name of the Russian state in Western sources, used with varying degrees of priority in parallel with the ethnographic name “Russia” (lat. Russia) from the 15th to the beginning of the 18th century. Initially, it was the Latin name of Moscow (for comparison: Latin Varsovia, Kiovia) and the Moscow Principality], later in a number of states of Western and Central Europe it was transferred to a single Russian state, formed around Moscow under Ivan III. Various researchers believe that the use of this name was facilitated by Polish-Lithuanian propaganda, which deliberately preserved the terminology of feudal fragmentation, denying the legitimacy of the struggle of Ivan III and his successors for the reunification of the lands of Rus'. The Latinism Muscovy was not used as a self-name, having entered the Russian language no earlier than the 18th century as an incompletely mastered borrowing.

Origin and distribution

During the era of confrontation between the Grand Duchy of Moscow, which united North-Eastern Rus' around itself, and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which united South-Western Russia around itself, the ancient concept of “Rus” (in Europe Russia, sometimes Ruthenia, Rossia or Greek Ῥωσία) continued to be used contemporaries, but in the conditions of its political and geographical division it needed additional clarification. Often, starting from the 14th century, clarification was carried out according to the Byzantine model - Great and Little Rus'. In other sources - such as, for example, on the map of the Venetian monk Fra Mauro - the distinction was made using the names White, Black and Red Rus'. It is noted that at the dawn of Russian-Italian relations in the era of Ivan the Great, in written sources originating from Italy, we are talking either simply about Russia or about White Russia, while Ivan III himself is called the “Russian Emperor.”

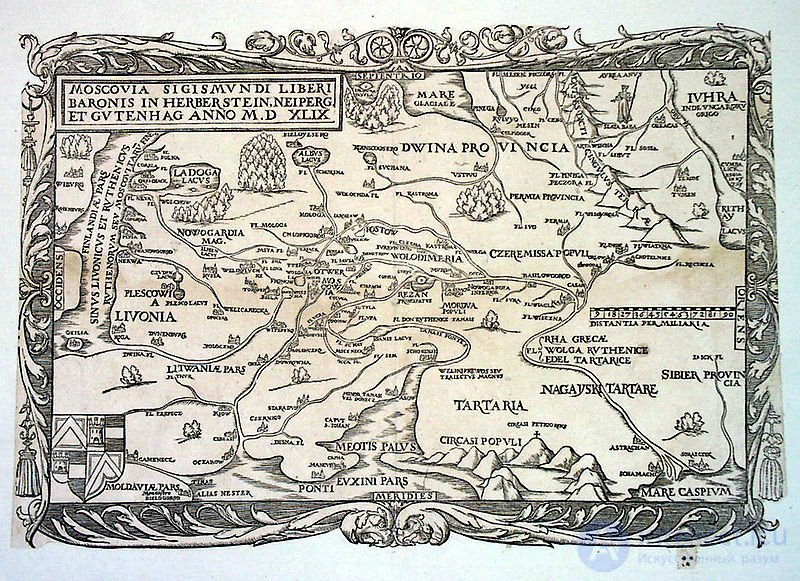

An example of the use of Moscovia, Herberstein, 1549. The coast of the Baltic Sea is called the Livonian-Russian coast (Sinus livonicus et ruthenicus), as well as the land of the Russians or Muscovites (Ruthenorum seu Moscovitarum fine). The Russian (ruthenice) names of the Volga and Don are listed.

At the same time, starting from the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, the concept of “Muscovy” was rapidly spreading in the European political and geographical lexicon. Various researchers believe that it arose under the influence of Polish-Lithuanian propaganda, which rejected the right of the Russian state to all ancient Russian lands (part of which from the 13th-14th centuries was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, later - the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) and sought to consolidate this name only for “their” part of Russia Already from the beginning of the 15th century, the term “Russia” on Polish maps designated exclusively the lands of Southwestern Russia, and Lvov, the capital of the “Russian Voivodeship,” was indicated as its main city. At the same time, the lands of North-Eastern Rus' were called nothing more than “Muscovy”. Focusing on the former feudal narrow regional nomenclature, this persistently implemented term was intended to emphasize the limitation of the power of the head of state within the boundaries of the Moscow principality and rejected any hints of the legitimacy of the struggle for the unification of Rus' around Moscow.

Historian Anna Khoroshkevich noted that the name "Muscovy" began to prevail in countries that received information from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland, primarily in Catholic Italy and France. In the countries of Northern Europe that had more direct communication with the Russian state, as well as at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, the correct ethnographic name “Russia” or “Russia” prevailed, although the name “Muscovy” penetrated there too. One of the clear examples of the “change” of the name, according to Khoroshkevich, are the protocols of the secretary of the Venetian Signoria Marino Sanuto, in which, starting in 1500, there is a gradual transition from the name (White) Russia to Muscovy. The historian connects this with the strengthening of Polish-Lithuanian propaganda on the eve of and during the Russian-Lithuanian war of 1500-1503, when a diplomatic conflict flared up between Moscow and Vilna over the claim to the title of Ivan III “sovereign of all Rus'”, containing a program for the unification of all Russian lands, including those who were part of Lithuania.

As Boris Florya writes, in addition to political circumstances in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the last quarter of the 16th century, the idea of “Russians” and “Muscovites” as two different peoples took shape, which also influenced the self-awareness of the East Slavic population of the state. In the previous era, there were only prerequisites for this based on the different socio-political structures of the two states, which, however, did not yet provide grounds for recognizing them as signs of belonging to different ethnic communities. Thus, the Polish historian Matvey Mekhovsky in his “Treatise on the Two Sarmatias” (1517) wrote that the inhabitants of Mo

Comments

To leave a comment

The World History

Terms: The World History