Lecture

In this chapter, we will have to put two main questions to the theories investigating the problem of experience. The first of these is associated with an understanding of the nature of critical situations that give rise to the need for experience. The second relates to the concepts of these processes themselves.

Stress

Frustration

Conflict

A crisis

As already noted, the critical situation in the most general terms should be defined as a situation of impossibility , i.e. such a situation in which the subject is faced with the impossibility of realizing the inner necessities of his life (motives, aspirations, values, etc.).

There are four key concepts by which critical life situations are described in modern psychology. These are the concepts of stress, frustration, conflict and crisis. Despite the enormous literature of the question, [ 14 ] the theoretical understanding of critical situations is rather poorly developed. This is especially true of the theories of stress and crisis, where many authors confine themselves to simply listing specific events that result in stress or crisis situations, or use general schemes such as an imbalance (mental, mental, emotional) to characterize these situations. without specifying. Despite the fact that the themes of frustration and conflict, each separately, are worked out much better, it is not possible to establish clear relations between these two concepts (185), not to mention the complete absence of attempts to correlate all four of these concepts at the same time, to establish, not to overlap whether they are, what are the logical conditions for the use of each of them, etc. The situation is such that the researchers who study one of these topics put any critical situation into a favorite category, so for the psychoanalyst any such situation is a conflict situation, for the followers of G. Selye a stress situation, etc., and the authors whose Interests are not specifically related to this issue, when choosing the concept of stress, conflict, frustration or crisis come mainly from intuitive or stylistic considerations. All this leads to a lot of terminological confusion.

In view of this position, the primary theoretical task, which will be solved on the following pages, is the allocation of a specific categorical field for each of the conceptual fixations of the critical situation, defining its scope, application. Solving this problem, we will proceed from the general idea, according to which the type of critical situation is determined by the nature of the state of "impossibility" in which the subject’s livelihoods find themselves. This “impossibility” is determined, in turn, by what vital need is paralyzed as a result of the inability of the types of activity available to the subject to cope with the available external and internal conditions of life activity. These external and internal conditions, the type of activity and the specific vital need are the main points by which we will characterize the main types of critical situations and distinguish them from each other.

Stress

The lack of clarity of categorical grounds and limitations has most affected the concept of stress. Meaning first the nonspecific response of the body to the effects of harmful agents, manifested in the symptoms of the general adaptation syndrome (132; 133), this concept is now attributed to anything, so that in the critical work on stress there was even a peculiar genre tradition to begin a review of research by enumerating by miracle coexist under the cap of this concept of such completely heterogeneous phenomena as a reaction to cold influences and criticism heard, hyperventilation of the lungs in conditions of forced respiration and the joy of success, fatigue and humiliation (43; 81; 106; 164 and others). According to R. Luft, “many consider stress what happens to a person if he is not lying on his bed” (163, p.317), and G. Selye believes that “a person who is sleeping can experience some stress "(133, p.30), and equates the absence of stress to death (ibid.). If we add to this that stressful reactions are inherent, according to Selye, to all living things, including plants, then this concept, along with its simple derivatives (stressor, micro- and macrostress, good and bad stress) becomes the center of to their claims of the system, suddenly gaining dignity no more and no less than “the leading stimulus of life-affirmation, creation, development” (147, p.7), “the foundations of all aspects of human activity” (ibid., p. 14) or foundation for homegrown philosophical and ethical pic swarming (133).

Such transformations of a concrete scientific concept into a universal principle are so familiar from the history of psychology, Vygotsky (47) describes the regularities of this process in such a way that the state in which the analyzed concept now lies can probably be predicted at the very beginning of the "stress boom" : "This discovery, swelling up to the worldview, is like a frog, swollen in an ox, this wimp in a nobility gets into the most dangerous ... stage of its development: it easily bursts like a soap bubble; (15) in any case, it enters stage of struggle and denial that it now meets on all sides "(47, s.304).

