Lecture

It is sometimes better to ask questions than to know in advance all the answers. (J. Terber)

What is the question - is the answer. (Popular wisdom)

Zagashev Igor, psychologist, teacher of psychology, deputy director of the Pedagogical College No. 1 named after. N. A. Nekrasova, St. Petersburg.

Source: Zagashev I. New pedagogical technologies in the school library: educational technology for the development of critical thinking by means of reading and writing // Library in school. 2004, No. 18 (or: Zagashev I. Ability to ask questions. // Peremena, spring 2001 (4). - P. 8–13).

The question mark is shaped like a fishing hook. Anyone knows that you can catch fish with it. But does everyone succeed? If someone doubts that the ability to ask questions requires additional development, ask him about the task of John and Bill. When I offer it to my students who attend the “Development of the Intellect” course, those who are the best at asking questions can cope with it most quickly.

Ask the interviewee to write down the condition of the problem verbatim: John and Bill were in the room. Slammed the door. There was a sound of broken glass. John looked at Bill. Bill was dead. Why did Bill sleep? In order to find a solution, it is allowed to ask any questions, except for the main task, which appears at the end of the text. The moderator answers them honestly, but not deployed. Someone from the students will begin to guess, someone will begin to recall similar situations from films. But the winner is the one who is the best at asking questions! (For those who do not know the answer - the content of the first paragraph of the article contains a hint. Those who are not helped by the hint will probably be helped by the content of the article. The impatient can immediately look at the end).

I was not at all surprised by the following fact. In the pedagogical college where I work, the teachers decided to purposefully develop students' research skills (the ability to plan research, record information, highlight the main and secondary, etc.). At one of the seminars, it was discussed which of the indicated skills should be developed first of all. Colleagues were faced with the task of ranking more than twenty different skills, abilities and other characteristics. Overwhelmingly, priority was given to the ability to ask questions. The teachers argued their opinion: “The questions of the students are often monosyllabic and are associated only with the factual side of the material”, “They are used to the questions of reproduction”. The results of psychological and pedagogical research confirmed that teachers are not satisfied with the level at which students formulate questions. Do you need this skill at all?

Psychologist V. M. Snetkov describes the communicative value of a question as “a set of possible alternatives to the answers allowed by this question” (Snetkov VM, 1999, p. 92). Consequently, a “good question” is one that allows a sufficiently large space of possible alternatives . The same author identifies several functions of the questions: getting new information, clarifying the existing one, transferring the conversation to another topic, prompting the answer, demonstrating one's opinion, assessment, position; tuning the mind and emotions of the interlocutor in a certain way. (Snetkov V.M., 1999, p. 93).

“To live is to have problems, and to solve them is to grow intellectually,” wrote intelligence researcher J. Guilford. “The question is, according to the opinion of the professor of psychology L.M. Vekker - there is a mental reflection of the unrevealed, unrepresentation of those objective relations, the elucidation of which is followed by the entire subsequent thought process (Vekker LM, 1998, p. 6). Consequently, the question “launches” cognitive activity aimed at solving a certain problem, removing some uncertainty. But the question also contributes to determine, formulate the problem .

Through questions, man bridges the unknown. This unknown can look attractive, and can sometimes frighten. Apparently, it is not for nothing that the English word “question” (which means “question”) comes from the word “quest”, which may mean “searches associated with some uncertainty and even risk”. The very origin of the word “question” (at least in English) implies the presence of a search in a situation of uncertainty. And since uncertainty is an integral feature of the modern rapidly changing world, the development of the ability to ask questions is extremely important.

In the words of Alison King, “thinkers know how to ask questions” (King, 1994, p. 18). Some teachers determine how much their students can think by the way they formulate questions. King conducted a series of studies and concluded that the ability to ask thoughtful questions is a skill that should be taught, since most people are used to asking rather primitive questions that require only a small memory stress when answering them (quoted in Halpern D., 2000 , p. 139).

If a person learns and does not ask questions (meaning his own, independently formulated), he does not experience a state of incompleteness, which is the basis for any cognitive activity. Having formulated a question, we take responsibility for the state of cognitive “hunger”, the cause of which it is.

So, questions are needed in order to navigate the world around us, and those who can ask them are better oriented than those who do not know how.

Unfortunately, one cannot but agree with Rosemary Smid, who wrote that “ordinary school practice forms expectations among children, that there is a“ right answer ”to any question and (...) if they are sufficiently prepared or smart, they can always find it. "(Smid, R., 1999, p. 149). That is why the situation when a student, a student cannot answer a question (even if he formulated this question himself), is unpleasant, causes a desire to protect oneself. We should not forget how difficult it is to get rid of already formed ideas. Therefore, we propose to start collecting the conditions necessary for the successful development of the ability to ask questions.

