When we say that a person has deceived himself, we mean a completely different situation. When self-deceiving a person does not realize that he is lying to himself, and does not know what motivated his deception. I believe that self-deception occurs in fact much less frequently than those stated by those who want to justify their wrong actions in this way and thus avoid the well-deserved punishment. When studying the actions that led to the crash of the Challenger space shuttle, the question arises whether people who decided to launch the shuttle can be considered victims of self-deception, despite serious warnings of possible danger. Otherwise, how can you explain the fact that, knowing perfectly about risk, people still allowed the launch?

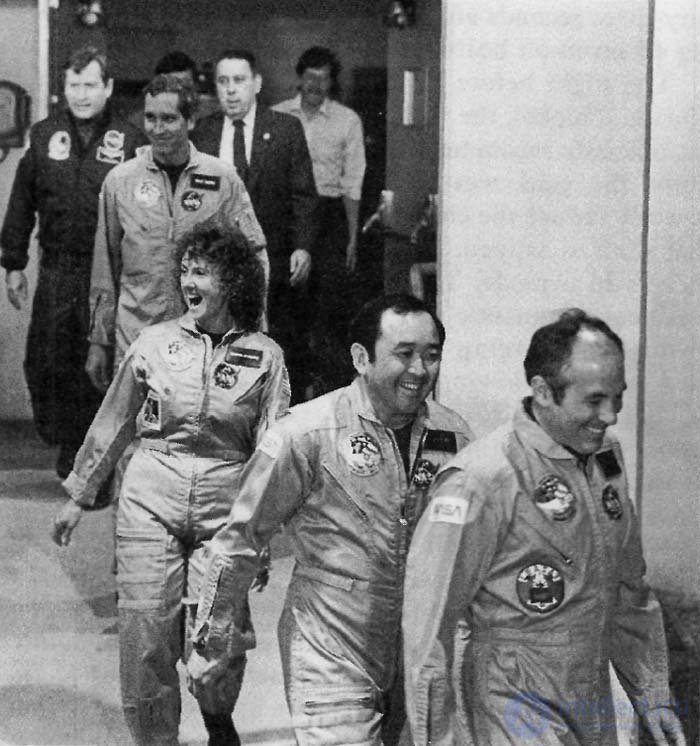

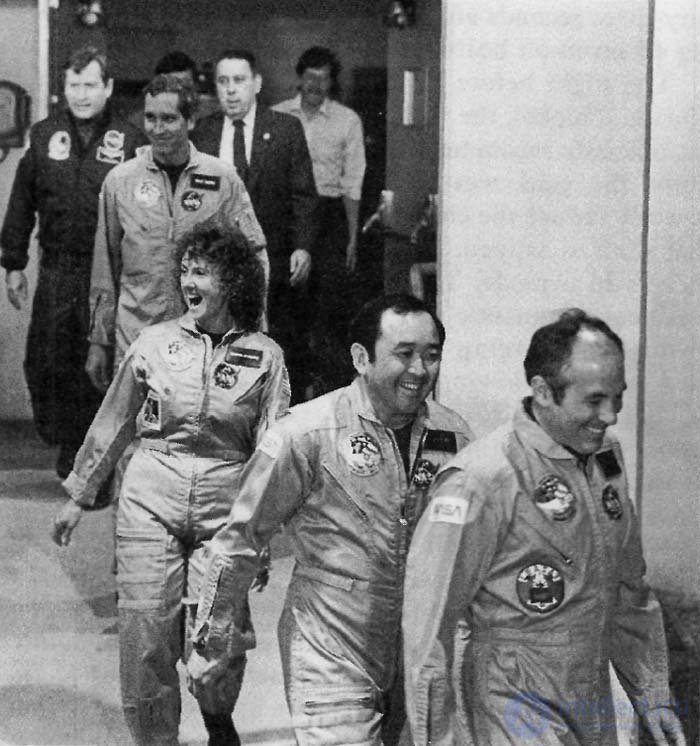

On January 28, 1986, millions of viewers watched the launch of the space shuttle. This launch was widely advertised also because one of the crew members was school teacher Krista Makolif. There were many schoolchildren among the viewers, including students of Ms. McAuliffe. She was supposed to conduct a lesson from outer space. But only seventy-three seconds after launch, the ship exploded, and all seven people on board died.