In fact, in modern psychological work on stress, persistent attempts are made in one way or another to limit the claims of this concept, subjecting it to traditional psychological problems and terminology. R. Lazarus with this purpose introduces the idea of psychological stress, which, unlike the physiological highly stereotyped stress response to harm, is a reaction mediated by the threat assessment and protective processes (81; 214). J. Averill, following S.Sells, (239) considers the essence of a stressful situation to be loss of control, i.e. the lack of an adequate response to this situation, with the significance for the individual of the consequences of not responding (172, p. 286). P. Fress suggests calling a special kind of emotiogenic situations stress, namely “to use this term in relation to situations that are repetitive, or chronic, in which adaptation disorders may appear” (158, p. 145). Yu. S. Savenko defines mental stress as "a state in which a person finds himself in conditions that prevent his self-actualization" (130, p.97).

This list could be continued, but the main trend in the development of the concept of stress by psychology is also evident from these examples. It consists in denying non-specific situations that generate stress. Not any requirement of the environment causes stress, but only that which is assessed as threatening (81; 214), which violates adaptation (158), control (172), prevents self-actualization (130). “Hardly anyone thinks,” R. S. Razumov appeals to common sense, “that any muscle tension should be a stressful agent for the body. A quiet walk ... no one perceives as a stressful situation” (118, p.16) .

However, none other than the father of stress teaching, Hans Selye himself, even considers the state of sleep, not to mention a walk, to be stress free. Stress, according to G. Selye, is a non-specific response of the organism to any (we emphasize: any. - F.V. ) the demand presented to him "(133, p.27).

The reaction of psychologists can be understood: indeed, how to reconcile this formulation with the ineradicable notion of stress that stress is something unusual, out of the ordinary, exceeding the limits of the individual norm of functioning? How to combine in one thought "any" with "extreme"? It would seem that this is impossible, and psychologists (and physiologists (164, pp. 12-16)) discard "any", i.e. the idea of non-specific stress, opposing the idea of specificity. But to eliminate the idea of non-specific stress (situations and reactions) is to kill in this concept what it was created for, its main meaning. The pathos of this concept is not in the denial of the specific nature of the stimuli and the body’s responses to them (133, pp. 27-28; 240, p.12), but in the statement that any stimulus, along with its specific action, imposes on the body, non-specific requirements, the answer which is a nonspecific reaction in the internal environment of the body.

It follows from the above that if psychology adopts the concept of "stress", then its task is to refuse the unreasonable expansion of the scope of this concept, nevertheless, to preserve its main content - the idea of non-specific stress. To solve this problem, it is necessary to explicate those conceivable psychological conditions under which this idea accurately reflects the slice of psychological reality set by them. We are talking about accuracy, that's why. No doubt, violations of self-actualization, control, etc. cause stress, these are sufficient conditions for it. But the point is to find the minimum necessary conditions, more precisely, the specific conditions for generating a non-specific formation - stress.

Any requirement of the environment can cause a critical, extreme situation only for a creature that is unable to cope with any demands at all and at the same time the inner necessity of life of which is the urgent (here-and-now) satisfaction of every need, in other words, for a creature the normal life world of which is "easy" and "simple", i.e. such that the satisfaction of any need occurs directly and directly, without encountering obstacles from either external forces or other needs and, therefore, not demanding any activity from the individual.

The full realization of such a hypothetical existence, when the benefits are given directly and directly and the whole life is reduced to immediate vitality, can be seen, and even with certain reservations, only in the stay of the fetus in the womb, but in part it is inherent in all life, manifesting itself as here-and-now satisfaction, or in what Z. Freud called the "pleasure principle."

It is clear that the implementation of such an installation quite often breaks through with the most ordinary, any requirements of reality; and if such a breakthrough is qualified as a special critical situation - stress, we come to the notion of stress, in which it is possible to combine the idea of "extremality" and the idea of "non-specificity" in an obvious way. Under the described substantive-logical conditions, it is quite clear how stress can be considered a critical event and at the same time to consider it as a permanent vital condition.

So, the categorical field, which is behind the concept of stress, can be denoted by the term “vitality”, meaning by it the ineradicable dimension of being, the “law” of which is the installation on here-and-now satisfaction.

Frustration

The necessary signs of a frustrating situation according to most definitions are the presence of a strong motivation to achieve the goal (to satisfy the need) and the obstacles hindering this achievement (107; 199; 208; 210; 215; 236, etc.).

