The contradictory testimony of the candidate for the Supreme Court of Justice Clarence Thomas and the law professor Anita Hill, which were given in the fall of 1991, contain a number of very eloquent testimonies of the possibilities of lying. Their dramatic confrontation, televised on television, occurred just a few days before the Senate had to approve the appointment of Thomas as a member of the Supreme Court. Professor Hill addressed the Senate Justice Commission with a statement that from 1981 to 1983, when she was an assistant to Clarence Thomas, first in the civil rights department of the Ministry of Education, and then when he became head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, she was sexually abuses on his part. "He told me about sexual intercourse, which he saw in pornographic films, including such things as sexual intimacy between women and animals, as well as about films with group sex or scenes of violence ... He told me about pornographic publications, which depicted individuals with large penises or large breasts, committing sexual acts in various poses. On several occasions, Thomas was very figurative in telling me about his own sexual exploits ... He also said that if I told someone about his behavior, I would ruin his career. ” She testified quite calmly, avoiding contradictions, and seemed very convincing to many.

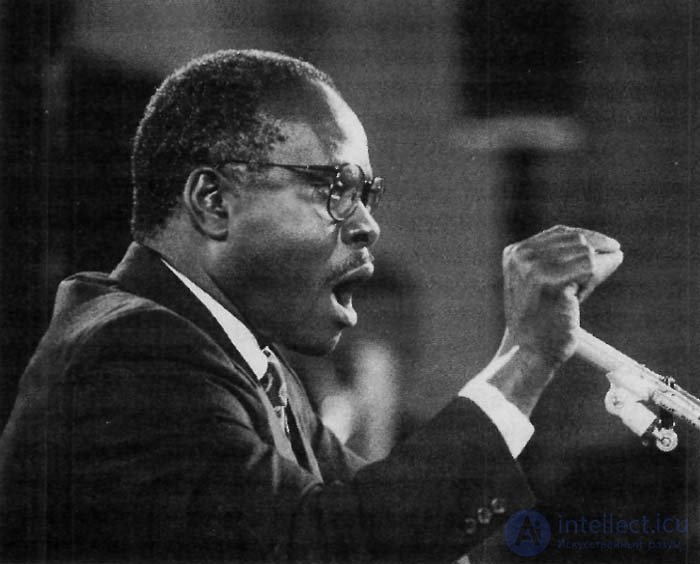

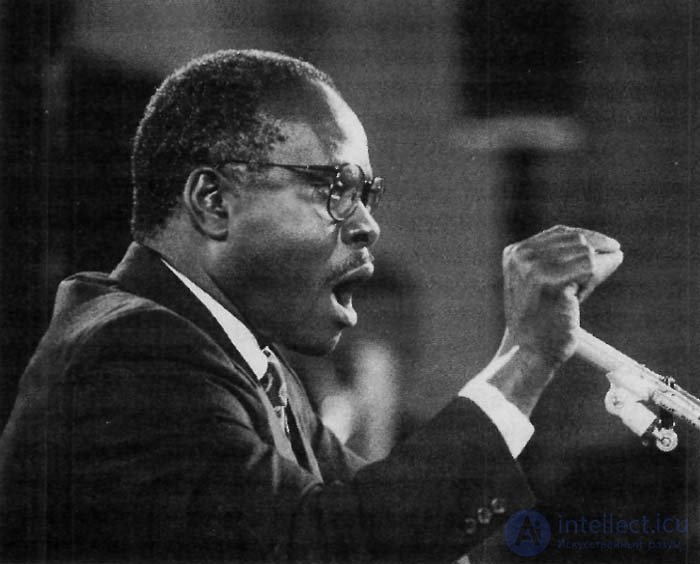

Then, after the end of her testimony, Judge Thomas completely denied all her accusations: “I didn’t do and didn’t say any of the things that Anita Hill imputes to me.” He said: “I would like to begin with an unequivocal, categorical denial of all the accusations made against me today.” In a fit of righteous indignation caused by such a clear undermining of his reputation, Thomas stated that he was the victim of an attack motivated by racist considerations. He continued: “I can’t just rightly dismiss these accusations, as they correspond to the worst stereotypical notions of a black man in this country”. Complaining about the Senate, which forced him to go through such torture, Thomas said: "I would prefer a killer bullet than a life in such a hell." He called the hearing of his case "sophisticated lynching of arrogant blacks."