On the evening before the launch, a group of engineers from Morton Thiokol, which manufactured the starting engines, officially recommended that the launch be postponed, because, according to the forecast, cold weather was expected the next day and this could lead to a strong decrease in the elasticity of the rubber insulation rings. As a result, there could be a fuel leak and an explosion of starting engines. Thiokol engineers called the National Aeronautics and Space Research Committee (NASA) and unanimously insisted that the launch scheduled the next morning was postponed.

The launch date has been postponed three times already, despite promises from NASA that the space shuttle will fly according to an established schedule. NASA manager Lawrence Malloy, objected to the engineers at Thiokol, arguing that there was not enough reason to think that, due to the cold weather, the isolation rings could refuse. That evening, Malloy spoke with the manager of Thiokol, Bob Lund, who later testified to the presidential commission appointed to investigate the Challenger disaster. Lund said that that evening Malloy advised him to think "as a manager," and not "as an engineer." Lund apparently did so and changed his mind, disregarding the objections of his own colleagues. Malloy also contacted one of the vice-presidents of Thiokol, Joe Kilminister, and asked him to sign permission to launch. Joe Kilminister signed the resolution at 23:45 and faxed the appropriate recommendations to NASA. Nonetheless, Allan MacDonald, director of Thiokol’s engine department, refused to sign an official launch approval. (He had to leave Thiokol in two months.)

Later, the presidential commission found that the four chief executive officers of NASA, who were responsible for allowing each launch, did not report that that evening, when the launch decision was made, between the engineers of the company "Thiokol" and the NASA group of engine managers had disagreement. Robert Sick, shuttle manager at Kennedy Space Center; Gene Thomas, Shuttle Manager in Kennedy Center; Arnold Aldrich, the space communication systems manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, and director of the shuttle Moore later stated that they were not informed about the objections of Thiokol’s engineers against the launch decision.

How could Malloy send a shuttle into space, knowing that it could explode? This is understandable only if, being under pressure, he became a victim of self-deception and really believed that engineers too exaggerated the risk. If Malloy really became a victim of self-deception, then is it fair to blame him for the wrong decision? Suppose someone lied to him and said that there was no risk at all. In this case, of course, we would not blame him for making the wrong decision. Is there any difference compared to self-deception? I think not, but only if Malloy was really deceived. However, how can one establish whether this was self-deception or a cleverly grounded lie?

To answer this question, let us compare what we know about Malloye with one of the examples of obvious self-deception, which is often given by experts who study self-deception

[259] .

A person who is incurably ill with cancer, having believed that he will recover, retains his false faith, despite the numerous signs of a rapidly progressing inoperable malignant tumor. Malloy also maintained a false belief, believing that the launch of the shuttle was not dangerous. (I think that the variant according to which Malloy knew for sure that the ship would explode should be ruled out.) The cancer patient believes that he will be cured, despite strong evidence to the contrary. The cancer patient sees that he is becoming weaker, that the pain is getting worse, but he insists that these are only temporary relapses of the disease. Malloy also persisted in his false belief, although the facts contradicted this. He knew the opinion of the engineers, but he neglected this fact, considering it to be an exaggeration.

However, all that has been said so far is not yet the answer to the question of who should regard a cancer patient and Malloy as deliberate liars or victims of self-deception. The main sign of self-deception is that his victim is not aware of the motives that cause her to cling to her false faith

[260] .

The cancer patient does not realize that his self-deception is motivated by his inability to cope with fear. This element — the unconsciousness of the motivation for self-deception — was absent in Malloy. After advising Landa to think “as a manager,” he thereby demonstrated a quite clear understanding of what needs to be done to believe in the expediency of launching.