In accordance with this, frustrating situations are classified according to the nature of the frustrated motifs and the nature of the "barriers". Classifications of the first kind include, for example, A. Maslow (223 )’s distinction between basic, “inborn” psychological needs (for security, respect and love), the frustration of which is pathogenic, and “acquired need”, the frustration of which does not cause mental disorders .

Barriers that block an individual's path to a goal can be physical (for example, prison walls), biological (illness, aging), psychological (fear, intellectual inadequacy) and sociocultural (norms, rules, prohibitions) (199; 210). We also mention the division of barriers into external and internal, used by T. Dembo (183) to describe her experiments: she called internal barriers those that impede the achievement of a goal, and external barriers those that do not allow subjects to get out of the situation. K. Levin, analyzing the external barriers used by adults to control the child’s behavior, distinguishes between "physical and material" and "sociological" ("tools of power that an adult has because of his social position" (215, p.126)) and “ideological” barriers (a kind of social, characterized by the inclusion of “goals and values recognized by the child himself” (ibid., p.127). Illustration: “Remember, you're a girl!”).

The combination of strong motivation to achieve a certain goal and obstacles to it, of course, is a necessary condition for frustration, but sometimes we overcome significant difficulties without falling into a state of frustration. This means that the question of sufficient conditions for frustration must be raised, or, equivalently, the question of the transition of a situation of difficulty in activity to a situation of frustration (cf. 83). It is natural to look for the answer to it in the characteristics of the state of frustration, because its presence distinguishes the situation of frustration from the situation of difficulty. However, in the literature on the problem of frustration, we do not find an analysis of the psychological meaning of this state; most authors confine themselves to descriptive statements that a person, being frustrated, is anxious and stressed (199), feelings of indifference, apathy and loss of interest (236), guilt and alarm ( 210), rage and hostility (199), envy and jealousy (192), etc. By themselves, these emotions do not clarify our question, and besides them we still have the only source of information - behavioral "consequences" of frustration, or frustration behavior. Perhaps the peculiarities of this behavior can shed light on what happens during the transition from a situation of difficulty to a situation of frustration?

The following types of frustration behavior are usually distinguished: a) motor arousal — aimless and disordered reactions; b) apathy (in the well-known study of R. Barker, T. Dembo and K. Levin (173) one of the children in a frustrating situation lay down on the floor and looked at the ceiling); c) aggression and destruction ; d) stereotype - a tendency to blindly repeat fixed behavior; e) regression , which is understood either as “an appeal to behavioral models that dominated the earlier periods of an individual’s life” (236, pp.246-247), or as “primitivization” of behavior (measured in the experiment of R. Barker, T. Dembo and K. Levin's decline in "constructive" behavior) or a drop in the "quality of performance" (180).

These are the types of frustration behavior. What are its most significant, central characteristics? The monograph by N. Mayer (220) answers this question with its own name - “Frustration: Behavior Without Goal”. In another paper, N. Mayer (221) explained that the basic statement of his theory is not that “a frustrated person has no goal”, but “that the behavior of a frustrated person does not have a goal, that is, it loses its target orientation” (221, p. 370-371). Meyer illustrates his thesis with an example in which two people hurrying to buy a train ticket start a quarrel in a queue, then a fight, and both of them are late in the end. This behavior does not contain the goal of getting the ticket, therefore, according to Mayer’s definition, it is not adaptive (= satisfying need), but “frustratedly provoked behavior”. The new goal does not replace the old one (ibid.).

To clarify the position of this author, you need to set it apart with other opinions. Thus, E. Fromm believes that frustration behavior (in particular, aggression) "represents an attempt, although often useless, to achieve a frustrated goal" (192, p.20). K. Goldstein, on the contrary, argues that the behavior of this kind is not subordinated not only to the frustrated goal, but to no goal at all, it is disorganized and disorderly. He calls this behavior "catastrophic" (194).