Time magazine then wrote on the front page: “Two credible and clearly articulating their thoughts to the witness in the face of the whole nation express incompatible views on events that took place almost ten years ago.” Columnist Nancy Gibbs wrote: “Even after hearing all the evidence, you cannot be completely sure that they themselves know how it really was. And who is the liar of the epic scale? ”

I pursue narrower goals and focus only on Hill’s and Thomas’s behavior during testimony, not touching Thomas’s address to the commission before Anita Hill’s case, the life history of Thomas and Hill, or the testimony of other witnesses. Considering only their behavior patterns, I did not find any particular specific information and noted only the fact that both did not escape, and that they both spoke and behaved quite convincingly from the attention of the press. But their confrontation contains several lessons about lies and demeanor of deception in general.

It was not easy for any of them to deliberately lie in the face of the whole nation. For both the rate was very high. Imagine how it would end if the mass media and the American people, rightly or wrongly, were considered a liar to one of them. But this did not happen; both looked like they were telling the truth.

Suppose Hill spoke the truth, and Thomas made a conscious decision to lie. If he turned to chapter 2 of my book, “The Psychology of Lies,” he would have found advice: the best way to hide the fear of being caught in a lie is to disguise it under a different emotion. Using the example from John Upday's Let's Get Married novel, I described how Ruth could have fooled her husband by being angry that he didn’t believe her and forcing him to defend himself. That is exactly what Clarence Thomas did. He became very angry, and not at Anita Hill, but at the Senate. He received an additional advantage, winning the sympathy of all those who are angry with politicians, acting in the role of David, fighting the powerful Goliath.

Just as Thomas would lose audience sympathy if he attacked Hill, senators would lose public sympathy if they attacked Thomas, a black man who says he is lynched for insolence. If he were going to lie, then it would make sense not to be present at the testimony of Anita Hill, so that the senators could not directly ask him questions about this testimony.

Although this line of reasoning should appeal to Thomas’s opponents, it still does not prove that he lied. He might as well have attacked the Senate Commission and was telling the truth. If Hill was a fraud, then Thomas had every right to be furious because the Senate, in the presence of the public, listened to its tales invented by its political opponents who could not legally prevent its appointment. If Hill was a liar, Thomas could be so upset and angry that he simply would not watch her testimony on television.

Could Anita Hill Lie? I think this is unlikely, because if she had lied, she should have been afraid that she would not be believed, and there were no signs of fear in her behavior. She testified with calm and confident restraint and almost without any signs of emotion. But the lack of behavioral signs of deception does not mean that a person is telling the truth. Anita Hill had time to prepare and rehearse her story. It is possible that it was precisely because of this that she achieved the persuasiveness of her speech, although this is unlikely.

Most likely Thomas was a liar, not Anita Hill. But there is a third possibility, which I consider still the most likely. None of them spoke the truth, and at the same time nobody lied. Suppose that actually something less happened than Professor Hill said, but more than Judge Thomas was willing to admit. If its exaggeration and its denial were repeated many times, then by the time we were present at their testimony, there was almost no chance that each of them remembers that he does not speak quite the truth.

Thomas could forget what he was doing, and even if he remembered, he subjected memories to severe censorship. Then his anger about her accusations is fully justified. From his point of view and according to his memories, he does not lie, he speaks the truth. And if Hill had any reason to be offended by Thomas, a real or imaginary, such as a scornful attitude or an insult, then over time the real incident could be inflated, exaggerated and decorated with all the colors of the rainbow. Then she also spoke the truth that she remembered and in which she believed. This is similar to self-deception, but still differs from it in that in this case, false beliefs are formed gradually, over time, by repetitions, at each of which revision occurs. However, authors who write about self-deception may find this difference unworthy of special attention.

In this case, it is impossible to determine by the manner of conduct which of the stories is true: which of them lied or who did not tell the whole truth? Nevertheless, when people have deep convictions regarding sexual abuse, the moral character of members of the Supreme Court, senators, men, and so on, it is difficult for them to bear the inability to determine the truth. Faced with such an ambiguous situation, most people solve the problem, fully assuring themselves that they can only by one manner of behavior determine who is telling the truth. In fact, it turns out that the person to whom they are more sympathetic from the very beginning wins.

This does not mean that the behavioral signs of deception are useless, you just need to know when they can be beneficial and when they are not, and how to relate to a situation when we cannot determine whether a person is lying or telling the truth. For accusations of sexual abuse, there is a statute of limitations of ninety days. One of the most justified reasons for introducing such a restriction is that the closer the actual events, the easier it is to notice the behavioral signs of deception. If we had the opportunity to see how they testified a few weeks after the alleged encroachment, then it would be much more likely to determine by their behavior which of them is telling the truth. And perhaps the charges themselves would have been different.

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of lies

Terms: Psychology of lies