The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman, a former member of the presidential commission investigating the Challenger catastrophe, described the type of managerial thinking that influenced Malloy: “After completing the Moon’s research program ... it was necessary to convince Congress that there was a project which can only implement NASA. For this, it was necessary — at any rate then it was clearly necessary — to exaggerate: to exaggerate the efficiency of the shuttle, to exaggerate the frequency of its flights, to exaggerate safety, to exaggerate the great scientific discoveries that would be made ”

[261] . Newsweek Magazine wrote: “In a sense, NASA became a victim of the hype created by itself, making it seem like a space flight is just as common as a bus ride.”

Malloy was just one of many NASA employees who supported this exaggeration. He was probably afraid of the reaction of Congress to the fourth cancellation of the flight of the shuttle. This would play the role of anti-advertising, contrary to all exaggerations of NASA, and could affect future allocations. In any case, the fact that another postponement of the launch date would ruin the reputation of the shuttle did not cause any doubts. The risk associated with weather conditions was only an opportunity, not an undoubted fact. Even the engineers who objected to the launch were not absolutely sure that an explosion would certainly occur. Some of them later said that even a few seconds before the explosion they hoped that, perhaps, everything would be fine.

Malloy should be condemned for having misjudged the situation, giving management more importance than engineering warnings. Engine safety specialist Hank Shui, who, at the request of NASA, studied the history of the disaster, concluded: “This is not a design defect. An erroneous decision was made. ” To explain or justify the wrong decisions self-deception should not be. It is also necessary to condemn Malloy for the fact that he did not inform the authorities, who have the authority to make the final decision on the launch, of complete information. Feynman offers a convincing explanation of the reasons that prompted Malloy to take responsibility: “Guys who want to force the congress to approve their projects do not want to hear such conversations (about problems, risks, etc.). It’s better not to hear anything, then they can be more “honest” - they don’t want to lie to Congress! Therefore, their behavior changes very soon: all these "bumps" and mid-level managers begin to suppress all unwanted information like this: "I don’t need to tell me about your problems with some kind of isolation, otherwise I will have to ban the flight and deal with it problems "or:" No, no, you have to fly, fly, fly at whatever cost "or:" Do not tell me about it; I do not want to hear it. " At the same time, perhaps, they do not force them to “keep silent” directly, but they do not encourage messages that are actually the same thing ”

[262] .

Malloy’s decision not to inform management of the sharp differences over the launch of the shuttle can be viewed as a lie through silence. Remember my definition (Chapter 1, “Lies. Information Leakage and Some Other Signs of Deception”): one person intentionally misleads another person without any prior notification of this. It does not matter how the deception is done - by false statements or by keeping silent about important facts. These are only technical differences, the result is one.

This notice is the decisive point. Unlike a person posing as another, an actor is not a deceiver precisely because viewers know about his game. The situation when playing poker is somewhat more ambiguous, since the rules allow for some types of deception (for example, bluff), as well as when buying property, when you should not expect the sellers to honestly tell the real price from the very beginning. If Feynman is right and the top management of NASA did not encourage interaction, in fact, discarding any information from below, then this can be considered an actual notification. Malloy, and perhaps others at NASA, knew that bad news or difficult decisions should not be sent up. If this is so, then Malloy should not be considered a liar because he did not inform the top leaders, since they allowed such a deception.

I believe that the leaders in this case fully share the responsibility with Malloy. Top management is responsible not only for the final decision on the launch, but also for creating an atmosphere of interaction. And it was this that contributed to the occurrence of the circumstances that led to the error and to the fact that Malloy preferred to make a decision without putting the top management to the notice.

Feynman notes the similarities between the situation in NASA and what the middle-level officials who participated in the Iran-Contra affair felt (for example, Poindexter about the message to President Reagan about his actions). If subordinates believe that a person with a higher authority should not talk about things that are undesirable (as a result, the top official always has a convenient opportunity to deny his involvement), this leads to the destruction of power. Former President Harry Truman rightly said: “This is where the responsibility ends.” The president or senior executive should monitor the situation, assess the situation, make decisions and take responsibility for them. Another way of leadership can bring temporary advantages, but it threatens any hierarchical organization, contributing to the excess of power and creating an atmosphere of sanctioned lies.

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of lies

Terms: Psychology of lies