Against this background, N. Meyer’s point of view can be formulated as follows: a necessary sign of frustration behavior is a loss of focus on the original, frustrated goal (as opposed to E. Fromm's opinion), the same sign is sufficient (as opposed to K. Goldstein) - frustration behavior is not necessarily devoid of any purposefulness, inside it may contain some goal (for example, it is more painful to hurt an opponent in a frustration-provoked quarrel). It is important that the achievement of this goal is meaningless relative to the original goal or motive of the situation.

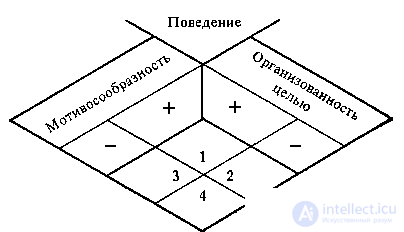

The differences of these authors help us to identify two most important parameters by which behavior in a frustrating situation should be characterized. The first of them, which can be called "motive", is the presence of a meaningful perspective connection of behavior with a motive constituting a psychological situation. The second parameter is the organization of behavior for any purpose, regardless of whether the achievement of this goal leads to the realization of this motive. Assuming that both parameters of behavior may in each case have a positive or negative value, i.e. that the current behavior can be either ordered and organized by the goal, or disorganized, and at the same time it can be either a suitable motive or not, we get the following typology of possible “states” of behavior.

Typology of "states" of behavior

In a situation that is difficult for the subject, we can observe behaviors corresponding to each of these four types.

Поведение первого типа, мотивосообразное и подчиненное организующей цели, заведомо не является фрустрационным. Причем здесь важны именно эти внутренние его характеристики, ибо сам по себе внешний вид поведения (будь то наблюдаемое безразличие субъекта к только что манившей его цели, деструктивные действия или агрессия) не может однозначно свидетельствовать о наличии у субъекта состояния фрустрации: ведь мы можем иметь дело с произвольным использованием той же агрессии (или любых других, обычно автоматически относящихся к фрустрационному поведению актов), использованием, сопровождающимся, как правило, самоэкзальтацией с разыгрыванием соответствующего эмоционального состояния (ярости) и исходящим из сознательного расчета таким путем достичь цели.

Такое псевдофрустрационное поведение может перейти в форму поведения второго типа: умышленно "закатив истерику" в надежде добиться своего, человек теряет контроль над своим поведением, он уже не волен остановиться, вообще регулировать свои действия. Произвольность, т.е. контроль со стороны воли, утрачен, однако это не значит, что полностью утрачен контроль со стороны сознания. Поскольку это поведение более не организуется целью, оно теряет психологический статус целенаправленного действия , но тем не менее сохраняет еще статус средства реализации исходного мотива ситуации, иначе говоря, в сознании сохраняется смысловая связь между поведением и мотивом, надежда на разрешение ситуации. Хорошей иллюстрацией этого типа поведения могут служить рентные истерические реакции, которые образовались в результате "добровольного усиления рефлексов" (79, с.72), но впоследствии стали непроизвольными. При этом, как показывают, например, наблюдения военных врачей, солдаты, страдавшие истерическими гиперкинезами, хорошо осознавали связь усиленного дрожания с возможностью избежать возвращения на поле боя.

Для поведения третьего тира характерна как раз утрата связи, через которую от мотива передается действию смысл. Человек лишается сознательного контроля над связью своего поведения с исходным мотивом: хотя отдельные действия его остаются еще целенаправленными, он действует уже не "ради чего-то", а "вследствие чего– то". Таково упоминавшееся поведение человека, целенаправленно дерущегося у кассы со своим конкурентом в то время, как поезд отходит от станции. "Мотивация здесь, – говорит Н. Майер, – отделяется от причинения как объясняющее понятие" (221, с.371; ср.:142, с.101).

Поведение четвертого типа, пользуясь термином К. Гольдштейна, можно назвать "катастрофическим". Это поведение не контролируется ни волей, ни сознанием субъекта, оно и дезорганизовано, и не стоит в содержательно-смысловой связи с мотивом ситуации. Последнее, важно заметить, не означает, что прерваны и другие возможные виды связей между мотивом и поведением (в первую очередь "энергетические"), поскольку, будь это так, не было бы никаких оснований рассматривать это поведение в отношении фрустрированного мотива и квалифицировать как "мотивонесообразное". Предположение, что психологическая ситуация продолжает определяться фрустрированным мотивом, является необходимым условием рассмотрения поведения как следствия фрустрации.