The situation where the student can not answer the question, the teacher should be considered normal . If it is not about tests or traditional tests, the fact of difficulty should be taken as ordinary. “We are constantly faced with difficulties. We are learning to overcome them. ”

The teacher should use more open, creative questions that can be presented with several answers and that encourage further dialogue.

R. Smid recommends more often to use the “questions of Colombo” (on behalf of the famous television detective story), beginning with the words: “ Oh, by the way, it’s interesting ... ” and addressed to no one (Smid R., 1999, p. 149). The teacher in the form of a question shares her difficulty in the presence of children. One condition is that this difficulty must be real, not “playful,” since “staging” rarely gives the expected result.

It should not be a matter of forcing children to defend themselves . With the appropriate intonation, any question that begins with the word “why” is perceived as a desire to put the student in a situation justifying.

Students must have a choice and they create this choice themselves . The teacher organizes the work in such a way that the students, students can create a "bank" of questions, which then determines the search area, the direction in studying the material.

For several years, my professional interests have been closely associated with the development of the thinking of students of all ages. The following are some strategies and techniques that have helped many teachers develop their students' ability to ask questions.

This strategy is used when students already have some information on the topic and are guided in a number of basic concepts related to the material being studied. "Question words" help them create a so-called "field of interest."

The teacher asks students to recall various concepts related to the topic and write them in the right-hand column of a two-part table. In the left part, students write down various interrogative words (no less than 8–10). After that, it is proposed to formulate as many questions as possible in 5-7 minutes, combining elements of both columns. This work can be done individually or in pairs.

One condition! Students should not know the answers to their questions. Why ask if the answer is known !? Thus, there will be several lists of various questions. For example:

Course: "Pedagogical Psychology".

Audience: 5th year students of the pedagogical college.

Theme: "Pedagogical conflict."

Objectives: (1) Independent determination by students of those parties to a pedagogical conflict that require studying in the first place. Since in education (as in other areas) conflict is a common occurrence, for subsequent work it is necessary to determine which issues for this audience are most relevant. (2) The development of the ability to ask questions.

Lesson progress:

1. Students were given homework to remember and write down one or two situations of pedagogical conflict, the causes of which are not clear.

2. After discussing such situations in groups (10 min.), Students write out the basic terms and concepts that they used in the right side of the table.

Question words | Basic concepts of the topic |

How? | Unwarranted expectations |

What? | Anger |

Where? | Emotions "over the edge" |

Why? | Misunderstanding |

How many? | The end of the relationship |

From where | Stress relief |

Which one | Bad behavior |

What for? | Conflict |

How? | pupils |

What is the relationship? | The teachers |

What is it made of? | Reconciliation |

What is the purpose? |

Examples of questions: “Why do teachers start a conflict most often?”, “How long does it take to settle a conflict?”

Then we ask students to discuss their lists and select two (3-4) most interesting (productive, unexpected, insightful, etc.) questions. Before students read the results of their work to the whole group / class, they are invited to think about the criteria they have made. Not everyone will immediately give a reasoned answers. Some will say: "Just liked and everything." In this case, the teacher can write down questions that the students could not justify in order to return to them in the future.

If the teacher conducts this activity at the end of the lesson, the next meeting can be planned based on the questions of the students. If he pre-examines the material in this activity, it is possible to organize purposeful work with information so that students look for answers to their questions.

The teacher may experience some confusion due to the large number of questions of a too general plan or because of an excess of questions that he is not ready (or did not plan) to answer in this lesson. These “unanswered questions” can be periodically returned as the material is further studied. One way or another, the teacher has the opportunity to obtain objective data on topics that are most interesting for students (they are usually the most specifically formulated and often repeated in questions).

Just look at this table to understand the essence of this technique.

? | ? |

In this column we write down those questions to which a detailed, “long”, detailed answer is expected. For example, “what is the relationship between time of year and human behavior?”. | In this column, we write down questions that are supposed to unambiguous, "actual" answer. For example, "what time is it?" |

The technique “Thick and Thin Questions” is known and used in the following training situations:

For the organization of interrogation . After studying the topic, students are asked to formulate three “thin” and three “thick” questions related to the material studied. Then they interrogate each other using their tables.

To start a conversation on the topic being studied . If you simply ask: “What are you interested in in this topic?”, It is likely that the questions will turn out to be rash and precocious. If, after a short introduction, to ask students to formulate at least one question in each column, then it is already possible to judge the main directions of studying the topics that interest the students.