Возвращаясь теперь к поставленному выше вопросу о различении ситуации затрудненности и ситуации фрустрации, можно сказать, что первой из них соответствует поведение первого типа нашей типологии, а второй – остальных трех типов. С этой точки зрения видна неадекватность линейных представлений о фрустрационной толерантности, с помощью которых обычно описывается переход ситуации затрудненности в ситуацию фрустрации. На деле он осуществляется в двух измерениях – по линии утраты контроля со стороны воли, т.е. дезорганизации поведения и/или по линии утраты контроля со стороны сознания, т.е. утраты "мотивосообразности" поведения, что на уровне внутренних состояний выражается соответственно в потере терпения и надежды. Мы ограничимся пока этой формулой, ниже нам еще представится случай остановиться на отношениях между этими двумя феноменами.

Определение категориального поля понятия фрустрации не составляет труда. Вполне очевидно, что оно задается категорией деятельности. Это поле может быть изображено как жизненный мир, главной характеристикой условий существования в котором является трудность, а внутренней необходимостью этого существования – реализация мотива. Деятельное преодоление трудностей на пути к "мотивосообразным" целям – "норма" такой жизни, а специфическая для него критическая ситуация возникает, когда трудность становится непреодолимой (83, с.119, 120), т.е. переходит в невозможность.

Конфликт

Задача определения психологического понятия конфликта довольно сложна. Если задаться целью найти дефиницию, которая не противоречила бы ни одному из имеющихся взглядов на конфликт, она звучала бы психологически абсолютно бессодержательно: конфликт – это столкновение чего-то с чем-то. Два основных вопроса теории конфликта – что именно сталкивается в нем и каков характер этого столкновения – решаются совершенно по-разному у разных авторов.

Решение первого из этих вопросов тесно связано с общей методологической ориентацией исследователя. Приверженцы психодинамических концептуальных схем определяют конфликт как одновременную актуализацию двух или более мотивов (побуждений) (205; 210). Бихевиористски ориентированные исследователи утверждают, что о конфликте можно говорить только тогда, когда имеются альтернативные возможности реагирования (160; 185). Наконец, с точки зрения когнитивной психологии в конфликте сталкиваются идеи, желания, цели, ценности – словом, феномены сознания (146; 181; 187). Эти три парадигмы рассмотрения конфликта сливаются у отдельных авторов в компромиссные "синтагматические" конструкции (см., например, (236)), и если конкретные воплощения таких сочетаний чаще всего оказываются эклектическими, то сама идея подобного синтеза выглядит очень перспективной: в самом деле, ведь за тремя названными парадигмами легко угадываются три фундаментальные для развития современной психологии категории – мотив, действие и образ (168), которые в идеале должны органически сочетаться в каждой конкретной теоретической конструкции.

Не менее важным является и второй вопрос – о характере отношений конфликтующих сторон. Он распадается на три подвопроса, первый из которых касается сравнительной интенсивности противостоящих в конфликте сил и разрешается чаще всего утверждением о приблизительном равенстве этих сил (215; 219; 226 и др.). Второй подвопрос связан с определением ориентированности друг относительно друга противоборствующих тенденций. Большинство авторов даже не обсуждает альтернатив обычной трактовке конфликтующих побуждений как противоположно направленных. К. Хорни проблематизировала это представление, высказав интересную идею, что только невротический конфликт (т.е. такой, который, по ее определению, отличается несовместимостью конфликтующих сторон, навязчивым и бессознательным характером побуждений) может рассматриваться как результат столкновения противоположно направленных сил. "Угол" между направлениями побуждений в нормальном, не невротическом конфликте меньше 180°, и потому при известных условиях может быть найдено поведение, в большей или меньшей мере удовлетворяющее обоим побуждениям (205).

Третий подвопрос касается содержания отношений между конфликтующими тенденциями. Здесь, по нашему мнению, следует различать два основных вида конфликтов – в одном случае тенденции внутренне противоположны, т.е. противоречат друг другу по содержанию, в другом – они несовместимы не принципиально, а лишь по условиям места и времени.

Для выяснения категориального основания понятия конфликта следует вспомнить, что онтогенетически конфликт – достаточно позднее образование (232). Р. Спиц (246) полагает, что действительный интрапсихический конфликт возникает только с появлением "идеационных" понятий. К. Хорни (205) в качестве необходимых условий конфликта называет осознание своих чувств и наличие внутренней системы ценностей, а Д. Миллер и Г. Свэнсон – "способность чувствовать себя виновным за те или иные импульсы" (226, с.14). Все это доказывает, что конфликт возможен только при наличии у индивида сложного внутреннего мира и актуализации этой сложности.

Здесь проходит теоретическая граница между ситуациями фрустрации и конфликта. Ситуация фрустрации, как мы видели, может создаваться не только материальными преградами, но и преградами идеальными, например, запретом на осуществление некоторой деятельности. Эти преграды, и запрет в частности, когда они выступают для сознания субъекта как нечто самоочевидное и, так сказать, не обсуждаемое, являются по существу психологически внешними барьерами и порождают ситуацию фрустрации, а не конфликта, несмотря на то, что при этом сталкиваются две, казалось бы, внутренние силы. Запрет может перестать быть самоочевидным, стать внутренне проблематичным, и тогда ситуация фрустрации преобразуется в конфликтную ситуацию.

Just as the difficulties of the external world are opposed to activity, so are the complexities of the internal world, i.e. overlapping of life relations of the subject, opposes the activity of consciousness. The inner necessity , or the aspiration of the activity of consciousness, consists in achieving the coherence and consistency of the inner world. Consciousness is designed to measure motives, to choose between them, to find compromise solutions, etc., in a word, to overcome complexity. The critical situation here is such that it is subjectively impossible to either get out of the conflict situation, nor resolve it by finding a compromise between conflicting motivations or sacrificing one of them.

Just as above we distinguished the situation of the difficulty of activity and the impossibility of its realization, we must distinguish between the situation of complication and the critical conflict situation that occurs when consciousness capitulates to the subjectively insoluble contradiction of motives.

A crisis

Although the problem of the crisis of individual life has always been in the field of attention of humanitarian thinking, including psychological (see, for example, (62)), as an independent discipline developed mainly in the framework of preventive psychiatry, the theory of crises appeared on the psychological horizon relatively recently . Its beginning is taken from the remarkable article by E. Lindemann (217), devoted to the analysis of acute grief.

"Historically, the theory of crises was mainly influenced by four intellectual movements: the theory of evolution and its applications to the problems of general and individual adaptation; the theory of achievement and growth of human motivation; an approach to human development from the point of view of life cycles and an interest in coping with extreme stresses ... "(228, p.7). Among the ideological origins of the theory of crises are also called psychoanalysis (and, above all, such concepts as mental balance and psychological defense), some of the ideas of C. Rogers and the theory of roles (206, p.815).

Distinctive features of the theory of crises, according to J. Jacobson, are as follows:

As for the specific theoretical principles of this discipline, they basically reproduce what we already know from the theories of other types of critical situations. Among empirical events that can lead to a crisis, various authors point out such as the death of a loved one, serious illness, separation from parents, family, friends, appearance changes, change of social situation, marriage, drastic changes in social status, etc. (135; 178; 182; 195; 202; 217, etc.). Theoretically, life events qualify as leading to a crisis if they "create a potential or actual threat to the satisfaction of fundamental needs ..." (206, p. 816) and at the same time pose a problem to an individual, "from which he cannot escape and which cannot allow in a short time and in the usual way "(178, p.525).

J. Kaplan (178) described four successive stages of the crisis: 1) primary stress increase, stimulating the usual ways of solving problems; 2) further increase in voltage in conditions where these methods are unsuccessful; 3) an even greater increase in voltage, requiring the mobilization of external and internal sources; 4) if everything turns out to be in vain, the fourth stage begins, characterized by increased anxiety and depression, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, and disorganization of the personality. A crisis can end at any stage if the danger disappears or a solution is found.