To identify unanswered questions after studying the topic. Often, students ask questions without taking into account the time it takes to answer. Teachers may call such questions inappropriate and untimely. The described technique develops the ability to assess the relevance of a particular issue, at least by time parameter.

Remember the "harmful" children's game "Buy elephant"? Recall. One child comes up to another and says: “Buy an elephant!”. He replies: "I do not need any elephant!". And the first one objects: “Everyone says: I don’t need any elephant! and you buy an elephant! ”. This dialogue can last indefinitely. In addition to endurance and patience, he apparently develops the ability to find such a verbal construct that allows you to successfully get out of a difficult situation. Something like this game is similar to the reception of 6 "W". “W” is the first letter of the question word “Why?”, Which translates from English not only as “Why?”, But also as “Why?”, “For what reason?”, Etc.

Let's give an example. A teacher of educational psychology after studying the topic “Motivation for learning activities” asks students to split into pairs. There is such a dialogue between students. The first one asks: “Why study the topic Motivation for learning activities ?”. The second replies: "To know the different ways of awakening this motivation in the learning process." The first is not appealing: "Why do you need to know the various ways to awaken motivation in the educational process?". The second "gets out": "In order for the children to be more interested in studying my subject." "Why do you want children to be interested in studying your subject?". And so on.

Thanks to this technique, students not only have the opportunity to establish many connections within a single topic (and, as is well known, knowledge that has many different connections is the most durable), not only are aware of deeper reasons for studying this concept, but also determine for themselves personal the meaning of his study. They are like “grounding” “dry” information to a vital, practical, level. As a result, they “feel the ground under their feet,” gain self-confidence.

Reception "6 W" allows you to learn how to formulate a question in order to determine an unknown area within the framework of a seemingly fully studied topic. All questions and answers should be recorded. One condition - the answers should not be repeated.

Sometimes it happens that students can not answer the question and irritably say: "Why, why ... Yes, because!". For such cases there is a special rubric "Because!", Where the questions causing the desire to respond sharply are recorded. It seems to be a trifle, but with its introduction, communication between students began to take place in an even more benevolent atmosphere, and the “Because” column is rarely filled. What do you think, what is the reason?

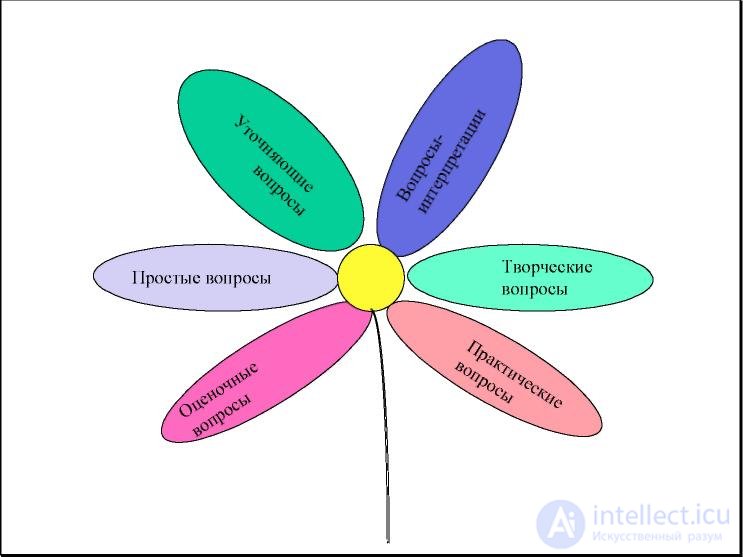

The taxonomy of questions, based on the taxonomy of educational objectives created by the famous American psychologist and teacher Benjamin Bloom on the levels of cognitive activity (knowledge, understanding, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation), is quite popular in the world of modern education. (Shishov S. E., Kalnei VA, 1999, p. 93). At the beginning of the study of the foundations of critical thinking, in the fall of 1997, we, considering that “Bloom” can be translated from German as “flower”, decided to make the theoretical constructions of the scientist more visual and attractive. Many of the participants in our seminars, practicing teachers, did not take the theory too well. We called the resulting “flower” the “Bloom Chamomile”. But disappointment awaited us: it was often difficult to clearly and unambiguously determine which type - according to B. Bloom's taxonomy - this or that question applies. In addition, many teachers said: "This is all beautiful, but active study of practical material is more useful for us."

The stage of modifications has begun: the wording of the questions was clarified, various ways of using the form of “chamomile” in the class were invented. As a result, we created “Chamomile Questions”, which in Russia is still stubbornly called “Bloom Chamomile”. The very list of questions on her petals was borrowed from the speeches of her American colleagues James and Carol Beers. It is appropriate to ask: "Who is the author of this reception?".

So six petals are six types of questions.

Simple questions - questions, answering which, you need to name some facts, recall and reproduce certain information. They are often used with traditional forms of control: on tests, in tests, when conducting terminological dictations, etc.

Clarifying questions . Usually they begin with the words: “So you say that ...?”, “If I understood correctly, then ...?”, “I could be wrong, but, in my opinion, did you say about ...?”. The purpose of these questions is to provide the person with opportunities for feedback on what he has just said. Sometimes they are asked to obtain information that is missing in the message, but implied. It is very important to ask these questions without negative facial expressions. As a parody of a clarifying question, we can give everyone a well-known example (raised eyebrows, wide eyes): “Do you really think that ...?”.

Интерпретационные (объясняющие) вопросы . Обычно начинаются со слова «Почему?». В некоторых ситуациях (об этом говорилось выше) они могут восприниматься негативно — как принуждение к оправданию. В других случаях они направлены на установление причинно-следственных связей. «Почему листья на деревьях осенью желтеют?». Если ответ на этот вопрос известен, он из интерпретационного «превращается» в простой. Следовательно, данный тип вопроса «срабатывает» тогда, когда в ответе присутствует элемент самостоятельности.

Творческие вопросы . Если в вопросе есть частица «бы», элементы условности, предположения, прогноза, мы называем его творческим. «Что изменилось бы в мире, будь у людей было не пять пальцев на каждой руке, а три?», «Как вы думаете, как будет развиваться сюжет фильма после рекламы?»

Оценочные вопросы . Эти вопросы направлены на выяснение критериев оценки тех или иных событий, явлений, фактов. «Почему что-то хорошо, а что-то плохо?», «Чем один урок отличается от другого?» и т.д.

Практические вопросы . Если вопрос направлен на установление взаимосвязи между теорией и практикой, мы называем его практическим. «Где вы в обычной жизни можете наблюдать диффузию?», «Как бы вы поступили на месте героя рассказа?».

Опыт использования этой стратегии показывает, что учащиеся всех возрастов (начиная с первого класса) понимают значение всех типов вопросов (то есть могут привести свои примеры).

Если мы используем «Ромашку вопросов» в младших классах, можно оставить визуальное оформление. Детям нравится формулировать вопросы по какой-либо теме, записывая их на соответствующие «лепестки». Работая с более старшим возрастом, можно оставить саму классификацию, тогда задание будет выглядеть следующим образом: «Перед тем, как читать текст о кактусах, самостоятельно сформулируйте по одному практическому и одному оценочному вопросу. Возможно, текст поможет нам на них ответить».

Как показывает практика ведения курсов повышения квалификации для преподавателей педагогических и непедагогических учебных заведений, педагогов, в основном, не смущает «детская» форма этой стратегии. Так, преподаватель курса «Речевая культура» педагогического колледжа № 1 Санкт-Петербурга, кандидат филологических наук А. Ю. Машковцева применила её для повторения материала. Студенты составляли вопросы, а затем сами искали на них ответы, используя различные источники информации. После этой работы преподаватель попросила их ответить на два вопроса: «Какие вопросы были наиболее сложными?» и «Насколько эта работа была для вас полезна?».

Вот основные результаты этого исследования.

Труднее всего учащимся даются творческие и практические вопросы. Все 68 опрошенных отметили, что работа была для них по-настоящему полезна, и аргументировали это тем, что формулируя вопросы, они лучше поняли и запомнили материал. Эти данные соответствуют результатам исследований, проведенных Палинсаром и Брауном (Palinsar & Brown, 1984), а также целым рядом других ученых. Так, Алисон Кинг, имя которой уже упоминалось в этой статье, обнаружила, что если студентам удается освоить технику использования (…) вопросов, они начинают задавать их в самых разнообразных ситуациях… (Халперн Д., 2000, с. 139).

Благодаря вопросам мы можем научиться лучше разбираться в ситуации и смотреть на неё под разными углами зрения. Именно это и нужно было сделать, чтобы решить задачку, предложенную уважаемым читателям в начале статьи.

Хотите узнать ответ? (Билл был рыбкой и погиб, когда банку сквозняком опрокинуло со стола)

Comments

To leave a comment

Interrogation: Questions as Tools for Thinking and Problem Solving

Terms: Interrogation: Questions as Tools for Thinking and Problem Solving