The concept of crises owes its relative autonomy not so much to its own theoretical features as to the fact that it is an integral part of the rapidly developing in many countries practice of short-term and accessible to wide sections of the population (as opposed to expensive psychoanalysis) psychological and psychiatric assistance to a person in a critical situation. This concept is inseparable from the service of mental health, crisis-prevention programs, etc., which explains both its obvious advantages - direct interchange with practice, the clinical concreteness of the concepts, and equally obvious shortcomings - eclecticism, lack of development of its own system of categories and lack of clarity used concepts with academic psychological representations.

Therefore, it is too early to talk about the psychological theory of crises in the true sense of the word. However, we take the liberty to assert that the category-forming category of this future concept (if it is destined to happen) should be the category of individual life, understood as a developing whole, as the life course of an individual. In fact, a crisis is a crisis of life , a critical moment and a turning point in the path of life.

The inner necessity of the life of the individual is the realization of his own way, his life plan. The psychological “organ” that conducts design through the inevitable difficulties and complexities of the world is will . Will is an instrument for overcoming the forces of difficulty and complexity “multiplied” against each other. When in the face of events covering the most important life relationships of a person, the will turns out to be powerless (not at this isolated moment, but in principle, in the perspective of realizing the life plan), a critical situation specific to this plane of vital activity arises - a crisis.

As in the cases of frustration and conflict, we can distinguish two kinds of crisis situations, differing in the degree they leave the possibility of realizing the inner necessity of life. The crisis of the first kind can seriously complicate and complicate the realization of the life plan, but it still remains possible to restore the course of life interrupted by the crisis. This is a test from which a person can emerge who have retained in a substantial life purpose and who have certified their self-identity. The situation of the second kind, the crisis itself, makes the realization of the life plan impossible. The result, the experience of this impossibility - the metamorphosis of the personality, its rebirth, the adoption of a new plan of life, new values, a new life strategy, a new image-I.

So, each of the concepts fixing the idea of a critical situation corresponds to a special categorical field setting the norms for the functioning of this concept, which must be taken into account for its critical use. Such a categorical field in terms of ontology reflects a particular dimension of human life activity, which has its own laws and is characterized by inherent conditions of life activity, type of activity and specific internal necessity. We summarize all these characteristics in the table. one.

Table 1

Typology of critical situations

Ontological field | Type of activity | Internal need | Normal conditions | Type of emergency |

"Vitality" | Vital activity of the body | Here-and-now satisfaction | Immediate Giving of Life Goods | Stress |

Separate life relation | Activity | Implementation of motive | Difficulty | Frustration |

Inner world | Consciousness | Internal consistency | Complexity | Conflict |

Life as a whole | Will | Realization of life intent | Difficulty and difficulty | A crisis |

What is the significance of these distinctions for analyzing critical situations and for the theory of experience in general? This typology enables more differentiation to describe extreme life situations.

Of course, a specific event can immediately affect all the “dimensions” of life, simultaneously causing stress, frustration, conflict, and crisis, but it is this empirical interference of different critical situations that makes it necessary to strictly distinguish them.

A specific critical situation is not a frozen formation, it has a complex internal dynamics, in which various types of situations of impossibility interfere with each other through internal states, external behavior and its objective consequences. For example, difficulties in trying to achieve a certain goal due to prolonged dissatisfaction with the need may cause an increase in stress, which, in turn, will negatively affect the activity and lead to frustration; then aggressive impulses or reactions generated by frustration may conflict with the moral attitudes of the subject, conflict will again cause an increase in stress, etc. The main problematic nature of a critical situation may shift from one “dimension” to another.

In addition, since the emergence of a critical situation, the psychological struggle with the experiencing processes begins, and the overall picture of the dynamics of the critical situation is further complicated by these processes, which can, being beneficial in one dimension, only worsen the situation in the other. However, this is the topic of the next section.

It remains to emphasize the practical importance of established conceptual distinctions. They contribute to a more accurate description of the nature of the critical situation in which the person finds himself, and this largely determines the correct choice of the strategy for psychological assistance.

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of experience

Terms: Psychology of experience